Crunching numbers second nature

A standout financial performance, constant and thorough planning, a strong partnership and off-farm fun all contribute to Wairarapa farmers Tim and Binds White’s farming success.

Award-winning farmer Tim White is always running numbers in his head and it shows in the performance of his family’s Matahiwi farm, just northwest of Masterton.

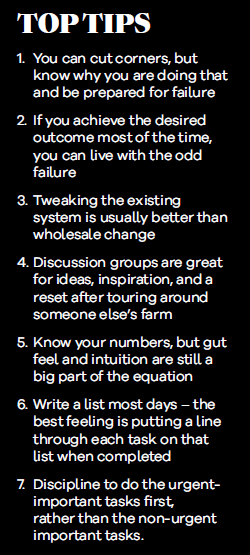

“I use lots of gut feel and intuition, but I often justify something by doing a calculation out in the paddock. If they don’t match up, I dig deeper into the detail,” Tim says.

“I use lots of gut feel and intuition, but I often justify something by doing a calculation out in the paddock. If they don’t match up, I dig deeper into the detail,” Tim says.

He likes having a budget to create spending discipline and dislikes surprises at balance date.

He’s found his “first crack” at running numbers for a stock trade or a new purchase is usually the best one because of the temptation to manipulate the details to make it work.

His previous experience before starting full-time farming a decade ago has also influenced his approach to asset growth. He remembers as a young finance officer with a stock firm visiting farming families in the mid 1990s who were in financial difficulty.

“It was daunting to deal with them and I told myself then I didn’t want to go through that stress and strain.

Tim could see the impact that it had on them and those lessons have stuck with him.

He always prefers a strong cashflow business and is happy with a cash surplus at the end of each year, rather than being focused on growing their business through more debt.

Gross farm revenue (GFR) in the Upperwood 2021/22 year was a whopping $1748/ha or $182/stock unit. To put this into perspective, it was $500/ha above the class average for semi-finishing, summer-wet farms analysed in the BakerAg financial analysis benchmarking (FAB) results for that year.

When total farm expenses are standardised in the FAB analysis, the Whites spent $830/ha ($86.57/su) including a $66,397 standardised allocation for management wages in the same year. The net result was an exceptional economic farm surplus (EFS) of $918/ha or $96/su, easily the best in the region.

Upperwood’s cash report for the same year shows spending of $627/ha (44% of farm cash revenue) before allowance for $100,000 of rent paid by the farm operating company to the asset-owning family trust.

“In reality, I’m spending about the same as a hill country farm to get where we are. My aim is to keep farm working expenditure between $250,000 and $300,000 each year,” Tim says.

Local farm consultant Ed Harrison says a key ingredient of the Whites’ financial success is they operate a hill country farming cost structure with a finishing farm revenue capacity.

The only standout in the farm working expenditure for 2021/22 (and earlier years) is the low cost for feed and grazing at $31/su, compared with $80/su for the same farm class within the BakerAg FAB.

He says they are not cutting costs in animal health, fertiliser and administration.

“It’s the cropping where they are skimping on costs,” he says.

“There’s nothing else out there that will touch $918/ha EFS. It’s very impressive.”

Tim is a member of the Whangaehu farm discussion group and uses the comparative data from the BakerAg FAB to monitor and compare costs. He also appreciates the class of country he farms allows him the scope to reliably add more value to stock.

As an owner-operator on 420ha effective property, he capitalises on the efficiencies its size allows.

“There are lots of time savings we can grab. Stock shifts are quick and easy, and there’s no need for a big dog team which can be expensive, and there are labour savings too.

Tim says there’s no time lag between changing a plan and getting on with it either. In a big business, owners have to pass information through several hands, but he can cut to the chase and that’s a big attribute of working without scale.

“Aside from administration costs, most costs are all relative to either stock units and/or area. But, you do have to be hands-on, so getting away is not always an easy thing to do.”

When considering a new purchase, Tim prides himself on filtering out the marketing hype and reading reviews to make sure it is a “must have” rather than “could have”. He likes to keep up with new technologies and product developments, but admits he’s made his share of wrong decisions too.

He’s embraced many of the technologies now available, including mobile phone apps which allow him to complete tasks through the day rather than at night.

All dagging and crutching is done with Combi Clamp and Handypieces.

Their scale allows them to do that.

“We’re not dealing with big numbers, so we can get a job done quickly.”

Any machinery or implement that sits idle for two or three years is sold.

His experience in valuation and finance roles before going farming also helped Tim with producing one-page scenario spreadsheets and stock reconciliations, which are critical to get accurate at the start of each year.

He uses Farm Focus, farm financial management and budgeting software. After a settling in phase he’s comfortable with the programme and its capacity to generate future-focused scenario analysis.

Tight control on cropping costs

Upperwood’s easy contour and silt loam soils provide a great platform for crops to be grown to finish stock to higher weights.

A third of the 420ha effective area is flat, another third is easy and the balance is medium hill, meaning close to 250ha could be cropped if required.

The Whites haven’t ploughed a paddock in more than 15 years, preferring the speed and cost savings from direct drilling seed and applying fertiliser by truck.

In the past, paddocks in the programme were sprayed out with glyphosate in early spring, sown in red and white clover, then Italian ryegrass was stitched in by late autumn. Tim says it was not uncommon to get four or five years of good pasture production out of that programme.

But in 2019 and 2020, two hard droughts led to a rethink and a change of system.

He works 12 months ahead to make sure the paddocks chosen for cropping are cleared of Californian thistles, using Versatil at a heavier rate. Paddocks are soil tested and receive capital applications of phosphate, sulphur and lime if required.

In spring, they are sprayed out with Glyphosate 540 at 4–4.5 litres/ha using their own Katipo eight-metre spray rig. With no GPS in the tractor, Tim uses a free downloadable phone GPS app instead and finds that works well.

The phosphate and sulphur plus any lime goes on with ground spreader trucks before it’s sown using a Duncan seed drill with no fertiliser box on it.

Tim says the P and S go on regardless of the test results and he’s prepared to risk not placing fertiliser with the seed at sowing time.

New crop is monitored for slugs and treated if the infestation is sufficient to warrant it.

The seed-mix cost ranges from $100–$140/ha depending on where he can source the seed. He’s happy to use uncertified seed and to trim the sowing rate back from recommended rates.

With $20–$50/ha for slug bait, depending on the level of infestation, another $70/ha for glyphosate and seed at $100–$140/ha, the total cost is $200–$250/ha. Add another $170/ha for fertiliser and the total cost is up to less than $500/ha.

“I don’t compromise on timing, so having our own gear helps with that,” he says.

“Our climate and class of land we have means its forgiving country, but when you cut corners like I do, there is a risk it will backfire.”

He finds sowing chicory at 1kg/ha is sufficient, and red or white clover at 6kg/ha, and plantain at 1kg/ha.

Stitching in perennial ryegrass later means that as the clover and chicory start to go dormant, the ryegrass will come through.

About 40–50ha a year goes into the clover, plantain, chicory and Italian mix, though last spring 55ha went into crop after the tough summers in 2019 and 2020.

Tim’s preferred brassica mix is 3kg/ha of Spitfire rape, 4–5kg/ha of clovers and 1kg/ha of plantain.

It is grazed by ewe lambs through autumn and then ewe hoggets pre-lamb. This last autumn it’s been full of red clover and the resident ryegrass has come back too.

The key to success is selecting paddocks early and ensuring the fertility, drainage and subdivision are right before they enter the cropping programme.

“Fencing and water needs to happen together, hand in hand, and that has given us our biggest return.”

With more than 100 paddocks, ranging from 3–5ha and averaging 4ha, fertility transfer is greatly reduced and there is plenty of flexibility in managing the rotation of livestock.

Many of Upperwood’s electric fences have been replaced with nine-wire quarter-round post fences. Without the pressure of cows and with regular stock movements, they cope well and are a big saving on batten fences plus less maintenance than remaining electric.

After some dams failed in the 2019 and 2020 droughts, the Whites decided to tap into two of their most reliable water sources and reticulate that water using solar-powered and gravity pumps on about 100ha of hill paddocks.

They spent about $10,000 on pumps and another $10,000 on troughs, pipes and tanks, so 90% of water is now reticulated.

Tim says they went for cheaper black plastic troughs because they are half the cost of concrete troughs and easier to install. As long as they have water in them and are well set into the ground, they are fine.

They are trying to move away from using nitrogen but it is a get out of jail card especially when they need to grow feed in early spring to lamb on.

“Our other option is to reduce our trading numbers a bit – and we don’t get hung up on achieving a particular closing number for stock at balance date – before jumping into nitrogen or offloading stock early if necessary.”

At 30c/kg drymatter grown, nitrogen (N) use takes some justification in their system.

“There are not a lot of (livestock) systems throwing out that sort of return at present, so it needs to be well considered before we’d step in with N.”

Page48Environment plan set for upgrade

Staying ahead of the compliance curve has always been important to the Whites.

They have a detailed farm environment plan which is being updated and have been consistently planting riparian, wetland and retired land areas of the farm. Critical water- source areas of the farm are all fenced and planted where appropriate.

Tim and Binds enjoy planting trees and they are great for the aesthetic appeal of the farm.

Planting of gullies and waterways hasn’t been an issue. Poles in the gullies are a natural progression for them.

They have avoided pines, preferring native species and poles for soil stability.

Pole planting has been ramped up in the past 18 months after damage resulting from heavy rains in February 2022.

They’ve tapped into the supply of poles from the Greater Wellington Regional Council and also developed a technique to source their own eco-sourced poles. They planted 500 last year and planned 700 this July.

The extra poles are leaders off the regional council poles, soaked for a week, then placed in holes drilled with an 80mm augur. The key to success is to ram them well and to make sure the fine soil that comes out of the hole goes back down with the poplar stem.

“We take leaders off when they are the size of a wrist and 2.5–3.5m long. They are a little bit ugly initially, but they straighten up nicely in the end.”

Survival rates are 80–90% and to qualify for the Emissions Trading Scheme (ETS), they’ve planted at 60 stems/ha and can still graze those areas too.

Native species are the choice for any retired areas, especially riparian strips, where there are fencing and plant subsidies available.

Running their farm through the Beef + Lamb New Zealand carbon calculator, it is generating gross emissions of 3.5t/ha, almost entirely from livestock.

Methane output was 55,000kg or 130kg/ha (13kg/su) so that the proposed He Waka Eke Noa price of 8–10c/kg, is $4400–$6050 of tax payable.

But with 8ha of poplars already registered in the ETS providing a 10t/ha offset at $55/t (current price), the Whites already have $4400 income to pay the tax.

By the end of 2023, they are targeting another 32ha of poplars, which would generate more than $20,000 at the $55/t carbon price, plus another 15ha of natives offsetting 5t/ha at $55/t for a further $4125.

“If we can get that up to $60–$70,000, that’s up to 10% of our farm income, which will be a big help when the tax on emissions rises in the future.”

Lambing date under review

A flexible and adaptive stock policy is vital in summer-risky Wairarapa.

The Whites are reviewing their lambing dates after a meat processor preference emerged for heavier carcaseweight(CW) lambs at weaning.

They had been steadily bringing their lambing date forward and aiming for a high percentage of prime lambs at 34kg minimum liveweight (LW) for a 14.5kg CW by weaning at 90–100 days. It required lambs to gain 320–375g/day LW from birth, a very challenging goal in the past two springs.

“The last two springs have been dogs to grow a lamb.”

Tim is seriously thinking of pushing the lambing date back to try to better match with their feed curve.

Upperwood’s location and cropping programme brings a good degree of safety for summer- lamb finishing, but there’s more risk moving lambs into the summer without consistent rains.

Their aim is always to feed stock just to their genetic potential, but no more. They are on track to winter about 700kg/ha LW, but it varies through the year. It depends on the trading component in the system. It was above 800kg/ha in March this year.

Before those two tough springs, the Whites had been sending 70% of their terminal-cross lambs prime off their mothers at the minimum 34kg LW. The lift to minimum 36kg LW means they have not achieved that percentage in the past two springs.

Kelso rams have been the maternal sire choice for the past six years in the Upperwood flock of 2000 mixed-age and two-tooth ewes. Rams are now joined from April 5.

Tim’s pleased with the Kelso genetics as a choice to stabilise the ewe flock after some tinkering with different breeds and trialling out-of-season lambing using Poll Dorset genetics.

“We wanted good growth rate, yield and fecundity all in one package and Kelso is delivering that.”

About 60% of the ewes are mated to Kelso maternal rams from April 5 to provide 800–900 ewe lambs which are then culled back to about 600 which enter the ewe flock. The other 40% of ewes go to Kelso terminal rams from March 25 for about 40–50 days.

A portion of the maternal rams are then used for mating the ewe hoggets for additional replacements.

Tim regrets not investing more in his maternal sheep genetics when he started farming and is still frustrated by the “throwbacks” that appear from the old maternal genetics he was using.

“We’re keen to get mature ewe body weights down a bit but that is quite tricky because we want to feed them well to achieve the performance we’re after.”

The Kelso mixed-age ewes typically scan 175% (without scanning for triplets) and Tim estimates there are usually between 10 and 15% carrying three or more lambs.

The ewe hogget in-lamb percentage is building and this year, with 4–5kg more body weight average at mating time, he’s expecting more than 90% to be in lamb.

The Whites’ philosophy is every mouth on the farm has to be a productive one.

“Young stock are the real earners but you need older mouths to create the feed for them.”

Long- and short-term grazing of ewe hoggets has been phased out and more ewes and trading lambs added to compensate.

Tim says grazing ewe hoggets was a lucrative option for their business, taking on ewe lambs in December and returning them as 64kg two-tooths after they had reared a lamb on the farm as a ewe hogget.

But achieving the target body weights in a variable climate and managing a big percentage of young sheep with all the inherent animal health risks led to a rethink.

“Adding value to our own stock stacks up on paper and gives me more flexibility.”

He says as they build the quality of the maternal flock, more ewe hoggets will probably go to the maternal rams and they will keep their ewes lambs as replacements.

The new system still has sufficient flexibility to do a lamb trade if the season and margin allows.

Tim says a return to grazing ewe hoggets is “not fully off the table”.

Ewe hoggets are selected on type and weight before being mated to Kelso terminal rams. The target is a minimum of 42kg however they were forced to drop that minimum last mating to get sufficient numbers to replace the grazing ewe hoggets that were dropped.

Farm consultant Ed Harrison says standouts in the sheep performance for the 2021/22 year were low deaths and missing at under 4%. Also a survival to sale for lambs of 143% in the mixed age ewes and 78% for the ewe hoggets, and a $168/head average for lambs sold.

Compared with the average price achieved by other farms in the same BakerAg FAB semi-finishing, summer-wet class, the Upperwood lamb price was more than $30 higher.

Net income from sheep in the 2021/22 year was $582,471 or nearly $174/sheep stock unit, regarded as the best performer in its FAB class.

The number of lambs born per effective ha for Upperwood was 8.3, almost 2/ha higher than any other farm in the same FAB class.

He says farms with a high number of lambs born per hectare don’t generally win on dollars per head as well, but in this case, the Whites’ result was impressive at nearly $180/head.

He says the Whites were lucky to get big rains in Feb 2022.

“…to their credit, they had lambs on board and they showed the ability to add the cream on top by chucking on an extra $30 to $40 a head on to their lambs that year.”

Thriving heifer trade

Being aggressive and early with cattle buying is a successful formula for the Whites.

They’ve replaced buying in 100kg bulls and killing them at 18–20 months with two heifer finishing systems – a short-term spring option and an annual option.

When the average margin for their first year of annual heifer finishing hit $800, they were pleased the move had paid off financially.

A key to the success of the short-term August to Christmas heifer trade is being in the market earlier than most in the spring and backing the farm’s ability to grow grass to feed them. Buying two weeks later could mean a halving of the $400/head margin they achieved in the 2021/22 year.

Tim likes the “softer” option of heifer finishing over bulls, but admits he expects to take “a bit of punishment” this year because weaner calf prices were higher in the autumn.

Income per cattle stock unit in the 2021/22 year was almost $187.

For the longer-term finishing heifers, his aim is to buy 220kg weaner heifers in autumn, winter them in mobs of 40–50 and grow them at 500g/day. Then feed them to grow at 1.1–1.2kg/day from October to Feb so they are 300kg heavier and killable at 260–270kg CW.

“We’re just taking a break from bulls,” Tim says.

“They are good earners and easy to buy and sell, but they dig holes, wreck things and they are just bastards to manage.”

They are hard to box, there’s always a tail and he is always patching up something around the farm.

“We try to buy outside the grass hype.”

He is not worried about the colour of cattle and happy to buy smaller mobs.

“They just need good bone and type.”

Over summer, the heifer mobs do a bit of grooming work, rotating around a group of paddocks, often returning to paddocks they have grazed before if there is sufficient regrowth. Ultimately, it is hoof and tooth and the ewe flock that manages feed quality.

They haven’t got big paddocks and Tim is not afraid to top paddocks with the mower if he can’t get enough stock there to control it or Californian thistles, the biggest weed on the farm.

“We want to drive a clover-based system here, so the last thing I want to do is spray out the thistles and knock out the clover at the same time.”

Tim is a fan of mowing the thistles first, then spraying with MCPA and Versatil when the clovers are dormant in the cooler months. A rotawiper is used as well, especially in chicory or cropped areas.

He supports online selling platform Cloud Yards and is happy to buy via bidr or through Feilding sale yards. One of the biggest limitations for his location is getting stock trucked back from Feilding to the farm because there isn’t always a truck from Masterton at the sale.

One change in policy is to increase the cattle percentage from 15% to 25% of total stock units. Mopping up sheep worms, prepping country for sheep and saving on labour are the motivations.

He’s also keen to move to once-a-year shearing too, to reduce his shearing costs. The plan is to have all sheep shorn by late February so there’s less wool and hopefully fewer cast ewes when they are set stocked for lambing. He is also hoping he can eyeball body- condition score in the race to ensure those ewes can be separated from the main mob and preferentially fed.

Tim’s aware of the risk of wool yellowing with once-a-year shearing, but at $1.20/kg for the wool now, it is not going to impact the return enough to warrant a second-shear policy.

His Kelso composites don’t grow as much wool as a Romney and this was an influence on his decision to move to 12-month shearing.

Late to full-time farming no barrier

Entering the Wairarapa Farm Business of the Year proved a cathartic and rewarding process for the Whites.

It pushed them outside their comfort zone, but preparing the entry was a rewarding process. They were forced to deeply analyse their farm business and values, then commit it all to paper.

Farm ownership started in the 1990s when they bought the first 130ha of Upperwood, and over the following five years they added another three blocks to create the 427ha farm it is today. Some of the early purchases were at $2000–$3000/ha and they wondered how it would work.

“A lot has changed when you consider values today,” Tim says.

The land and buildings are owned in a family trust that leases it to a farming company that owns the livestock and plant. The Whites say the aim was to create a structure that would make it as easy as possible to leave it to the next generation.

At the same time as they bought their first part of Upperwood, Tim started a role as a valuer for Wairarapa Property Consultants, working alongside Don Todd and Phil Guscott. For the next 12 years, they fitted farming with town jobs and a young family.

But at the age of 40, Tim made the call to come home to the farm full time.

“I really enjoy what we do.”

They have a modest scale which works to their advantage.

Tim says it is hands-on but he enjoys having only one boss to communicate with and that’s Binds.

“We often find our best decisions are made over our morning cup of coffee.”

Binds says her involvement day to day with the farm has been minimal, but she is on call when needed.

“Tim can rattle off all the details of the farm business off the top of his head, but his attention to other details like birthdays is lost five minutes after you tell him something.”

One of the competition judges Geordie McCallum says a huge strength of the Whites’ business is the dynamics of the duo who run it.

“They are a fantastic team. Both have extremely good skills learned from external roles. They work well together because they recognise each other’s strengths and weaknesses,”

He says the Whites have no formal governance structure in place, but good governance starts with a strong husband and wife partnership.

He applauds the Whites’ balance of investments, both on the farm and off it, and their passion for having fun off the farm, including ski-ing holidays offshore.

“When Tim wants to get away for something, Binds will jump in and run this ship and vice versa, but this takes organisation and discipline to do it.”

The standout financial performance of the business is also notable.

“The gross farm income is not the best we have seen, but the efficiency and cost structure is the best we’ve seen,” he says.

“They use their management skills and experience to drive production, and they sustain the farm on the cash it generates.”

KEY POINTS

- 410ha effective at Matahiwi, Wairarapa

- Three main blocks, divided by roads

- Third flat, third easy, third medium hill

- 100-plus paddocks, 3-5ha

- Water reticulated to 80% of farm

- Mostly silt loam soils, suits cropping

- Summer-safe, though rainfall now more variable

- Good infrastructure in place

- Growing 8500kg/ha DM per year

- Produced 274kg/ha of meat and wool in 2021-22.