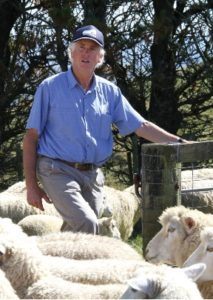

Wairarapa-based farmer and former Nuffield Scholar Derek Daniell looks at the unintended consequences of carbon forestry.

A lot of focus has been on the One Billion Trees programme but the main driver of carbon forestry, farmland planted in pine trees, is the value of carbon credits, cash payouts from year six from planting trees.

There has been a poor take up of the One Billion Trees programme which offers government assistance for planting, but the landowner then relinquishes a chunk of the income from carbon credits.

The programme was designed to encourage the planting of native bush, but 88% of the area claimed for is destined for pine trees.

Why one billion trees?

The Government has set a goal to plant one billion trees in the 10 years between 2018 and 2028. This carbon sink strategy is its response to New Zealand’s commitment (through the Paris Accord) to reduce this country’s greenhouse gas (GHG) emissions.

Having been involved with logging from my farm and other forestry blocks for 17 of the past 25 years, I have strong doubts about the sustainability of the number of woodlots the programme would require. For instance, the logging of hill country say 17 times in the next 500 years will be extremely problematic for a number of reasons, both environmental and economic.

Soil, road and environmental damage

The washing away of soil after logging is a common occurrence and there will be less and less soil left behind. No other civilisation in history has mass-planted this amount of trees. If we do not log them, there is the unsustainability of planting land in trees and just leaving them. Planting trees on hill country tends to be irreversible, so we need to look at the viability of committing future generations to locking up land in forestry for the future, probably under corporate-based farming structures.

Increased forest planting also comes with damage to roads – with one billion trees planted there will be about 50 times the tonnage of logs being carted than sheep and cattle. Other negative side effects include the impacts on invertebrates in water affected by tannins, slash and pollen. The scallop resource in Tasman Bay has already been diminished by these contaminants, and the 10 main scallop beds in the Kaipara Harbour have been reduced to one.

There will also be negative effects on biodiversity from monoculture planting. Pine trees suck moisture from the ground and dry up streams that used to run all summer, killing koura, native fish and invertebrates.

NZ’s native biodiversity is already very low – there are just 58 species of freshwater fish compared to 1279 in Africa, but the water in Africa is always muddied by hippos, elephants and other animals. There are claims that farmers are polluting our streams and rivers with farm animal waste, but our natural ecosystems have already been altered by introducing trout, salmon, Canadian geese and Mallard ducks.

Although the agricultural sector has been blamed for waterway pollution, 80% of cities and towns are non-compliant with sewage and stormwater regulations.

Auckland, Taupo and Queenstown pay little or no fines for polluting beaches and waterways, but farmers do. Also, along with increased logging comes the extensive use of methyl bromide on wharves to control fungi on log stacks. This is a hazard to human health, yet regulators are still allowing this practice until a viable alternative is found.

Landscape, land use and community effects

Another unintended consequence of planting one billion trees will be a dramatic change in the appearance of NZ’s landscape, which will happen if millions of hectares are planted in Pinus radiata. Do we want to have a similar landscape to New Finland and, importantly, what do tourists want to see?

A further issue is world deforestation – it is estimated about 500,000 hectares of natural forest is being cut down every year around the world and the land converted to some form of farming. My question is why decimate our pastoral industry, which has been the backbone of the NZ economy for 170 years, at the risk of achieving nothing on a global scale?

Not only will the rural landscape be altered, but this will happen in conjunction with urban creep. The urban area in NZ now covers one-third of the area of dairying and lifestyle blocks cover 850,000ha. We have unwisely used some of our best food-producing land for housing.

As a farmer I also have serious concerns about the effect of blanket tree planting on small rural communities and provincial towns. For instance, as more and more farms are planted, communities could gradually die. Non-forestry-related employment could wither, local school rolls go down and the few left in the area might be constrained by reduced services, vehicle safety issues from logging trucks and enhanced fire risk.

Economic viability

From an economic perspective, there is uncertainty over future timber markets. While there is an assumption that there will be a profitable market for logs in 30 to 40 years’ time, NZ is very exposed to one market – China – for exports. However, as China becomes more self-sufficient in their wood supplies this market could progressively diminish – just as NZ is expecting another ‘wall of wood’ from the One Billion Trees programme. Also, unlike the cropping and meat industries, over the past 25 years there have been longer periods of lower than higher log prices.

Hidden costs of the carbon sink strategy

There will also be hidden costs in the carbon sink strategy to be carried out through the One Billion Trees programme. For example:

- The lost export income from shrinking the sheep and beef sector

- The payment of carbon credits to those landowners who plant trees, including overseas investors

- The loss of rural communities, as well as the capital tied up in houses, schools and other infrastructure, e.g. the Affco meat processing plant in Wairoa

- The much-increased wear and tear on roading caused by logging

- The increase in unemployment benefits as rural communities become hollowed out – one estimate has the current plan costing the average household $7000 per year by 2050.

Taxing ruminant emissions

Related to the discussion about reducing GHG emissions, the Government could be the first in the world to tax ruminants for their natural emissions, despite ruminants evolving 90 million years ago. However, the other 1.2 billion cattle, one billion sheep and 450 million goats in the world will not be taxed. Furthermore, 80% of these are in developing countries where billions of people depend on them for survival and it is difficult to ask them to change their eating habits quickly.

In my view, NZ should only tax animal emissions if all other countries are going to do the same. Will countries growing rice tax their farmers for the methane emissions from paddy fields, which are greater than all the livestock emissions in the world?

Pastoral farming is one of the most natural forms of farming plants and animals together. NZ exports enough nutrient-dense, protein-rich food to provide for 40 million people, eight times our population. Does any other country export such a surplus to help feed the world? NZ has 0.2% of the land in the world, but produces 0.6% of the world’s food. GHG emissions should therefore be calculated over 40 million people, not five million. Also, if we produce less, some less-efficient food-producing countries will have to produce more. Cows, sheep and deer are the perfect filter to transfer pasture, indigestible to humans, to a suite of nutritious foods.

The pastoral industry has shrunk from grazing 60% of NZ to 40% now. Ruminant numbers have also shrunk from their peaks, sheep from 70 to 27 million, beef cattle from 6.4m to 3.6m, and deer from 1.8m to 850,000. Even dairy cows have declined from their peak number of 6.5m.

Global ruminant numbers have been static for the past seven years so their short-term GHG cycle has stabilised. But global oil output, at 94m barrels of oil per day, is pumping fresh CO2 into the atmosphere every day. For many years New Zealand pastoral farming has been demonstrating a 1% annual improvement in GHG emissions per kilogram of product, but this continual improvement in productivity is not matched by the overall economy.

Putting NZ agriculture at risk

The global population keeps rising as long as there is enough food, but the projection for the current 7.7b to reach 11.2b by 2100 is of great concern. The increasing stress on natural resources will be extreme, in particular as cities encroach on food-producing land and wilderness continues to be taken over by people in Africa, Asia and South America. Every extra person will add to GHG emissions.

NZ is naive to think that other countries are going to undermine their key industries to meet promises made in the Paris Accord. A recent article in The Economist outlined the lack of progress made by all the European nations in meeting their interim targets. The US has not signed the Paris Accord, and China and India (the biggest GHG emitters in the world) plan to have large increases in GHG emissions by 2030.

In my view, there is no point in NZ putting at risk its most productive and long-term sector – agriculture. Similarly, the symbolic gesture of closing down exploration for oil and gas is equally naive when world demand is still increasing. The oil industry provides the raw resources for three other large industries – synthetic fibres, plastics and nitrogen fertiliser. Without nitrogen fertiliser, the world’s farmers would grow enough food for only three billion people and 60% of the global population would starve.

Possible solutions – wilding pines and taxing air travel

As a solution, if the Government considers more trees in NZ will help the global situation then let wilding pines spread across our barren landscapes. At a spread of 90,000ha per year, this would provide a temporary offset for the 45% increase in NZ’s population since 1990 and the 93% increase in the use of fossil fuels. Importantly, it would cost nothing and would save the money being spent on trying to prevent the trees spreading.

Alongside wilding pines as a solution, I will suggest that there is a departure tax for every flight in NZ, which will be graduated on hours in the air – I would suggest $50-$100 per hour – so a 16-hour flight to Houston would cost an extra $800-$1600. This excellent extra source of tax revenue would help spread the load away from our efficient farming industry, one of very few sectors in the NZ economy that has continually improving productivity.

- Derek Daniell runs Wairere, a ram breeding enterprise based in the Wairarapa. Wairere also has a ram breeding farm in Victoria, Australia, and joint ventures selling rams in Europe and South America. Email: derek@wairererams.co.nz

First published in the NZIPM magazine The Journal.