Industry leaders need to listen

Sharing the pain of reducing emissions will create winners and losers and to attempt to present a united front on this topic is much harder, James Hoban writes.

Sharing the pain of reducing emissions will create winners and losers and to attempt to present a united front on this topic is much harder, James Hoban writes.

More than a few farming friends have surprised me recently. People who have led the charge on advocating for fair water, nutrient and biodiversity regulations have buried their heads in the sand over He Waka Eke Noa (He Waka).

This has been for a range of reasons including frustrating experiences putting time into previously futile submissions, pandemic noise and onfarm distractions.

The main reason for apathy appears to be consultation fatigue. Those who have ignored He Waka until now need to switch on quickly and do some reading.

While it might be tempting, studying the five-page executive summary is not enough. Those who have taken the time to become enlightened, might well be feeling alarmed at the direction our industries are heading. From a sheep and beef perspective perhaps the most troubling aspect of the direction of travel is that our sector leaders are marching together holding hands.

Industry leaders might point to belated victories that were achieved on winter grazing rules. It is true improvements were made to draconian, impractical regulations after extensive farmer and industry pushback but greenhouse gas emissions is a different beast.

Sectors largely wanted the same thing with winter grazing rules. A win for the dairy sector in that case was also a win for the person grazing a dairy farmer’s cows. Sharing the pain of reducing emissions will create winners and losers and to attempt to present a united front on this topic is much harder. Taxing emissions stirs up the same demons and difficulties as nutrient allocation and looming biodiversity regulations.

We are reminded by our industry leaders that the ETS is a worse option than He Waka options one and two – but now some informed farmers are wondering if the ETS would be better – at least as a stop-gap. That shows a major disconnect between industry leaders and their farmers.

He Waka schemes are not accounting for our sector histories. The sheep and beef sector has been shrinking while dairy development has boomed. In Country-Wide February, consultant Deane Carson noted that “Industry contraction can represent a climate cooling. Sheep numbers have declined by 53% since the 1990s and lamb production has decreased by 9%. When He Waka proposes a tax rather than a credit, questions will be asked.”

Why are we waiting for farmers to ask these questions? Our leaders and policy people have been involved with He Waka for a long time now – why have they not pushed this reality hard enough to have it adequately recognised?

Somehow the sheep and beef leaders have decided that using a recent line in the sand as a starting point, therefore ignoring historical sheep and beef emissions reductions and dairy growth, is fine. Dairy farms deserve reward for their production efficiency but it is misleading to ignore the growth and development as a sector and the increase in their emissions over time. Starting from a near fully developed point in time heavily favours the dairy sector.

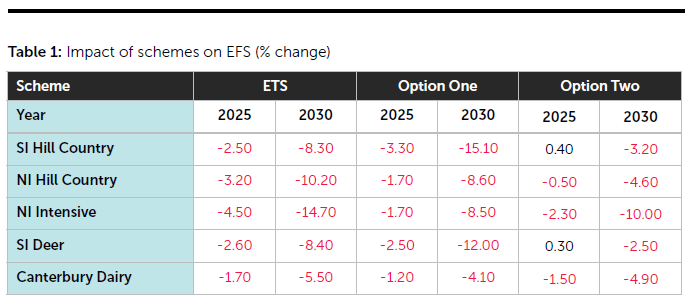

Table 1 shows He Waka’s forecast figures that the ETS, and options one and two would have on economic farm surplus in 2025 and 2030.

The South Island hill country farm modelled is selling 73% of lambs store and all calves except replacements. Because option two is at a processor level these store animals are not directly levied so the impact on EFS is likely to be much greater for SI hill country farms who look to finish more of their own stock.

Will the same lamb traders who drop prices on weaning day or want wet weather liveweight adjustments fail to pass on a new cost to a store lamb seller? To believe so would be greatly underestimating them. The SI deer farm is a version of the SI hill country farm where the sheep and beef aspect is scaled back to 53% of the business and deer makes up 47%. It is also heavily breeding focused.

The dairy farm is running about 800 cows. The SI hill farm is running nearly 3600 ewes, 1000 hoggets and 280 cows plus replacements. The NI hill country farm is running about 1700 ewes, 400 ewe hoggets and 157 cows as well as finishing all their own cattle and lambs. The NI intensive scenario includes some beef cattle trading and dairy heifers.

When it comes to reducing emissions dairy is still offering the usual solution; ‘we will technology our way out of this.’ Given adequate time and incentives that might be true. In the meantime, to satiate the public appetite for change there is one prominent way emissions will reduce and that is through land use change. Hill country farmers removing animals from the planet will reduce emissions and this is one of the few meaningful levers an extensive farm has to pull.

That means either option one or option two will equal more sheep and beef land being planted in trees. This will impact rural populations and services. If we are okay with that as a country then we can make that decision with our eyes wide open. It is not pie in the sky and it is not precious or negative speculation – it is logically inevitable that hill country + option one or option two = less livestock + more trees. Under either He Waka option we will ‘share the pain’ with intensive farmers to the point that some extensive farmers make the call to change their land use to trees – whether under their stewardship or that of a prospective buyer.

If the material we have received in our mail is anything to go by then roadshow meetings will be slick sales pitches. The opportunity for sector comparison and critical scrutiny at these meetings will be limited. Will disadvantaged hill country farmers be prepared to highlight inequities in front of DairyNZ reps and local dairy farmers who may well be friends, BOT colleagues or side-line company at local weekend sport?

True consultation should not be about persuasion or defending proposals. It should involve industry leaders listening more than they speak and it should result in some changes. Anything less than this is tokenism.

At best, industry leaders are massively overestimating the level of He Waka understanding among farmers. At worst, they know we have not fully understood what we are in for yet so it is a good time to tick a consultation box.

Behind the scenes leading farmers are telling farming leaders the options are not good enough but their pleas are being met with a defence of He Waka and a reluctance to listen. Do those leaders really know better than their levy payers? Or is the desire for political solutions side-lining strong advocacy for hill country futures?