Beware unseen sub-clinical FE

Rural professionals often say unexplained production losses in beef cattle can sometimes be caused by unseen subclinical facial eczema.

By Dr Ken Geenty.

The debilitating disease, facial eczema (FE), is caused by liver damage from the fungal toxin sporidesmin ingested with grass-based pasture.

Veterinarians can test for FE-induced liver damage from blood levels of the enzyme GGT (gamma-glutamyl transferase). Also, meat processing plants can sometimes provide information on bovine liver damage, though regional data from them are patchy.

The Government’s Animal Health Laboratories (AHL) have detailed post-mortem data on tissue samples from animals suspected by farmers or vets of having FE. However, this information can be skewed as it only contains results from animals tentatively thought to have FE.

Farmers should be vigilant in most years between January and May to detect danger periods from rising spore counts on their farms. Most veterinary practices have spore counting services and can advise of looming risk periods and treatments. Comprehensive weekly regional consolidated reports on spore counts, indicating a natural FE challenge to animals, can be obtained from the Gribbles Veterinary link – https://www. gribblesvets.co.nz/facial-eczema-

These reports will show when regional spore counts start trending above the FE risk level of 30,000 spores/gm of pasture. This should be a trigger for farmers to begin preventive and remedial treatments.

In 2020 I examined data from meat companies and AHL, supported by Beef + Lamb New Zealand, and found it to be inconclusive. However, it did show prevalence of sub-clinical FE wasn’t as great in beef cattle as in dairy. Incidence varied markedly between years, and the disease was most common in North Island areas and to a lesser extent in the central to upper South Island.

FE is not considered as serious in beef cattle as in dairy cattle and sheep with no solid quantification on prevalence. It’s well known that in some areas with humid weather the disease can seriously affect ruminants grazing grass-based pastures when ground temperatures are above 12C and humidity is high.

Animals affected include cattle, sheep, deer and alpacas. Horses are not susceptible.

The threat is greatest when rain follows a dry spell and there is dead litter at the base of the pasture. Conditions ideal for mushrooms also favour the fungus Pithomyces chartarum which produces sporidesmin, the toxin causing FE.

A couple of years ago the farmer-based facial eczema working group discussed FE in beef cattle with facilitation from Ruakura geneticist Neil Cullen and Hamilton-based AgFirst consultant Bob Thomson. Main points were that beef cattle are more tolerant than other ruminants and tend not to visually show clinical signs. There is greater prevalence in dairy and dairy cross animals.

Although liver damage data from meat processing plants was inconclusive, it was thought sub-clinical FE is probably much more widespread than farmers realise. A DairyNZ supported survey a few years ago showed widespread sub-clinical FE not visually evident in dairy cows.

More recently, central North Island consultant and Wormwise manager Ginny Dodunski has said for every blood or post-mortem liver sample submitted to animal health laboratories there may be several visually diagnosed cases not sampled but instead used as a trigger for treatment. And former vet Jeremy Leigh, now farming in north Waikato, said that Friesian cross beef animals appear most susceptible to FE. He considers traditional beef breeds such as Angus probably have greater natural resistance to the disease. Jeremy noted that FE resistance had been successfully bred into sheep in the area so for them the disease was not a problem.

The cost of FE to livestock industries is huge. Past estimates by the FE working group show an industry average of more than $500m annually with beef cattle predicted to contribute up to $80m if incidence approaches that in sheep. However, this extent is unlikely as beef cattle, particularly on hill country, often graze pastures not presenting an FE challenge.

If spore counts rise above risk levels, beef producers should contact their veterinarian for procedures to test for sub-clinical FE. This will probably involve collection of blood samples from some animals.

Producer industry groups B+LNZ, DairyNZ and Deer Industry NZ are actively working to combat the potentially worsening FE problem and have helpful information on their websites.

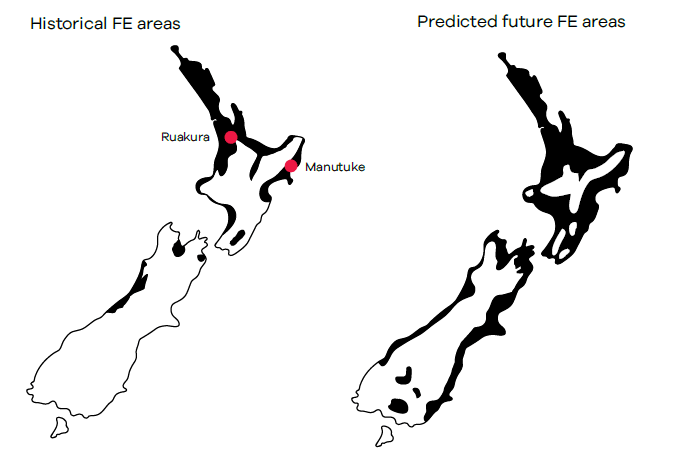

Farming areas most affected by FE are generally north of Taupo and the east coast north from Hawkes Bay. But there is wide variation between years, depending on climate. A severe outbreak in 2016 included the Kapiti coast and large parts of the South Island.

Ruakura scientist Dr Margaret Di Menna predicted some time ago that average season historical FE risk areas, estimated at about 20% of available grazing land, would increase to a predicted 70% with three degrees global climate warming (Di Menna et al. 2009, NZ Journal of Agricultural Research). FE experts say the bad FE year of 2016 surpassed this prediction with much wider areas affected.

The toxic fungal spores containing sporidesmin eaten by grazing animals cause damage to their liver and bile ducts. Because they can’t release bile and waste products they become highly photosensitive with chlorophyll overload, often causing skin around the face and points to break out with weeping dermatitis and scabby rashes around the face and legs.

Distressing symptoms with clinical FE include frequent urination, restlessness, rubbing heads against posts and gates and seeking shade to avoid sunlight.

The vast majority have unseen sub-clinical FE

Importantly, animals showing these external clinical symptoms are only the tip of the iceberg. For every affected animal seen there will be five or 10 others with unseen sub-clinical FE. In a herd of beef cattle with up to 20% clinical cases it’s very likely 100 percent of the animals have sub-clinical FE causing lower production and profit. Animal deaths often occur with clinical FE.

There are several options for farmers for prevention and treatment of FE including –

- Early treatment of animals with zinc, which lessens the toxin’s impact.

- Spraying pastures with fungicide to kill the fungus.

- Removing animals from grass-based pastures to safer pastures or crops.

- Breeding for FE tolerance using proven sires.

- Ken Geenty is a primary industries consultant