James Hoban

Autumn calf sales have offered sellers rewarding prices across four good years. The calf price had been reasonably solid for three selling rounds with an apparent new bottom. This buoyancy has come to a crashing halt in 2020.

Calf prices started low and have continued to drop with Covid-19 and widespread drought seemingly to blame.

At the time of writing we have our own selling decision to make. We have spent three years increasing cow numbers and selling only small lines of calves. Our plan was to sell 100 calves in 2020 – up from 60 in 2019 and 25 in 2018. We have previously sold some spring store cattle after wintering them on fodder beet and sold weaned calves in autumn as well as finishing cattle.

With steer calves trading at $2.80-$3.00kg liveweight and heifers at $2.50-2.70kg LW what is best – selling now or selling in spring?

If we hold calves we have to accept the risks of a further price drop off a difficult winter. There are always stories of people buying calves in autumn, filling them with feed through winter and selling them in spring for a disappointing margin.

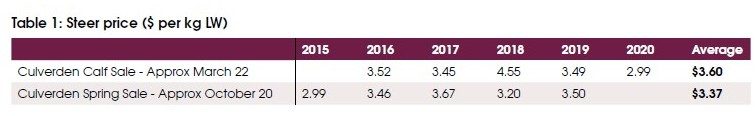

Table one compares March sale prices with spring sales. Line one shows the steer calf price for traditional beef breed lines at the first Culverden calf sale, always around March 22 while line two shows the same calculations from the Culverden Spring cattle sale around October 20.

While the sale prices vary across regions Culverden offers a reasonable yardstick for our calf selling options. It was also the only local sale completed before Covid-19 interrupted proceedings this year.

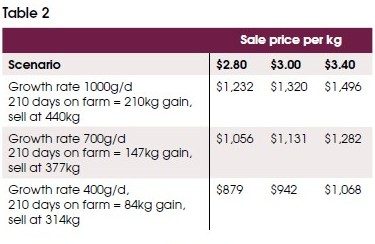

If we look to sell 230kg steer calves now they will be worth $690 at $3.00/kg. Table two shows what they could be worth in spring at various weights and a range of prices.

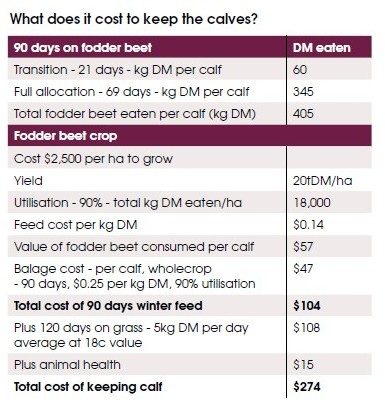

If we keep calves they will spend winter on fodder beet and balage. Assuming we sell them at the October sale and they spend 100 days on fodder beet, what does it cost to winter them?

For this exercise a yield of 20 tonnes is used as well as actual costs for growing and making whole-crop balage and growing the fodder beet. These are variables which could be different on other farms. The total cost of feeding a calf in this situation is $274. This figure does not allow for deaths, commission and debt servicing.

For any scenario from table two to be worthwhile, it must cover the autumn sale price of $690 plus the feeding costs of $274 plus any other costs which arise. Sale price must be $964 in October to break even on that calf. Table two shows that there is a profit margin provided animals achieve reasonable growth rates and the price does not crash into new territory. At the five-year average spring price of $3.37/kg LW and 700g growth rate a calf will sell for $1270. This is a profit of $306.