By: Ken Geenty

Ewe’s milk not only makes lambs grow like crazy, but is also ideal for a range of high-end dairy products like cheese, yoghurt, ice cream, infant formula, and human nutritional supplements.

The milk has high nutritional value. With more than twice the fat and protein of cow’s milk, and stacked full of healthy minerals and vitamins, it’s no wonder lambs commonly double their birth weights in the first three weeks of life. Ewe’s milk has total solids of 18% compared with 12% for cow’s milk, and contains healthy mid-chain fatty acids for humans. The milk lacks the carotene pigment in cows’ milk, and the smaller fat globules give a homogenised likeness, meaning products are invitingly smooth and light coloured, giving unique consumer attributes.

Once, when I was expounding the virtues of ewe’s milk to well-known Southland farmer and friend Robin Campbell, he kindly retorted, “I know Ken, that’s why I feed it to my lambs!”

“Once, when I was expounding the virtues of ewe’s milk to well-known Southland farmer and friend Robin Campbell, he kindly retorted, ‘I know Ken, that’s why I feed it to my lambs!’”

Internationally there has been much research into sheep milking both for lamb production and development and marketing of dairy products. Outlined here is some of my early research with the Ministry of Agriculture and Fisheries at Templeton Research Station near Christchurch and at Lincoln University in the 1970s.

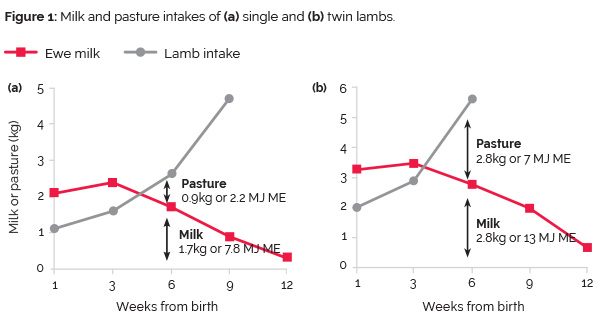

The focus of the research as part of my masterate, supervised by the innovative late Dr Karl Jagusch, was milk production for optimum lamb growth. Lamb milk consumption was measured from lamb water turnover using a radioisotope called tritium as tritiated water, and ewe milk production estimated by hand milking after injecting the letdown hormone oxytocin. It was discovered high milk-producing ewes, particularly those rearing twins, had much more milk than lambs could cope with during early lactation. Generalised feed intake trends for single and twin-lambs suckled are in Figure 1. Twin lambs consumed more pasture than singles by week six of lactation because of less milk being available to each lamb.

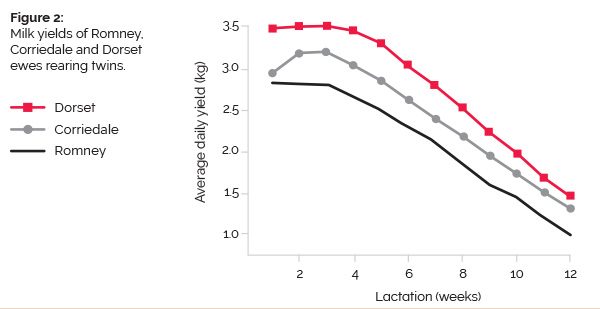

Of the breeds studied, and rearing twins for maximum milk production, Dorsets produced more milk than Romneys and Corriedales as shown in Figure 2. There were large variations in milk yield within each of the breeds.

Of the breeds studied, and rearing twins for maximum milk production, Dorsets produced more milk than Romneys and Corriedales as shown in Figure 2. There were large variations in milk yield within each of the breeds.

By the mid-1970s, when machine milking of ewes had developed at Templeton, it was decided as a brave progression to investigate sheep dairy production with Dorsets for the first time in New Zealand. Back in those days seemingly outrageously different projects sometimes slipped through the system. I was delighted when my boss, the late Dave Joblin, said, ‘yep, let’s give it a go Ken’.

The research was part of my PhD on efficiency of energy use in lactating ewes, under the expert research tutelage of Professor Andrew Sykes. Some 90 Dorset ewes were machine milked over two years after the removal of lambs at birth and serially slaughtered to measure changes in body composition to determine energy transactions. Findings were that ewes utilised dietary energy at 64% much better than mobilising body fat reserves at a lower efficiency of 42%. Losing ewe body weight to maintain milk production is therefore very inefficient, particularly because regaining lost body weight has high feed costs.

Sheep dairy production over a five- to six-month period with Dorsets unselected for milk yield was about 140 litres. A survey of the world literature at the time surprisingly revealed this dairy yield was similar to that of the famous Lacaune breed historically used for dairy production in France. Spectacularly, yields for the Lacaune have since increased to more than 500 litres per ewe lactation following intensive genetic selection over 30 years.

In the Templeton programme applied research showed udder squeezing as milk flow declined increased yield by 20%, once-daily milking only reduced yield by 15%, and dairy yields were highest with lambs removed soon after birth. Measurement of udder size showed little impact on yield, but udder shape was more important. Teats pointing straight down with a cleavage between gave the best results.

Lactation curves for dairy milk were flatter than those for suckled ewes subjected to regular lamb suckling stimuli. Over the initial 12 weeks of lactation dairy ewes produced about 74% of milk from suckled ewes. However, without the lamb suckling influence milk volumes with dairy ewes declined less rapidly and persisted longer.

With about 90 ewes being machine milked, a small tanker took milk surplus to research requirements daily to the Banks Peninsular Barry’s Bay cheese factory for negotiated trial manufacture of feta cheese. About five local farmers were enlisted to boost milk quantities.

An open day on sheep dairying at Templeton in August 1979 attracted 260 farmers with much interest and positive feedback. However, due to lack of a strong marketing plan, and in the absence of capital injection to develop scale, sheep dairy production fizzled out in Canterbury after three years.

Later waves followed, starting with an Agresearch sheep milking project at Flock House the following decade providing milk to Kapiti Cheeses, with products developed and marketed successfully.

Industry took off

The fledgling industry really took off in the first two decades of this century. Spearheaded by progressive corporates, prepared to invest and with significant infrastructure and smart product development and marketing, the industry has thrived and continues to expand.

The biggest players have been Landcorp’s Spring Sheep, Maui Milk near Taupo, and Southland’s Green River. Modern milking platforms have been developed including a French designed rotary system at Maui Milk. Throughputs of more than 200 ewes an hour are common with these modern setups.

With a world-leading sheep industry NZ has a great platform for the ongoing development of sheep dairying. Some very successful genetics have been developed from specialist milking breeds in combinations with local breeds. Composite dairy breeds or crosses based on imported Lacaune, East Friesian and Awassi are used. Some are crossed with NZ Coopworths as a lower cost option. Daily milk yields with the specialist dairy breeds are 2 to 4 litres per ewe, whereas those crossed with Coopworths or other local breeds yield 1.5 to 2 litres per ewe.

Potential income from ewe’s milk is very attractive. Gross income per dairy ewe at a price of $12 per kg of milk solids or $2 per litre can reach $1000 at high end yields or about $700 for lower levels about two litres per day.

Sheep dairying has many similarities to dairy cow production. Liberal feeding on top-quality pastures during the milking period is king, with rotational grazing a good option. Expensive animal houses seen overseas are not necessary for sheep dairying as our intensive outdoor sheep systems have efficiently evolved and are well proven with world-leading production levels.

• Dr Geenty is a primary industries consultant