The little things add up

A Manawatu couple have built an award-winning farm business based on proven science and paying attention to detail, Terry Brosnahan writes.

A Manawatu couple have built an award-winning farm business based on proven science and paying attention to detail, Terry Brosnahan writes.

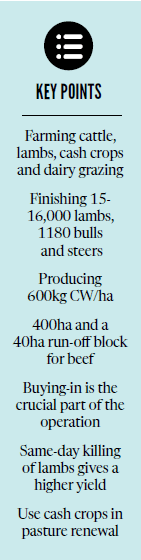

Ian and Steph Strahan are all-grass finishing 15,000-16,000 lambs, and fattening 1180 bulls and steers on 400 hectares at Kiwitea, near Feilding.

Their aim is to grow as much grass as possible and utilise it best by producing as much high value as possible.

Since the Strahans’ farming operation was profiled in Country-Wide January 2020, they have made slight changes to the operation. They are now finishing up to another 2000 lambs and 80 more cattle a year. They produce 600kg CW of meat/ha, aiming for a gross farm income of $4000/ha and average 23-30c/kg drymatter over the whole farm.

The economic farm surplus is $2000/ha and the farm working expenses 50% of gross farm income.

Their performance was impressive enough to win this year’s Wairere Central Districts Red Meat Business of the Year.

Head judge Sean Stafford from ANZ said the farming operation had great balance between sustainable farming practices and making money.

He says Ian’s attention to detail is impressive which underlies their success.

Steph, who has a background in marketing, finished running the local farmers’ market earlier this year and had time to have input into the farm before her next project.

The couple won $10,000 in cash and $10,000 worth of farm products.

The Strahans’ buying in price is still the key to the operation with stock sourced through agents, some private deals and the Feilding saleyards. Price per kilo is king.

The farm is run like a grass factory with attention to detail adding up to bigger returns.

For example, same-day killing with meat company Ovation at its Feilding plant gives a dressing out yield of 43-46% (hot carcase). They have supplied Ovation for 12 years.

Lambs weighing 20-22kg carcaseweight are loaded on the truck and killed in six hours. Ian has compared this with lambs sent to be killed further away and the drop in meat yield can be from 250g up to 750g in one case. At $9/kg, that’s $2.25 to $6.75/lamb.

Yield will vary due to wool length, age and the time of the day with more gutful in the afternoon affecting liveweight.

Ian says careful management of lambs pre-slaughter is worthwhile so they take care when loading stock including no dogs in the yards. The 50c/kg downgrade to cutter for bruising or poor injection abscesses adds up.

Having clean lambs sometimes means not having to shear, but mainly it retains the presentation premium, worth another 15c/kg. They avoid handling lambs on wet days, put gravel on the tracks and have covered yards.

The cattle are killed November to March, lambs October to March. About 85/cattle/week are killed, and at the peak in winter, 1000 lambs/week.

While Ian doesn’t zero-base budget, i.e: each year go through each item of cost and justify each item, he does look closely at costs and question them.

“I try to keep an open mind and look at it like a blank canvas.”

Ian’s decisions are based on sound science and proven products, especially with fertilisers.

“All the studies have been done and there’s no free lunch.”

Keeping tabs on costs

Ian uses a spreadsheet to keep a grip on the escalating input costs, especially fertiliser. For every kilo of nitrogen he expects a 15-20kg DM/ha response, depending on the time of the year.

From there he can work out the product value of the grass and whether or not it is worth it.

“I put on urea at $1400/tonne this autumn and it was still worth doing.”

A major change was to soil test every paddock in 2020. From looking at the pastures he was suspicious of the soil fertility.

The savings in fertiliser have been at least double the $6000-$7000 spent on soil testing.

They grow 70ha of cash crops, peas and winter wheat, through which they renew their pastures every five years.

Ian believes real farm inflation will hit in the spring and show next financial year because a lot of the input costs like chemicals, fencing gear and fertiliser were bought earlier and are on the paddock.

“There are no ifs and buts, prices are real and rising across all sorts of items.”

A full-time shepherd and casual work on the farm.

The Strahans’ business is strong in all three parts of sustainability; economic, environment and social.

Ian is chairman of Haynes creek catchment group and deputy-chair of the Manawatu River Catchments Collective. It is an umbrella group which handles distribution of funding and supports its 10 catchment groups.

He told the competition judges his three key principles for their farming operation are:

- “If you can’t measure it you can’t manage it.”

He says a depth of knowledge is needed to make proper decisions. Which forages best suit the farm, their production at different times of the year and animal growth rates all need to be known by farmers monitoring their own farms.

- “The days of wandering along to a sale and trying to work out a margin from something you are buying is not going to cut it nowadays.”

Every farm is unique. Farms may have the same climate and soils, but the management practices and skill sets etc are different.

“There is no other one like it.”

Instead of doing what others have done a farmer needs to look at all their own physical resources and make a plan accordingly.

- Take advice: Farmers are often terrible at taking advice. They are multi-skilled but can’t be experts at everything, especially with all the new technology.

He says there is a mass of advice out there and most of it is free.