The breed or buy-in ewes question

More profitable alternative enterprises may be accommodated if replacement stock are bought or grazed off farm, Tom Ward writes.

More profitable alternative enterprises may be accommodated if replacement stock are bought or grazed off farm, Tom Ward writes.

The question of whether or not to buy or breed replacement female livestock gets more complex the more one looks into it. I found myself considering the option of grazing off in tandem with buying replacements.

Replacement livestock often do not reach their potential, despite having plenty of time to do so, or other livestock classes may be pinched when the replacements are being favoured by the farmer.

Where seasons can be very dry, or just very variable, buying replacements (or grazing off) can reduce risk. Furthermore, more profitable enterprises may be accommodated if replacements are bought or grazed off farm. Dan Jex-Blake from Wairoa-Gisborne has planted apples on the flats of his hill country farm.

Not rearing replacements on farm can guarantee a well-grown replacement, and buying replacements can improve a farm’s genetics and simplify a breeding programme. A downturn in any sector can be taken advantage of to accumulate superior livestock at a good price. However, the availability of good quality replacement female livestock can be a risk where an industry is in relative decline. Buying in animals can expose the farm to foot problems, and possibly intestinal parasites, although the latter should be managed.

Feeding young, growing livestock creates no immediate income. In fact, breeding stock of all types are only really profitable between parturition and weaning. The analysis later in this article will illustrate that.

Buying females can facilitate the use of hybrid vigour, for example where composite rams are used over Romney ewes, to produce a larger, more fecund, better milking ewe with lambs larger at birth. Breeding the Romney ewes would complicate management and reduce the number of sheep available for hybrid vigour.

It is not just other enterprises that can utilise additional feed. Some parts of a breeding animal’s annual cycle are very responsive to feeding. A ewe maintaining a body condition score (BCS) of three or more in winter will improve at lambing, ewe survival, ewe milking, lamb survival, lamb birth weight and lamb growth rate, It will bring forward lamb slaughter date and lamb sale size. The net benefit can exceed $1/kg DM eaten.

An example of better feeding with breeding hinds is to reduce summer feed demand by selling wether lambs, and/or all female lambs store in December. If that extra available feed went to the breeding hinds, the hinds would mate earlier and show other benefits similar to the ewes in the paragraph above.

Just lowering the stocking rate reduces feed pressure and makes livestock performances more reliable. Buying replacements could be used as a temporary measure coming out of a drought. Especially with a two-year flock (buy five year olds), there is the opportunity to heavily de-stock over summer and buy in-lamb ewes in July. Very valuable in a summer-dry area, especially on a small farm.

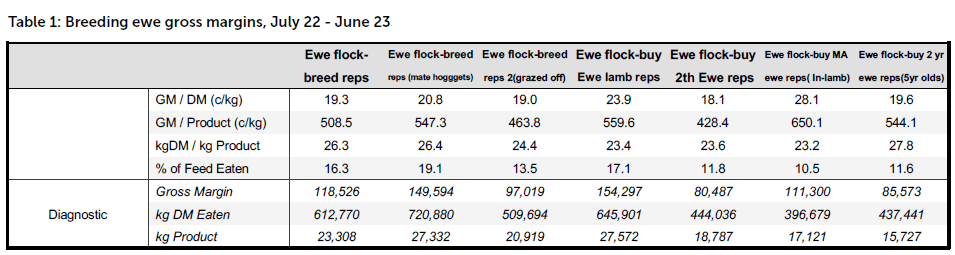

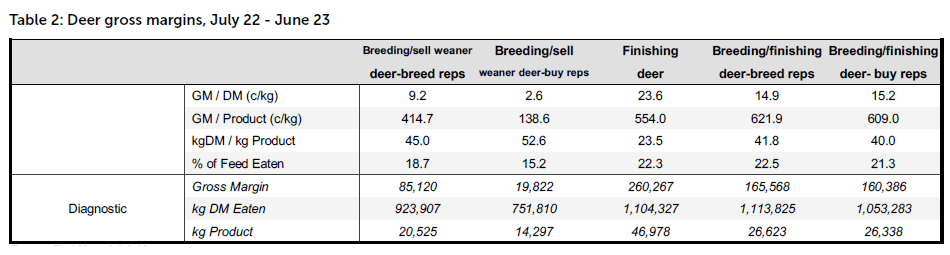

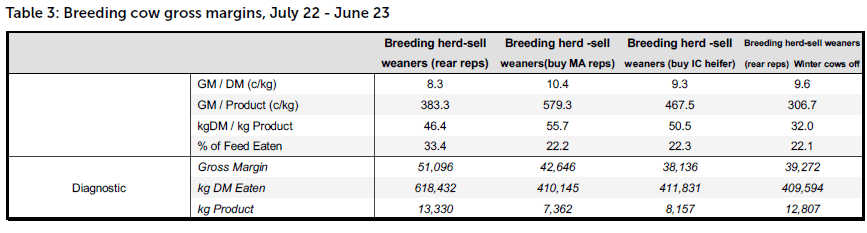

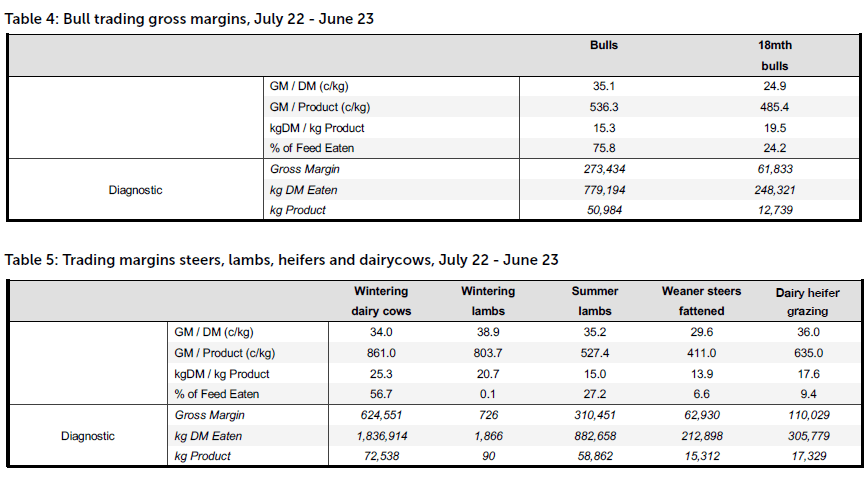

The Farmax gross margins tables attempt to give a snapshot of various buying replacements’ options compared to breeding replacements in breeding ewes, breeding cows and breeding hinds. The final two groups of gross margins show alternative enterprises that could be inserted into a farm in place of a replacement breeding policy. What needs to be stressed is the danger in relying on gross margins to assess the profitability of an enterprise. A full-farm budget needs to be prepared to compare the new total operation with the existing full programme.

Wintering breeding cows off farm allows drought relief, and possibly the shutting up of paddocks for calving feed (better calving, better mating, bigger calves). Winter beef cow grazing can be cheap if feed is rough or plentiful, which can occur if in a different province. Grazing can be free, if for a short time, or between 10 and 20 cents/kg DM, at 8kg DM/day consumption, that is $6 to $12/head a week. If you wanted better quality feed, such as Italian ryegrass or fodder beet, 30kg DM is still only $18/head/week.

Pasture feed can increase in value when pushed forward to spring, and cows, if in very good order, can be wintered on 7kg DM /head/day.

Breeding ewe gross margins

These are all based on 700 ewes. The various sheep gross margins show little variation, all except one falling within a 18–23 cents/kg DM range. That exception, buying in-lamb mixed-age ewes, has a 25% better gross margin/kg DM eaten efficiency. This result is primarily due to the bought ewes arriving on farm only just before lambing, and the sale ewes leaving very soon after weaning. It is essentially a two-year flock, with the time the ewes are dry, minimised. While it shows a relatively low total gross margin (from 700 ewes), about 263,000kg DM less of onfarm dry matter is needed.

Depending on the quality and timing of this drymatter, there is the opportunity to put this feed into a higher yielding enterprise. Or if the farm is located in a summer-dry region, this feed saving could be used to improve farm systems’ flexibility. The most profitable option in this group of gross margins which is efficient and not using too much extra feed is buying ewe lambs for replacements.

The variations of mating hoggets, and grazing hoggets off are included as these are popular options. The former increases profit and maintains efficiency with the latter saving a reasonable amount of feed. The two variations of buying two-tooth ewes and five-year-old ewes save a lot of feed and drop the profit substantially. There is quite a lot to consider here.

The right hand column is an example of the benefit to a farmer buying ewe lambs, mating them (as lambs), lambing them, then selling as two-tooth ewes. It is quite profitable.

Deer gross margins

Gross margins make sobering reading and reflect sector concern about the future of venison farming in New Zealand. Breeding, particularly where replacements are bought, is not going to get much support on high-quality country, particularly where irrigation gives farmers other options. However, where farmers can afford to, they may continue to breed due to concerns over availability of quality weaners or environmental restrictions. Trading to finish at 11 months is a little better, but does not yet stack up against lambs, dairy heifers, wintering dairy cows, or bull-beef systems. Buying replacements does not help, and it looks like the place for breeding hinds for venison is on the hills and rough feed. In addition to simplifying the breeding programme, buying replacements reduces the need for breeding stags.

Breeding cow gross margins

The breeding herd (beef) group of gross margins shows three options for selling weaners, i.e. breeding own replacements, buying in-calf heifers or buying mixed-age cows. There is little variation in the four gross margins/kg DM results, however, there is a significant reduction in feed consumed where replacements are bought in. The right-hand column illustrates the effect of wintering breeding cows off with the efficiency per kg DM eaten the same, and a saving of 200,000kg DM of feed.

Bull trading gross margins

Trading margins steers, lambs, heifers and dairy cows

The final two tables illustrate gross margins from more profitable enterprises, which could be substituted for the livestock removed when replacements are either bought or grazing off is used (replacements and/or capital stock).

In summary, the numbers presented here are obviously subjective and each farm will have its own set of relevant performance parameters and costs.

What is important is the approach and the discussion, culminating in a whole farm budget. The benefits from buying replacements are not always immediately obvious, or understood.

- Tom Ward is an Ashburton-based farm consultant.