Set-stocking the flock

Say Waiouru and we automatically think 'army town', but just down the road on the North Island’s Central Plateau, a couple is gaining top sheep fertility and growth rates in a tough environment. Tony Leggett reports.

Waiouru farmers Derek and Leanne White are proving that set stocking their flock almost the entire year delivers consistently strong sheep performance.

In their 2021/22 financial year, their management produced a 153% survival to sale outcome from their two-tooth and mixed-age ewes, and a 91% result for their mated ewe hoggets.

Their net income from sheep for that year was $180/sheep stock unit, nearly $10/ssu above the average for the top 25% of similar class farms compared through the BakerAg FAB analysis that year.

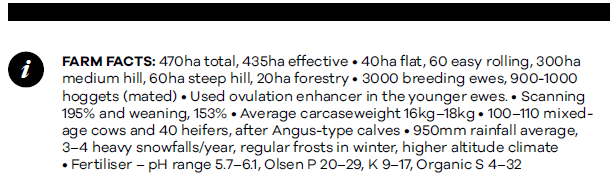

The Whites farm 3000 breeding ewes, split at mating time into a B flock of about 1000 mostly older and poorer constitution ewes mated to Poll Dorset or South Suffolk rams. They are mated two weeks ahead of the maternal A mob of 2000 mostly Romney ewes, which start lambing from September 20.

Most of the six-tooth and five-year-old ewes are quarter-Texel, quarter-Coopworth ewes.

“The original genetics we started with were highly fecund but weaned small lambs and had low growth rates, so we introduced some composites to improve on this,” Derek says.

The composite rams they used produced meaty lambs and had good first-cross progeny, but then they began to lose fertility and started to see constitutional faults in the young sheep.

“We realised we were on the wrong track.”

Derek says that’s why they moved to Wairere Romney rams to straighten everything back up and give them the fertility and growth rates they were after.

“The rams we get from Derek [Wairere owner Derek Daniell] are certainly delivering that.”

Scanning percentages are returning to 190–200%, but to boost fertility over the 2021 and 2022 matings the Whites used the ovulation enhancer Ovastim in their younger ewes.

Scanning jumped from 168% the previous year to 195%, a pleasing outcome when lambing percentage is the single biggest contributor to profitability in a breeding system.

They chose not to do the two-tooths last year just to see where they naturally were. They scanned 190%.

“There’s a good 20–25% increase in two-tooths’ scanning percentage from using Ovastim, so where there is a genetic deficit, it’s well worth the money spent.”

Stocking rate for the farm is high for the altitude and contour at 12.1su/ha wintered (based on 1 ewe = 1su). The Whites believe in putting pressure on their sheep to help identify the best performers and cull heavily any repeat poor performers.

A weaning percentage of about 150% is optimal for the farm.

Derek says it has averaged 149% over the past seven years and been as high as 155% twice in that period.

“I’d rather avoid too many triplet lambs and run a higher stocking rate as this will always deliver more lambs per hectare.”

Aside from a short period leading up to mating and the first cycle, the ewes are mostly set stocked and shuffle grazed according to their condition. Typically, 80–90% of the ewes are in lamb by the end of the first cycle, so Derek starts to tighten them up to conserve feed heading into winter.

Using the gate

Using the gate

Regular drafting through satellite yards allows any ewes in lighter condition to be drafted off and run in a smaller mob with less pressure.

“The drafting gate in your yards is one of your most valuable tools.

“It doesn’t cost anything to use and you can consistently draft off any lighter stock as they pass the yards anytime.”

Derek says ewes are a bit like a jet boat. It takes a lot of time and energy to get up on the plane, but once they’re there, so long as they have scope, they seem to be able to maintain themselves on short covers.

He says a lot of winter feed can be wasted feeding fat ewes in a rotation system when the sheep are treated as one group. That feed can be used to raise the condition of lighter sheep within that group.

“If you jam a large mob of varying condition sheep into a small paddock, you soon create a tail of about 20% due to some sheep being less resilient than others.”

Farming at altitude with a high stocking rate requires a different approach, especially to get through the long winter months. It isn’t unusual to get three or four good snowfalls a year and frosts can make winters long and cold.

Derek says they have had snow any day of the year, from putting the terminal rams out early April to Christmas day.

“Five years ago, we had half a metre on the old woolshed roof which collapsed, so that was a bit of a bonus.”

He says they don’t get a lot of regrowth so once the grass is eaten, it doesn’t come back until spring.

Managing feed

Derek admits his feed management approach is more “seat of the pants” than formal feed budgeting. He cut his teeth on steeper hill country farms where there were limited paddocks, mainly larger in size. He learned to match feed demand to supply and keep it simple. The more variable climatic conditions in recent years also adds another layer of complexity.

“It’s easy to get tangled up with numbers, but you’re farming stock, not grass.”

He would rather have fat sheep and no grass, but spread out, than skinny sheep on a rotation with heaps of grass in front of them.

“Sometimes a sheep’s biggest enemy is another sheep.”

The older B flock ewes are unscanned. The A flock ewes are scanned and triplets are identified. These are preferentially fed on pasture (with any tail-end ewes) until they are set stocked for lambing with the twin ewes.

There’s no daily lambing beat for the two-tooths or older ewes, other than picking up the odd cast ewe, but the in-lamb ewe hoggets get a visit at least daily.

Winter kale crops are critical to carrying a high stocking rate through the winter. Timing is critical to yield and having their own equipment helps mitigate some of this risk.

About 2200 ewes will go on to crop for a month to spell the pasture in late winter ahead of lambing, strip grazing the kale behind three-wire electric fencing with a fresh break every two to three days depending on weather.

“You can waste a lot of crop in bad weather or when it’s wet, so we usually have a grass paddock alongside any crop to spell it if the weather turns.”

Between 900 and 1000 ewe hoggets are mated from May 10 and lamb on the farm’s flat and easier country. This is the most exposed and south facing, so hogget lambing percentages can vary greatly depending on southerly weather patterns.

They operate a high replacement rate close to 30%, but it means two-tooths can be culled hard if they don’t catch back up from lambing. This requires grazing out between 100 to 150 dry hoggets to replace deaths and maintain numbers each year.

All ewe hoggets are given the chance to get in lamb to about 20–30 homebred terminal ram lambs left entire for the purpose.

The Whites aim to wean the terminal-sired lambs pre-Christmas and kill half-prime off their mothers, even if that means killing down to a lower carcaseweight. Minimum weight at weaning for slaughter is 34–35kg liveweight, depending on the lamb.

Average carcaseweight across the season is typically between 16kg–18kg depending on season and if any store lambs are sold.

“There’s a lot of winter traders chasing autumn lambs these days, so we’re not too hung up on whether they go prime or store,” Derek says.

“The main criteria is dollars per head and there seems to be a point now where you can dump a lot of lambs that are 5–8kg lighter than works schedule in the autumn for a similar price.”

The second half of their terminal lambs go on to Pasja and are sold prime. Derek also aims to draft 25% of male lambs in the A flock prime at weaning to minimise the number that require shearing. “We typically shear about half of our lamb crop.”

Their usual mean kill date is January 25 but they had to play catch up this year by adding more carcaseweight to lambs to get the dollar outcome they were targeting for the second half of the season.

The Whites have used drench capsules extensively for many years. One year they trialled not using them and had to put a lot of weight on their ewes to get them back into shape for mating. It wasn’t ideal in the dry summer that prevailed.

They regularly monitor for resistance to drench-active ingredients and have deliberately run a large number of ewes without capsules to create the refugia mob, known to reduce the onset of resistance.

Sorting the cropping

Crops and new grass are crucial to maintaining the high winter stocking rate.

Using mostly their own gear, the Whites have been cropping and re-grassing up to 40ha each year.

About 15ha of Regal kale grown annually allows 2200 mixed-age and two-tooth ewes to get a month off grass in late winter, allowing lambing paddocks to freshen up ahead of the due date.

Ewe hogget mating performance and sale lamb finishing to target carcaseweight are underpinned by 5–10ha of Pasja and 10–15ha of new grass, depending on the paddock rotation. They have used swedes in the past instead of kale for extra tonnage, but Derek believes they don’t deliver the same high protein forage for ewes pre-lamb.

The wet autumn this year created some challenges for returning summer crops back to new grass and also impeded growth of the kale crops. However, the moisture delivered a growthy summer and early autumn so the Whites carried more feed into winter than normal to cover the loss from their poorer kale crops.

Their new grass cultivar preferences are Rohan ryegrass and clovers on the steeper paddocks and Shogun and clovers on the easier top country.

Costs to establish the kale crops have increased but Ruapehu Farm Supplies agronomist Tane Knight recently prepared a gross-margin analysis for the Whites that showed it was still a cost-effective choice.

It showed a 10 tonne/ha crop was costing 10c/kg drymatter (DM) but had increased this year to 13c/kg DM. An 8t/ ha crop now costs 15c/kg to establish.

He says crops are the cheapest form of winter feed for the Whites, when compared to putting on nitrogen with a truck at 19c/kg DM and summer crops now up to 20c/kg DM.

They’ve completed one rotation of suitable paddocks on the farm, starting with the steepest slopes first and moving through the easier country. All crops are sown with 250–300kg/ha of Cropmaster with Boron boost. The Whites are also making a transition to reactive rock phosphate (RPR) for their maintenance fertiliser and this will be applied in the autumn. Some of the change is price driven, but there is also a genuine shift to minimise nitrogen use at scale after they had previously applied DAP in the spring.

Their plan is to apply an RPR-superphosphate blend for two years to transition to a full RPR product in following years. This year they plan to reduce the phosphorus (P) component back to 18 units/ha to shave a little off the cost and allow fertiliser prices to settle down a bit.

All their new grass and balage paddocks get 230kg/ha of potash/DAP/Sup (26:30:60:34). All crops are sown with 250–300kg/ha of Cropmaster plus Boron boost.

Dickie Direct territory manager Zara van Hout says the rainfall level and pH of soils suit the use of RPR on the farm.

She says P levels range from 20 to 25 and will support the transition to RPR over time. To overcome the soil’s natural sulphur (S) deficiency, extra S will be applied with the maintenance fertiliser.

Derek says the move to RPR should reduce the risk of nutrient run-off in high rainfall events in the first 100 days after application because it is less soluble than superphosphate.

“It compares favourably with superphosphate in terms of unit cost of P, and we feel this is a great mitigation tool to reduce nutrient loading on our waterways too.”

He’s also hoping the RPR’s small calcium carbonate content will offer some reduction in liming costs in the future. (See more on RPR p80)

The Whites have also been embracing Ravensdown’s new spreading technology, HawkeEye, which helps top dressing pilots and ground spreaders keep fertiliser out of sensitive areas, particularly waterways.

Improving water quality

The Whites are part of the Rangitikei River Catchment Group, set up to encourage community involvement in projects to monitor and enhance water quality.

“It’s a good concept. We all want to see the waterways improve in quality so we’re building up our own data set, doing nutrient budgets and investing in projects that we think will make a difference.”

They have been involved in Horizons One Plan initiative for the past decade and have completed 5km of fencing along waterways and stock exclusion zones, retired 5ha of native bush and established three wetland areas.

The Whites believe all this extra work enhances the aesthetic properties of the farm for future generations and gives them credibility around their social licence to farm when faced with criticism. They are also hoping it helps educate the non-farming voting public.

Poplar planting on high-risk areas has also been completed in the past decade, along with scattered planting for soil stabilisation and shade for livestock.

Teamwork is crucial to the success of Derek and Leanne White. Both have full-time roles on the farm and share equally in most of the farming activities. Working as a team means the operational and financial management of the business is shared between them, creating flexibility around workload and family commitments.

It also has the added advantage of minimising the need for outside casual labour with most of the farm tasks such as fencing, cultivation, and development work completed in-house.

Their farm White Ridge is 470ha (435ha effective) of hill country just south of Waiouru. It was originally farmed as two similar sized blocks, one by Derek’s family until his parents bought their neighbour’s farm in the late 1980s following the withdrawal of subsidies.

Derek’s passion for a life in farming included two years at the renowned cadet training school at Smedley in Hawke’s Bay, followed by shepherding around Wairarapa, Hunterville and Taihape areas before heading to Lincoln University in 2002 to complete a Diploma in Farm Management, graduating with Distinction the following year.

After Lincoln, Derek managed a 2000ha block near Hunterville for four years, then spent a year in North America driving trucks and working on cattle feedlots and ranches.

Leanne grew up on a sheep and beef farm near Masterton. She completed a Bachelor of Nursing degree in 2005. She worked at Palmerston North Hospital in the fields of medical, surgical and emergency nursing, followed by a short stint working in Australia. After meeting Derek she made the move to the Rangitikei and began working at Taihape Health, in practice and district nursing roles, and on her days off helped out on the lease block she and Derek had just acquired.

The ownership goal

As a couple, they were determined to get into farm ownership from the outset. Their plan began in 2005 with buying a 2.5ha block of land in the upper Pohangina Valley. They sold this in 2008; a good stepping-stone towards buying the stock and plant for a 150ha lease block at Mangaweka that they leased for the next six years. The couple say having debt at a young age was a great motivator and a good compulsory saving scheme.

They added leasing the 470ha home farm from 2010 to 2014 and managed to pay off the stock and plant debt over that four-year period before buying the property in July 2014 and relinquishing the Mangaweka lease at the same time.

“We were fortunate to have an opportunity from my parents to farm the home property, but this would never have been realised unless there was a well-devised plan and significant capital brought into the equation,” Derek says.

Their farm succession plan began after meeting with succession specialist Phil Guscott at a local Beef and Lamb Day. After listening to Phil’s seminar a couple of times, and with a bit of gentle persuasion from Derek, Phil agreed to be involved.

“What Phil said in his seminar was a bit of a lightbulb moment for me.

Derek says they had to get him involved. He was instrumental with his experience and advice.

“This would have to be some of the best money we’ve ever spent.”

The past 10 years have mainly been about debt consolidation and development of the farm asset, as well as bringing up their three children (James, 11, Kate, 9 and Jess, 4).

A more recent goal they’ve achieved is asset diversification, including investing in property off the farm to diversify income streams and provide equity for their own farm succession.

“This has had the added benefit of significantly improving our work-life balance as well,” Leanne says.

Useful networks

The Whites also rely on their wider networks, particularly their farm accountant Trevor Young and ANZ banker Scott Mitchell.

Derek has always supported discussion groups and feels the opportunities to engage with similar-minded farmers who offer honest appraisal of a farm business and its management is beneficial to their success.

“I find the discussions are awesome and I’m always asking questions and looking for feedback and knowledge.”

Derek also got a taste of the power of benchmarking and discussion groups while working in the Wairarapa and was determined to link up his farm’s data to see how it compared.

The Whites were keen participants in the establishment of a local Red Meat Profit Partnership discussion group because they knew the power of peer participation. It has been providing financial data so that each farm can benchmark itself against others in the group. “For a cost of $400–$500 a year, this is a powerful tool.”

Derek says by learning to analyse the data, a farmer can build a picture of an individual’s businesses strengths and weaknesses and where their potential opportunities may lie.

The feedback from the judging of the previous year’s Red Meat Farmers competition, when the Whites were runners-up, was also very powerful. Leanne says intentionally working on the business, not just in the business, was a key take-home from the earlier competition judging session.

“Time off the farm to reflect on goals was another,” she says.

That means booking holiday dates in advance and sticking to them.

Cattle sale policy changes

The Whites have been fine-tuning their cattle enterprise over the past few years with a shift in bull genetics and sale policy for progeny.

McFadzean Meatmaker bulls are the sire choice for the Whites’ 100–110 mixed-age cows, but they are now selecting more compact traditional Angus-type bulls after earlier buying bigger Simmental-Angus bulls that delivered impressive growth rates in their progeny but increased frame size in their heifer progeny.

Derek says the more compact black, Angus-type calves are also proving popular with store market buyers.

Between 30 and 40 rising-two-year heifers are mated to a low birthweight Angus bull and calve behind a wire. Any dries are finished and sold to the domestic beef market.

Calving in the main mob starts from October 15, spread among the ewes in their lambing paddocks and coinciding with the usual spring flush.

They had previously sold their sale calves at weaning, but with a mean calving date of mid-November they decided to sell later. Their male calf crop now leaves the farm as yearling steers after a winter break-feeding on the flats and supplemented with home-grown lucerne balage. This gets them to about 300kg liveweight by early spring.

“The spring market can be very fickle, and it only takes one poor large sale for the whole market to fall over. This can also work in reverse if it is a grass market,” Derek says.

“If we can get a $400 margin from weaners to yearlings in wintering them, then we believe that this delivers a good margin for the work involved. It also makes sense for us with our later-born calves.”

They are also experimenting with keeping between 15 and 20 of their male calves and killing them before the second winter. The terminal genetics have helped with this.

From 60 heifer calves born each year, 50 go to the bull as yearlings and typically 45 scan in-calf.

In their 2021/22 financial year, their cattle delivered net income of just under $100/cattle stock unit.