Seeking a better-balanced bull

Domestication of cattle may be the cause of bull breakdowns, vet Dave Robertson writes.

Domestication of cattle may be the cause of bull breakdowns, vet Dave Robertson writes.

From the pregnancy testing I have done over autumn, bull soundness issues are often a common contributor to the poorer results. Bull issues are most often suspected when other key parameters are optimised, such as cow condition and previous year calving was not spread-out.

As part of the follow-up to poor results, I spent most of April/May service testing commercial bulls and doing insurance jobs. During this process conversations often end up on the topic of why bulls don’t last? It is an interesting question which I have attempted to frame with a bit of bio-mechanics, evolutionary theory and artistic licence.

The most common reasons for bull breakdowns are penile injuries, chronic lower back degeneration and lameness (feet infections and leg injuries). Penile injuries are the most common insurance claim.

- The average service lifespan for a beef bull is three seasons (five years old).

- 45% of unsound bulls go out for another season.

How did we get a situation where we cannot cull bulls on production-based reasons and it is usually replacement of injured bulls that is required?

If we were to select for longevity, what do we look for in the appearance of a bull or the breeding values to indicate it will last?

I am not entirely sure of the answers but it is an interesting topic to debate with experienced cattle breeders. What follows are a few broad concepts of what happens in nature that may explain some of the dilemma of bull breakdowns.

The physics: Cattle have got bigger

A one-tonne animal throwing all its weight in the air and forward attempting to thread a bit of fibro-elastic tissue through a small target (without looking) is bound to cause some issues eventually.

Like the higher injury rate in modern super-rugby players compared to the amateur era, it appears the injury rate in bulls has increased as they have gotten bigger. It has been observed that leaner commercial bulls (of the same genetics) have lower injury rates than fatter, heavier bulls, so there must be something in the more-weight, more-problems theory.

But I don’t think it is just a size issue. The original wild cattle were much bigger at about 1.8-metres tall. There are some geometric things that have occurred in our pursuit of more meat and a certain aesthetic that may be interesting to consider.

The geometrics of mating injury risk

With domestication and selection for more muscle we now have squarer, longer animals with more meat (and weight) in the hind quarter.

The bull is required to lift this hindquarter weight and move forward in an explosive movement during mating. It leads then to the argument that with more force and energy required to move heavier hindquarters there is more risk of error or injury.

The domestic cow also has a high tail head setting, to go with its “good top line”, which means bulls have to move their hindquarters further to achieve a mating from potentially a less-stable platform. Looking to nature there are not many examples of ruminants with fibro-elastic penis arrangements that have proportionally square tail heads or large hindquarters.

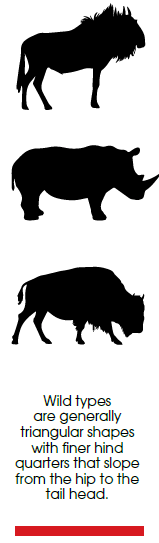

Wild types are generally triangular shapes with finer hindquarters that slope from the hip to the tail head (see the pictures of the wildebeest, the bison, even the rhinoceros). The wild-type female has a more sloping hindquarter angle that would remove some of the angle that the male hindquarter has to travel and also allows the male when mounted to have the centre of balance through the brisket over female rather than through the lower spine in a domesticated bull.

This is all very interesting and maybe somewhat academic, but what can we do about improving the fertility outcomes of our beef herd and longevity of domestic bulls we buy?

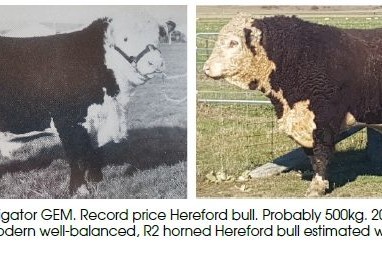

I don’t think most stockpeople could handle selecting “tadpole arsed” animals for the sake of mating efficiency and longevity. But I think we did learn from the 1980s when selecting for extremes of growth, frame size and hip height that bull longevity crashed.

There is no one set way nature designs things, but there is a proportion and balance to all shapes and forms that will lead to better durability than shapes out of balance or over-stressed in certain points.

EBVs have been fantastic for advancement in measurable beef production traits, but they cannot be the total answer to selecting balance and proportion for the physical requirements of efficient serving ability.

Weak neck muscle, lack of masculinity, paunchy guts, straight hocks, loose pizzles, nervous/agitated demeanour, small testicles are all indicators of things that may lead to reduced longevity. It does raise the question as to what dark, unsound shapes we may be selecting by using only artificial insemination of the latest and greatest figured bulls from overseas that we have never seen or even know if they survived past a year…

The ancient Greeks had their guide to the aesthetics of nature in the golden ratio 1: 1.6, closely associated with the Fibonacci number sequence that describes biological growth patterns – fun to look-up for a practical school maths project.

The Greeks and Leonardo Di Vinci based a lot of their art and architecture on that ratio. Perhaps this may be the answer to selecting better balanced bulls with longevity?

- Dave Robertson is a vet with the Veterinary Centre, Oamaru.