Resisting the parasite plague

Despite regular warnings over recent decades, farmers appear unwilling to tackle the issue of drench resistance in sheep. By Lynda Gray.

What does it take to get the drench resistance message through?

Vets and scientists have been banging on for 20 years about the growing tide of internal parasite (worm) resistance to anthelmintic drench among New Zealand’s sheep flock and the dire production consequences that comes with it.

The alarm bells started back in the early 2000s on release of a national survey on drench resistance. Ever since there’s been lots of research around the reasons for and possible answers to the problem but limited success at getting the message across to farmers.

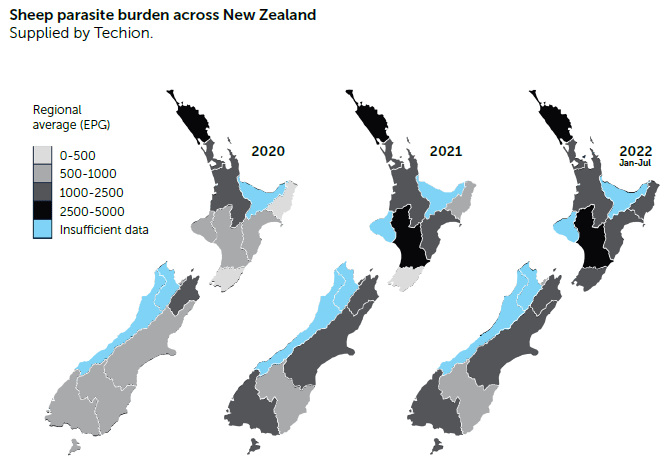

The most recent call out was from Techion (formerly Fecpak) which runs a laboratory processing 30,000 faecal egg count samples annually. It reported in August that unusually wet weather had contributed to record parasite numbers in sheep across the country this winter.

The July average was 784 eggs per gram (epg) compared with 607epg in 2021. Some counts in South Island flocks were more than 3000epg, and in the North Island 1200epg.

Techion managing director Greg Mirams, said that in general, sheep with FEC counts of more than 500epg would be under stress from parasites and likely suffering a drop in condition.

“Worm burdens are as high as they’ve ever been and that’s partly reflective of climate change and is something the industry needs to address,” he said.

Vet and regular Country-Wide columnist Trevor Cook said farmer failure to pick up and act on the warnings was a train wreck waiting to happen.

“Farmers can’t see it coming and by the time they realise their drench is becoming less and less effective it’s too late.”

He likened the attitude to the 5+ A Day campaign aimed at upping the daily human consumption of fruit and vegetables.

“We all know what we should be doing but we don’t and the consequences of not doing so only become apparent when it’s too late.”

Reaching for the drench gun was almost embedded in farmer DNA.

He saw examples time and time again such as the client who put the effort into building an integrated livestock system to alleviate the worm risk but decided to blanket drench all the lambs anyway. A faecal egg count had shown there was virtually no worm challenge; drenching them was a waste of time and money and more than likely feeding was the cause of the poor weight gains.

Another example was the farmer who bought a farm on which a faecal egg count reduction test (FECRT) had revealed a very low level of drench resistance. However, the farmer called Cook in the lead up to the first lambing asking for advice on the best long-acting drench to use.

Brick wall moments like these frustrated him but there were some signs of positive change with a few of his clients taking on board management and genetics to reduce reliance on drench.

There were three tools for control he said:

- Drench

- Management

- Genetics

Drench had been the go-to tool for the last 50 years, but it should be the last resort. Management, such as integration of stock classes, long grazing rotations, the use of crops and grazing plans, was the big opportunity.

“It’s the cornerstone of tools, and genetics sit on top of that. The opportunity from genetics becomes more powerful once the worm challenge is reduced.”

Another step in the right direction was the first-time appointment of a manager to Wormwise, a programme he helped instigate in 2005. The goal of the collective backed by Beef + Lamb New Zealand, MPI, Agcarm and the NZVA was to slow the increase in parasites resistant to drenches.

Central North Island vet Ginny Dudonski was appointed the part-time Wormwise manager in May. She’s very familiar with worm and drench resistance and believed there were two main reasons why farmers didn’t understand the problem.

“Humans are wired to respond to pain…with drench resistance a lot of farmers won’t do anything until they feel the pain of lambs not growing or in the worst situation dying.”

Also, there were now successive generations who didn’t know how to farm without drenching.

“Before the first anthelmintic drenches in the late 1960s farmers learnt how to manage the problem. There were fewer intensive systems and lower stocking rates, but they adapted their farm management to cope.”

One of her first priorities was to get practical advice in bite sized chunks to farmers.

“There’s a lot of good and useful generic type research and I see one of my roles as taking those basic messages and showing how they can be practically applied in on-farm examples.”

As well as talking with several farmer groups she was using social media platforms Facebook and Instagram to post videos on specific on-farm management.

Benchmarking the extent of the drench resistance problem was another priority but a repeat of the early 2000s survey would not happen. Instead, diagnostic testing laboratory Gribbles was developing a standardised system for onfarm FECRT tests and database to report trends. This would provide an initial snapshot from which trends in resistance would become apparent over time. Dudonski was also looking at the best way to include sheep and beef test results from other testing laboratories.

Another priority was to revisit a lot of past relevant research which had practical applications but was not effectively passed on to farmers.

There was a lot of work to tick off and in the meantime, there would be more pain before inroads were made into the problem of worm and drench resistance. Dudonski hoped that over the next year farmers would become familiar with the role and goal of Wormwise. Her seven-year goal was that industry and farmer mindset would be around a farm system approach rather than one-track drench gun cure.

Cost and loss

There’s no shortage of research substantiating the loss and cost of drench resistance.

Back in 1982, a 14-week trial by Professor Coop (Lincoln University) showed that the lambs on high challenge worm pastures drenched every 21 days took 44 days longer to reach prime weights than those undrenched on low challenge pastures.

In 2011, ‘The production cost of anthelmintic resistance in lambs’ calculated that ineffective drenching reduced lamb average liveweight gain by 9kg and carcaseweight by 4.7kg equating to a 10.4% drop in carcase value. The effect of reduced parasite control was also seen in a range of other performance variables such as body condition, and dags.

A 2014-2017 study by Techion and United Kingdom supermarket chain Sainsbury, looked at the production hit from ineffective drenching on 59 UK and 40 NZ supplier farms. It calculated an average weight loss per lamb of 3.13kg/ carcase and lost income of $15.18 using the B+LNZ average lamb meat 2016-17 farmgate price of $4.85. In today’s market, using the B+LNZ 2021-22 weighted average farm-gate lamb price of 7.24c/kg, the comparable figure was $22.66.

Mirams said the environmental cost of drench resistance was another cost factor. The 2018 research, ‘Ubiquitous parasites drive a 33% increase in methane yield from livestock’ evaluated methane emissions per unit of feed intake in parasitised and non-parasitised finishing lambs in Scotland. It could be argued that a Scottish feeding system was different to that in NZ but regardless there was a significant difference of GHG emissions from lambs with an undetected parasite burden.

No new drenches

When will animal health companies come up with a new drench was often asked by farmers, Trevor Cook said, and the answer was simple: Never.

There wasn’t the financial return from development of a new drench for ruminant livestock. Instead, it was the companion animal market that was attracting the research spend.

“People are happy to spend $50 on a treatment for their cat but not $5 on a beef steer that will return them hundreds of dollars,” Dave Leathwick said.

In line with this thinking was global animal health company Boehringer Ingelheim’s announcement late last year that they would stop the NZ manufacture of livestock ruminant products by December 2022.

He said NZ was a small and insignificant market in the global scheme of things, and revenue from anti-parasite treatments for sheep even less.

Research ignored

“Soul destroying” was how AgResearch scientist Dave Leathwick described his 30-year career dedicated largely to the research of internal parasites in ruminant livestock.

The winner of the 2016 B+LNZ Sheep Industry Science Award said it was demoralising to have produced the work and data showing how drench resistance could be prevented and have it ignored by most vets and farmers.

“From that perspective I’ve been a miserable failure… there have been a few notable exceptions of farmers who have played the game and they’ve done spectacularly well in both farming and preventing resistance.”

The best hope for worm management was the ‘reversion’ approach or ways to reverse or minimise the harm of drench resistance.

He said it was about changing farming systems so that there’s less reliance on drench. It was still a new line of study so there’s still a lot of unknowns.

“We may be able to make the problem go away but the unknown is whether it will be gone forever.”