Realities of sheep and cattle farming

With its large cattle and sheep populations, a country like New Zealand is dealing with waste from not five million but the equivalent of more than 100m humans. By Ken Geenty.

With its large cattle and sheep populations, a country like New Zealand is dealing with waste from not five million but the equivalent of more than 100m humans. By Ken Geenty.

Sheep and cattle farmers in New Zealand are regarded worldwide as kings of pasture grazing systems. Our clean green image is out there and needs guarding for the sake of our marketing edge. This underlines the importance of carefully monitoring to manage and/or mitigate the impacts animal waste and greenhouse gases have on our environment.

Animal waste

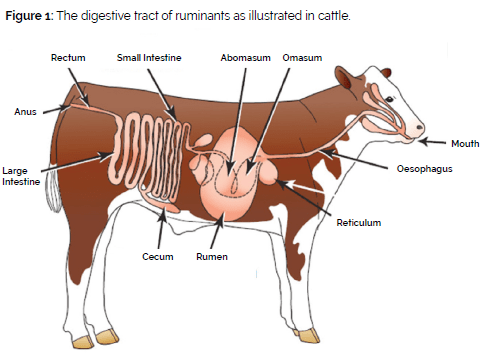

We are one of the world’s most densely populated countries with grazing ruminants. A feature of ruminants compared with humans and other animals like dogs, is the huge size and capacity of their digestive tract. This fermentation vat, consisting of four stomachs as shown in Figure 1, can digest a wide variety of plant products in large amounts. Output of waste mainly as faeces and urine is large.

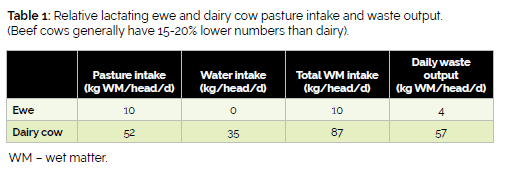

The ruminant digestive tract with its contents is close to 35% of animal body weight with the ability to hold feed equivalent to about 15% of liveweight. For example, as shown in Table 1, a 500kg lactating cow can require up to 52kg of pasture wet-matter a day equivalent roughly to a firmly packed sack of grass, plus drinking about 35kg of water.

Adult ewes in comparison eat about 10kg or a sugar bag full of tucker daily. Cows consume proportionately much more water than ewes so have a larger wet-matter waste output. On the other hand sheep more efficiently spread smaller dollops of waste around the paddock.

Trends in the NZ livestock industries over the past couple of decades have shown a dramatic increase in dairy cattle numbers reaching just under 7 million. During the same period beef cattle have declined by some 12% to 4m and sheep by 32% to 26m. Intensive dairying has moved into many of the former sheep and beef farming areas.

The above numbers are large by world standards. For example, with a population of 5m, we are about the same size as the state of Colorado in the United States, but with about 20% fewer people. However Colorado has a dairy and beef herd of only 120,000 animals. NZ’s total of about 11m cattle is just over 90 times larger.

Scientists generally agree the waste output of a cow is equivalent to about that of 14 humans, so a country like NZ is dealing with waste from not 5m but more like the equivalent of over 100m humans. And that amount of waste can be a heavy load on our environment.

The main impacts of animal waste are leaching or runoff of nitrogen to groundwater and waterways and pollution with faecal material.

Unfortunately, little can be done about reducing waste from sheep and cattle apart from lowering numbers through diversification. However, some grazing practices such as intensive use of winter crops or break feeding can increase leaching of nitrogen raising soil N loadings as can over use of N fertilisers.

The best move is to consult your rural professional as there are tools such as Overseer which can predict N loadings under different scenarios enabling remedial action.

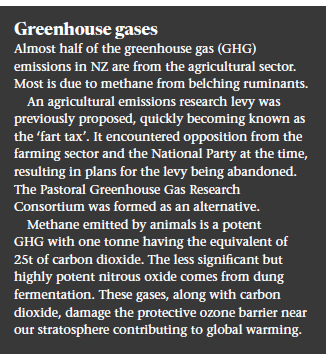

Sea level rises and adverse weather events are some of the well-known consequences of resulting climate change.

A farming-based New Zealand Emissions Trading Scheme to reduce and mitigate effects of GHGs is growing. For carbon credit rewards farm forestry needs to be specifically for greenhouse gas mitigation and not as an eventual cash crop.

Longevity ranges from 50 to 100 years for pines, cypresses, eucalypts and natives. Costs include initial preparation and planting, an initial start-up fee, maintenance including pruning, thinning and fencing and annual returns to MPI.

The long-held view that greenhouse gases from livestock farming make a major contribution to climate change is being questioned. A recent study at the Auckland University of Technology has found that up to 90% of GHG emissions from farming are absorbed by woody trees on or in proximity to farms.

The notion of carbon neutrality simply means that total CO2 gases, or their equivalent, emitted are cancelled out by the same amount of absorption. In this case GHGs are gobbled up by growing woody trees and incorporated via photosynthesis to plant storage.

The insatiable appetite of trees for carbon is highlighted in a Nature Journal article on climate change. It pointed out that our native forests, often adjacent to farming areas, are an enormous carbon sink. Nationally they hold some 7 billion tons of CO2 that would normally be in the atmosphere. This GHG storage by our native forests is equivalent to 86 years of NZ’s total emissions.

Therefore, although much of our slow-growing native trees are not eligible for the carbon trading scheme they collectively make a very significant contribution to GHG mitigation.

Not surprisingly tree planting on farms is gaining momentum. Of 8.5 million hectares of sheep and beef farms it is estimated the 1.7 million ha in trees will grow to 2m ha by 2028. Areas planted can include retired areas on farms or at least 30 metre wide riparian strips protecting waterways. With 42ha of growing trees mitigating equivalent emissions from 100 dairy cows or 500 ewes, large-scale plantings are needed for meaningful GHG mitigation. This could well change the face of our hill country farms.

Some argue a large proportion of these plantings are pine monocultures, sometimes with detrimental environmental and farming consequences.

Under the 2015 Paris Agreement our Government pledged to reduce greenhouse gas emissions by 30% below 2005 levels by 2030. An Independent Climate Change Commission (ICCC) is working towards NZ-wide carbon neutrality by 2050. Legislation which should be in place by the end of this year is labelled by Prime Minister Jacinda Ardern as ‘ground-breaking’.

Some practical alternatives for reducing emissions according to a Biological Emissions Reference Group (BERG) include reduced stocking rates with increased per head production, lower fertiliser applications and once daily milking of dairy animals. BERG say sheep and beef farms have made a good start with 30% reduced emissions over the past 25 years.

More information about strategies to reduce GHG emissions on farms can be found on the B+LNZ website at – beeflambnz.com/search?term=greenhouse+gases