Proposal not cautious enough

The Government has released its proposals for agricultural emissions charges as part of climate change mitigations. Joanna Grigg reports on the proposals and their conflicts with the industry’s He Waka Eke Noa suggestions.

The Government has released its proposals for agricultural emissions charges as part of climate change mitigations. Joanna Grigg reports on the proposals and their conflicts with the industry’s He Waka Eke Noa suggestions.

On the table from the Government is a proposed scheme for agriculture. It puts a cost against every sheep, cattle beast and deer on the farm each day, based on their gas output. Farmers are expected to start paying this cost from 2025.

It aims to reduce methane emissions on farms, by 10% by 2030. According to Prime Minister Jacinda Ardern, it will “carve out a high value space for our exporters”.

Nicky Hyslop, South Canterbury farmer and Beef + Lamb NZ Director, says there may be some validity in this claim, long term.

“But our sector must be viable in the short and medium term and changes the Government has proposed to He Waka Eke Noa, puts this at risk.”

“We cannot accept this proposal as it stands.”

Commitment to reducing emissions is important for access to markets, she says, and for multinational customers like McDonalds and Nestle, but it may not attract premiums in the short term.

She thinks the scheme should deliver moderate emission reductions that reflect warming impact, while allowing farms and rural communities to be sustained.

“The Government proposal on the table and their modelling, clearly shows this will not be achieved and disproportionately impacts hill country farming.”

To ensure, as she puts it, “the guts of our farm communities are not hollowed out” she wants to keep the He Waka model. This is all farm sequestration recognised, ongoing industry involvement in governance, and emission price setting that reflects progress to targets.

“No-one else in the world is doing this, so a cautious approach is critical or we will simply be replacing New Zealand food with high-emissions food which is counterproductive for reducing global warming.”

Ignoring this consultation (closing November 18) and hoping it goes away with a 2023 election is not realistic. Christopher Luxon, National Party, says: “National supports New Zealand’s emissions targets, including reaching carbon net zero by 2050. And that means reducing agriculture emissions over time.”

National’s difference seems to be that they may allow farmers to earn credit for all forms of onfarm carbon capture.

Hyslop says while farmers are rightly frustrated and disappointed, they should not panic.

“All the He Waka industry partners are collectively focused on getting changes to this.”

Tell them: eight cents maximum price

FARMER AND BEEF + LAMB NZ Director, Nicky Hyslop, says the price put on methane must be conservative.

She encourages farmers to tell the Government this by submitting on the agricultural emissions proposal.

“Even the Government modelling shows that at 8c, it will have a significant impact on many sheep, beef and deer farms.”

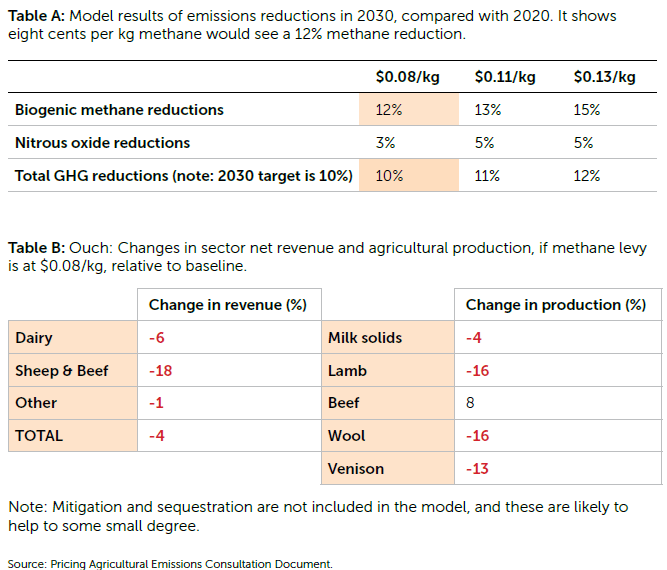

The model in the consultation document shows that 8c by 2030 would reduce methane emissions by 12% (and meet a total 10% target). See Table A.

It comes at a cost. At 8c (Table B) the model predicts an 18% drop in sheep and beef farm net revenue, from 2020 to 2030. This is likely to be made up of a 16% drop in lamb production, 14% drop in wool, 13% fall in deer, and 4% drop in milksolids. Beef production increases in some scenarios, because more cost-effective mitigation technologies are assumed for beef cattle compared with sheep.

The large drop in sheep includes afforestation, the impact of emissions pricing and some farmers switching from sheep to beef, Hyslop says. The Government modelling didn’t include sequestration and any future mitigations, so is a worst-case scenario.

Concern about this drop in production and profitability is the type of comment farmers should put in their submission, Hyslop says.

Farmers may think comments will fall on deaf ears. Hyslop says consultation, along with other actions, are all valid options to get the message across. She suggests making a powerful submission, farmers getting together with neighbours or their catchment group and making a joint submission.

“Describe your farm or catchment, your ongoing commitment to stewardship, your plantings, your estimated carbon sequestration (using the calculator) and the likely emission costs.”

“If we lobby and submit and talk to local and central government, we can be effective and get changes.

“This scheme is the farmers’ scheme, it’s our money being collected and reinvested or paid in sequestration, so they need to listen.”

There are 15 questions to answer in the consultation.

Question Five is the guts of how the levy price will be set. He Waka wanted a committee, including farm industry members, to advise on the price. The Government proposal is for ministers to set the price for both long-lived gas levy and biogenic methane levy.

When it comes to short-lived gas (i.e: methane) the Government wants to set the price based on whether emissions are dropping. This is quite different to what He Waka proposed, which was a price based on just bringing in enough levy to pay for sequestration, a share of administration, incentives to farmers and research into reducing emissions.

The consultation states ministers would periodically assess whether methane emissions were on- or off-track regarding the target. If over- or under-achieving, ministers could update the biogenic methane price. Hyslop says the sustainability of rural communities and local economies must be included in pricing discussions.

“What about the potential loss of rural community, infrastructure, food production capabilities and economic returns – we can’t ignore these in the single-minded drive for overall methane reductions?”

In Section Five there is discussion on ‘pain relief’ for farmers during the transition. The Climate Change Commission had not finished writing specific proposals on what schemes, payments, they might be, so nothing concrete is here. An example may be methane levy relief if an adverse event struck. But the bottom line from the Government is it mustn’t “undermine the intended price signal”.

When it comes to using the levies collected, He Waka recommended levies collected from Maori landowners (e.g: collective agribusiness) go to a dedicated fund and be administered by Maori. The Government proposes to do this by setting a minimum percentage of overall revenue that must go into the dedicated fund.

What’s unclear is how this would actually help Maori-owned sheep and beef farms, especially as they face the same issues of low profitability/hectare and few mitigation options as non-Maori sheep/beef farms.

If Maori levy income comes off lower-stocking-rate land, then the pool of funds is likely to be smaller than average/hectare. The minimum percentage may provide some top-up. In the same way, the sheep and beef industry relies on methane levy payments from intensive dairy to create a pool of funds for sequestration, which is largely on sheep and beef farms.

Hyslop says the Government has tossed out the hard work He Waka did on balancing the different farming partners, and the discussions about wealth transfer using sequestration.

“We need to be careful we don’t divide our sector and tip the scales one way.”

If carbon offsets through sequestration are narrowed, there will be more imbalance.

Question Seven is where farmers need to put their case for pricing.

Hyslop suggests farmers review their numbers and work out the likely cost at the medium-level price of 11c/kg CH4 as this is important for the submission. Some farmers had very high cost estimates as they used the carbon equivalent methane emission tonnes and plugged in the ETS price of $80/ tonne, she says, which is not the right price.

“Eleven cents is a conservative approach and a useful place to start.”

Onfarm exotics out

The freshwater regulation roll-out debacle showed up embarrassing government shortfalls in implementation. This 2022 experience is likely to be one reason behind the Climate Change Commission’s push for pragmatism in designing an onfarm sequestration scheme.

The Government has picked up the vibe and taken pruning shears to He Waka’s extensive work on sequestration recommendations.

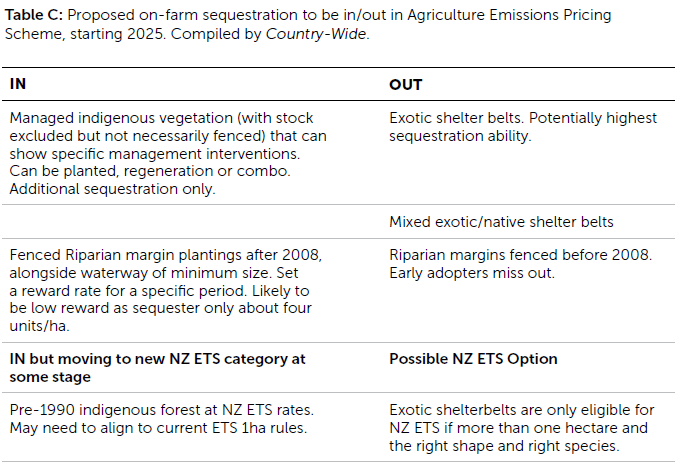

Out go exotic plantings (mainly shelter belt shapes) even though they can’t be included in the NZ ETS, primarily due to being narrower than 30 metres. Managed indigenous forest and post-2008 riparian plantings are in, although size and age and type specifications are undefined. Those early adopters of riparian planting (pre-2008) miss out.

Farmers can respond to sequestration proposals in Question 8 of the consultation.

Nicky Hyslop, Farmer and Beef + Lamb NZ Director, says she has just planted a shelter belt with a mix of natives and exotics. The exotics were chosen to provide faster shade and shelter than less-reliable, slower natives.

“This wouldn’t be counted within ETS farm sequestration as the size is too narrow, yet it couldn’t meet the proposed Government/He Waka scheme as the plant choice is wrong.

“I have issues with the Government promoting wide-scale exotic plantings across whole farms through their ETS policy, when they say they want integrated plantings within working farms, yet don’t reward farmers for it.”

She is also concerned that a figure floated for indigenous sequestration is only 0.5 tonnes/hectare – a very low rate. Riparian vegetation is not known as a high carbon sink. The 2018 Landcare report Carbon Sequestration On Farms, listed riparian vegetation as sequestering about 3.4 tonnes of C02/hectare/year. Exotic woodlots in a shelter belt, for example, would be streets ahead.

This pruning of offset options for farms has raised issues of fairness and has become the most disliked aspect by farmers. Ironically, inequity for non-farming landowners was listed by the Climate Change Commission as a reason for their stance. But isn’t this an agricultural scheme?

The commission suggested creating another scheme altogether – where additional non-NZ ETS plantings could be rewarded alongside biodiversity and water quality. Then, add categories to the NZ ETS.

He Waka had always batted for as much onfarm sequestration as possible, even if it means a gradual addition of categories, with a full scheme by 2027. The original industry He Waka recognised that over time, if the ETS was reformed, this sequestration could be transitioned to the ETS. The Government proposal followed the commission’s approach, and favours the NZ ETS as the home for sequestration. Into this will go new categories like pre-1990 indigenous forest (previously ineligible).

While the bean-counters get this sorted, the Government proposes a short-term option where farmers can take a contract with the government for additional native vegetation, counted from 2025. This would transition, in time, to the ETS. No modelling is provided on whether the contract cost would be worth the offset. An example price is provided of 75% of the NZU price.

After the contract ends, there would be no ongoing liability requiring the vegetation to be maintained as it was for the duration of the contract. The Government shows some vision here, in that the payment could be designed to align with biodiversity incentives being developed.

Farmers with pre-1990 forest may like the idea of an ETS category being opened for them. They will likely get higher payments per hectare via the updated ETS, than discounted rates through the ag emissions scheme. This reward for managing pre-1990 indigenous forest onfarm as a carbon sink, has been a long time coming and will be welcomed. However, farmers don’t have a lot of confidence in NZ ETS recognising regenerating onfarm sequestration.

Any new categories will have to prove themselves to be workable for farms.

The early-movers on riparian fencing and planting (pre-2008) are disadvantaged by the proposed 2008 cut-off. The cut off is because satellite imagery was better from this date. Other methods of proving planting are not discussed.

In 2022, Country-Wide drew attention to problems with the initial HWEN proposal that required full stock exclusion via fencing to get sequestration status for an area of bush/forest. This didn’t recognise that natural boundaries could exclude stock. The new proposal is far more realistic, defining stock exclusion to “include fencing, geographic boundaries and/or dense vegetation that stock cannot access”.

Beef + Lamb NZ said, in their initial email to levy-payers after the proposal release, that there is a lack of detail on sequestration from the Government (including what the sequestration rates could be) and they will be pressing for additional information and clarity over the coming weeks.

DairyNZ strongly disagrees with some of the changes made to limit the recognition and reward farmers will get for their onfarm planting, by removing classes of sequestration like shelterbelts, woodlots and scattered trees.

MfE and MPI will host a webinar consultation on the topic on Wednesday, November 9.