The primary sector’s contribution to the country is far more important than other sectors including tourism because exports will bring wealth and economic recovery from Covid-19. Economist Ray Macleod explains why.

Let’s be clear about three things. The primary industry sector dwarfs the tourism sector. Its supply line to its markets is and will remain far more robust than that of the tourism sector. Primary industries will remain the most important group in the NZ economy and will lead our recovery, post Covid-19.

Forget the comparisons within the gross domestic product (GDP) numbers, what matters is export receipts. Exports drive our wealth growth and our ability to service our domestic and consumptive needs efficiently, in the modern world.

Tourism has been touted as our biggest export earner. It was not, never was, and never will be.

Statistically a case for such a claim can be made, but the real money was always on the primary sector. Such claims were often supported by creatively dividing the primary sector into its contributing component parts and then giving unchallenged air to urban myths around the decreasing importance of the primary sector components, as a percentage of GDP.

An examination of New Zealand economic history (John Singleton, Victoria University) suggests we needed access to the London capital market in the 19th century, to invest in enduring economic activities and early adoption of evolving technology, such as refrigeration – an economy-changing example. We still need access to those global capital markets. We cannot, economically, self-isolate.

Voyage tapped new wealth

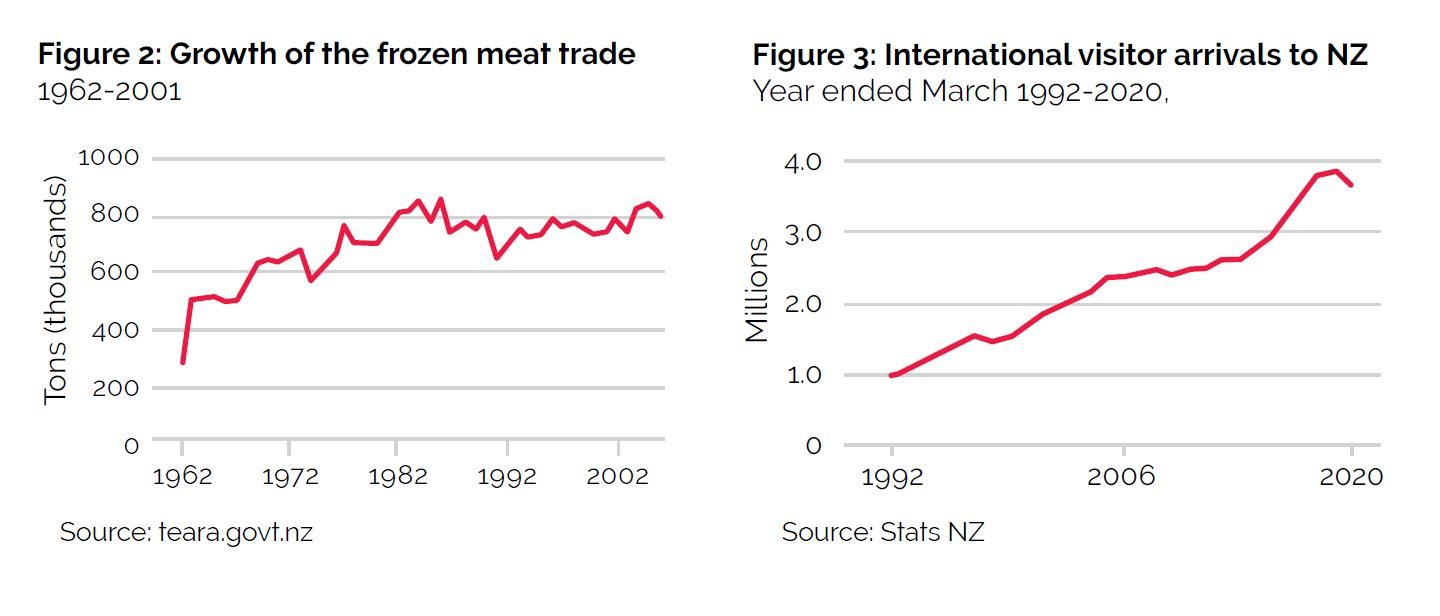

When the SS Dunedin successfully arrived in London in 1882, it opened up a new market and lifted NZ’s wealth. Refrigeration allowed NZ to leverage farm investment and enter the perishable commodity market.

This was unavailable to NZ prior to refrigeration, just as aircraft provided the means to feed the international tourism trade, refrigeration was the link to feed Great Britain’s workers. It provided a robust transport artery for sustainable economic growth.

Unfortunately, every time the world or regional economies hiccup, such as the Asian Economic Crisis of the 1990s, tourism in NZ takes hits. It appears overly sensitive to economic and political instability, and threats to personal safety and welfare, more so than the ever increasing global demand for quality food sources.

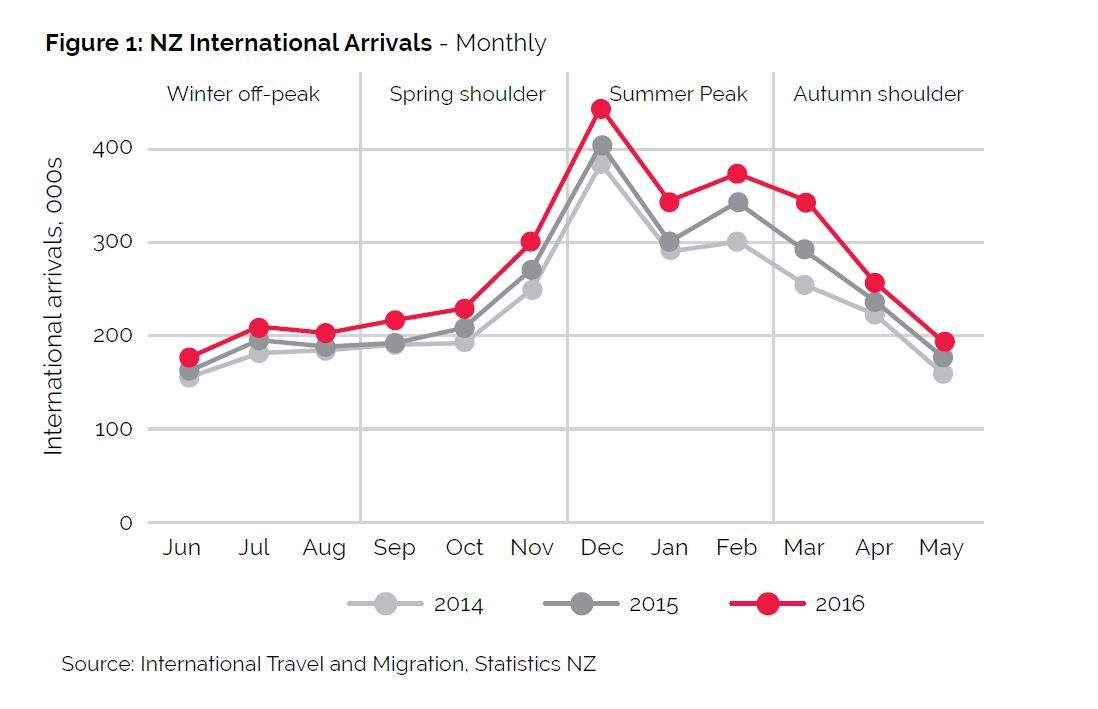

The graphic illustration of international visitor arrival growth in Figure 1 shows just how strong it was as airfares got relatively cheap and vast numbers of people in the Asian middle class prospered.

The impact of the Asian Financial Crisis (1997 to 1999) and the Global Financial Crisis (2008 to 2013) is evident and although significant in tourism terms at the time, will bear no resemblance to the scale of the Covid tourism crisis. We are in for a rough ride.

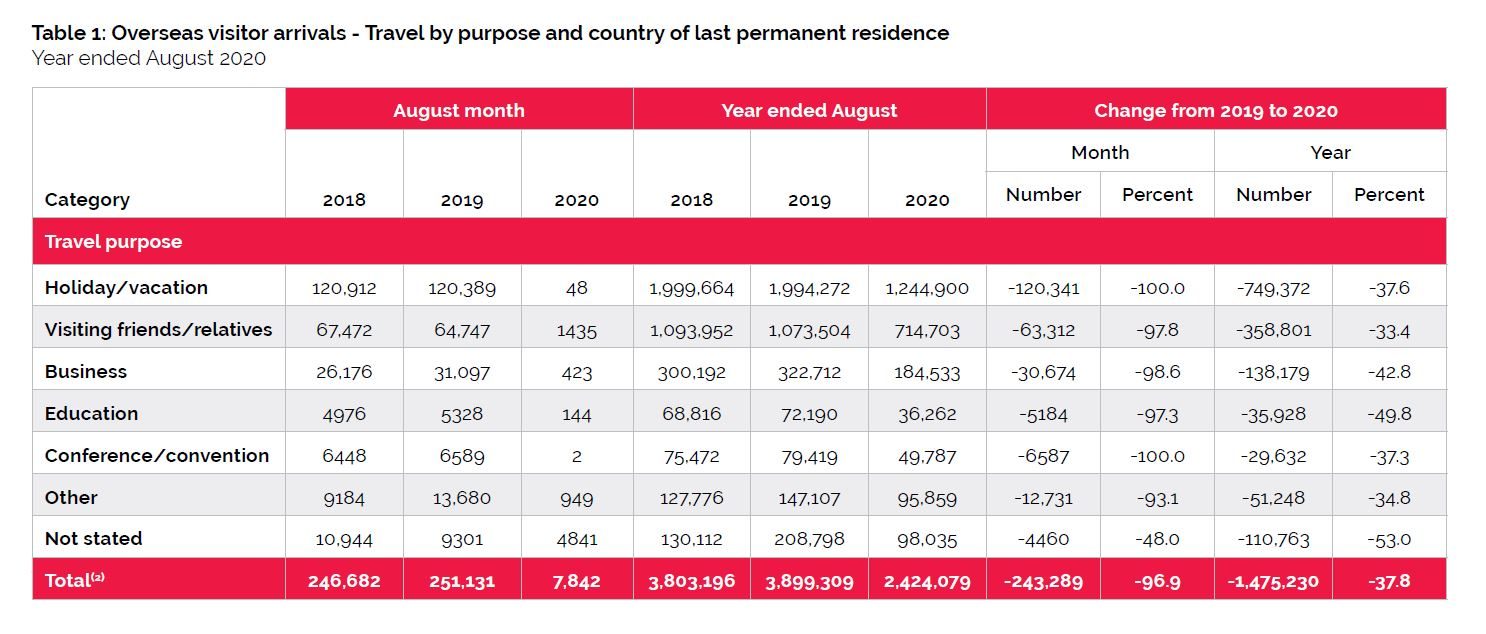

The impact of Covid on tourism is catastrophic. The Stats NZ returns for the year ended August 2020, as reported in Table 1, are staggering. International tourism has been wiped out. We will get a bounce, but when and by how much?

Only 48 international visitors reached NZ in August 2020 compared to 120,389 in 2019. This equates to a $550 million revenue loss for the month, at the average spend of $4665/tourist. Based on last December’s figures tourism will forgo $2 billion in revenue for that month, this year.

The primary sector and an external trade focus are musts for positive economic, welfare and health outcomes. Maybe even political stability.

The data indicates almost half of NZs international arrivals in the 2019 year were not tourists, so how big is the international tourism trade in reality?

Printing money is fool’s gold

NZ cannot afford an inward looking political system hooked on quantitative easing. Printing money is not a solution to combating the hit we are about to take socially and economically. Ultimately printing money is fool’s gold.

Unemployment will rise and our taxation catchment will be increasingly polluted by a combination of unsustainable public spending, the increasing burden of inefficient local and central government, and the loss of economic opportunities. The productive sector will ultimately be NZ’s salvation.

With a growing global population, primary industries produce goods the world needs. Primary produce takes price hits and did so in the 1930s. That was when successive governments interfered in the economy by introducing import restrictions, leading to an extended period of poor investment signalling. This saw investment in industries unsuited to NZ conditions and its small domestic market. Investment which was unsustainable, and dragged the country into a long slow decline, in terms of world economic standings.

In John Singleton’s words “Between 1938 and the 1980s, Latin American-style trade policies fostered the growth of a ramshackle manufacturing sector”. At the same time NZ pursued inward looking economic policies, hindering economic efficiency and flexibility. It forced unwanted and inferior goods on to the public.

If we are serious about addressing poverty in NZ the answer lies with trade (read “Why poverty reduction rests on trade” – World Economic Forum Agenda: March 2019).

We need to grow our share of the world economic pie, to create wealth for our citizens. This needs to be driven by the supply of goods that are sustainable, economically, socially and environmentally, and supported by a robust delivery system. One that, unlike tourism, functions in times of global uncertainty, as the primary sector does.

NZ needs to continue to produce goods essential to meeting global market demand at all times, not just the good times. It is possible to establish an argument that the extent of our investment in tourism was unwise and unsustainable economically, at current levels. It is not the panacea the anti-primary industry activists would have us believe.

Primary production is the main driver of our economy. Of our top 10 exports (October 4, 2020: www.worldstopexports.com, Daniel Workman) only one non-primary sector activity, machinery including computers, makes it at No8, at US$1b. The rest, a staggering 72% of total export receipts are driven by primary sector production.

Enduring external trade pays bills, grows wealth and secures a larger slice of that world economic pie.

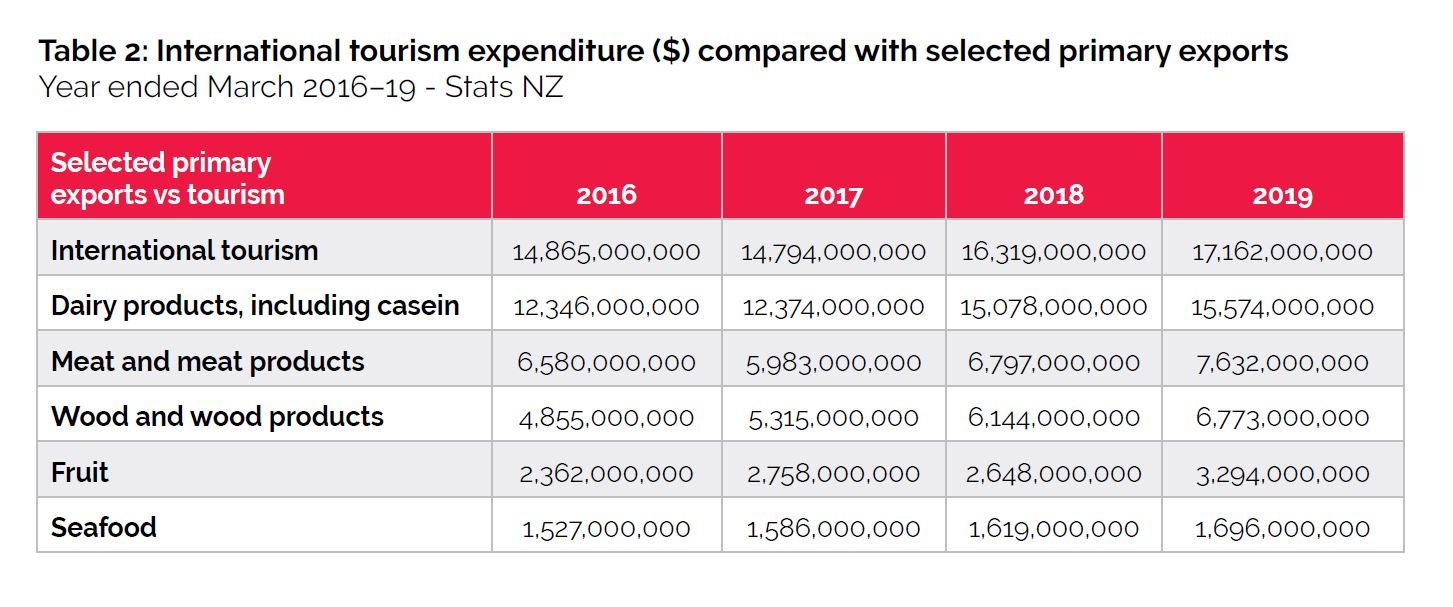

Tourism as a sector is dwarfed by the primary sector (see Table 2).

Add the numbers and “selected” primary exports are $27.67b. Now international tourism is gone. The world is still consuming our food and drinks, wearing our fibres and hides.

Workforce needs to be mobile

Workforce needs to be mobile

How NZ proceeds from here is important. As a nation our labour force is relatively unproductive, with years of state support stifling initiative and drive. It has created a stationary workforce mentality that taxpayers support to stay local and immobile. That workforce needs to flow to areas of opportunity, job growth and productive need.

Tourism is an industry of low wages whose fortunes go up and down with the world economic tide. It is not consistent, reliable and even environmentally unfriendly.

Farming provides access to the most important global market there is, food. Technology and productivity, efficient transport and handling all contribute to constant improvement.

Organisations like Fish and Game have sliced and diced farming into its smallest component parts, for GDP comparative purposes. To divorce its influence upon industries that rely upon it, is disingenuous and shallow. Using GDP figures, ignoring export receipts and expressing the components as a percentage of GDP is a tool of political activism.

Not having the workforce in place to harvest summer and autumn produce will be a major failure. International competitors will fill the vacuum and NZ will struggle to regain the confidence of markets. Selling domestic tourism as a substitute is not a sustainable response but simply a stirring of the money pot.

The result will be public institutions shrinking from a lack of tax capital. Welfare issues will grow as we contemplate a rising falsehood that salvation lies, in varying degrees, on isolationism, tourism, tertiary education and social services.

- Ray MacLeod is general manager of Landward Management, a Dunedin-based company.