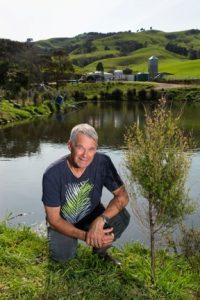

With a ready source of mussel farm waste a Coromandel farmer is looking to cut the aromatic effect on locals while improving soil fertility. Glenys Christian reports.

Coromandel dairy farmer Dirk Sieling believes he can not only reduce fertiliser inputs on his farm but also help remove a waste stream from one of the area’s other important industries. He’s recently bought a Veenhuis slurry injector which he’ll trial this summer.

He was aware of the big Dutch agricultural machinery company’s machines used to reduce odour problems, particularly with effluent from the pork industry. Effluent from barns where cows are housed has also been treated in the same way.

An internet search two years ago found South Island company, FarmChief, was importing the machines and Dirk could immediately see how one could fit into his farming operation. He already has two to three truckloads of mussel shell dumped daily at a high point on his farm from a Whitianga processing plant with strict conditions applied to storage, odour and leaching.

‘We live close to town and we’re aware there might be odour problems if we just spread the material, rather than inject it. We will also be delivering the nutrients at the rootzone and there will be no run-off.’

The former owner of the farm had started the process but Dirk has carried it further, excavating a pond connected to the effluent spreading system below the dumping site to collect any leachate and weathering and then breaking up the shells to put on his races.

With the Veenhuis machine he will be able to handle another waste product from the mussel industry, the marine waste stream produced when the shellfish are removed from the ropes they’re grown on.

“There are sea squirts, mussel beards and small and broken shellfish,” he says.

“The waste is very high in organic nitrogen and other elements.”

It costs mussel farmers to cart this waste to Tirohia near Paeroa to a quarry landfill.

But under the new arrangement the mussel factory will double-grind the waste stream before it’s placed in a coolstore, ready for delivery to Dirk’s farm in one-tonne bags. Once there they’ll be lifted by tractor so the contents can be tipped into an 8000-litre capacity tank on the slurry injector. Dairy effluent will be added and maceration takes place before the mix is injected into the soil through a set of 16 spring-loaded injectors.

“It has to stay suspended so it needs to be kept stirred up on the way to the paddock where it will be used.”

Trials will be on the flat and easier country on the farm’s milking platform, to monitor the stream of nutrients injected into the ground. Dirk’s major concern is any rocks which he hopes won’t prove an issue for the injectors. It is equipped with a pneumatic shut-off valve so the operator can have absolute precision when it comes to injection sites. And it can be connected to GPS, although Dirk’s doesn’t have this at present.

“We want to specifically use it on paddocks which we’re going to crop,” he says.

The idea is to return to maize cropping which they used in the past before swapping to sorghum, of which Dirk is a fan, and millet along with the usual 20 hectares of chicory. They lease 26ha of airfield nearby where they can’t graze cows but have made silage. With the slurry injector Dirk believes they could grow maize there rather than just harvesting what he describes as “medium to poor quality silage”.

Changes will be needed to their 3.5 million litre effluent pond so the pump to the travelling rain gun can be remotely controlled, allowing the tanker to be filled at any hydrant to prevent excess travel. Pond capacity is well beyond that required with effluent spread on 80ha, some of which will have the mussel mix injected as well.

Dirk has two other reasons to see what the machine can deliver.

“We live close to town and we’re aware there might be odour problems if we just spread the material, rather than inject it.”

“We will also be delivering the nutrients at the rootzone and there will be no run-off.”

Complaints have been made and petitions organised during the eight years the mussel shell has been dumped on the farm.

“We’re also aiming to reduce our artificial fertiliser use,” he says.

About 300kg of potassic super per hectare used to go on but five years ago AgKnowledge’s Doug Edmeades recommended putting 750kg then 500kg per hectare on as fertility levels crept up. A self-imposed cap of 150kg of nitrogen is in place with between 100 and 120kg per hectare going on in a number of dressings.

“We’re hoping fertiliser use might drop to a half or even a third.”

Some fertiliser inputs will still be needed on the hillier areas.

“If it all works out there will be big cost savings,” Dirk says.

Not only has the price of the slurry injector increased since he placed his order, but due to production processes he was built a larger one at the same price as for a smaller model. And of course the value of the New Zealand dollar has dropped.

Another future option would be setting up a contracting business so local farmers can have the benefit of the machine without the capital cost. And there will be no problem moving the injector between paddocks or properties due to a hydraulic transport lock.

Making comparisons

A recent six-week trip to his birthplace gave Dirk Sieling a good chance to compare the environmental constraints dairy farmers here are facing compared with those in Holland.

“I hadn’t been back since 1974 to see cousins and friends,” he says.

“I was amazed to see cattle on riverbanks and no fences with a lot of paddocks separated by open drains.”

Government-owned cattle, bred to resemble the original wild breeds, were allowed to roam around big lakes made into nature areas, along with big herds of wild Swedish fjord horses.

“No one batted an eyelid. It seemed to be normal.”

But while the Dutch were happy for cattle to roam as they wished there was debate as to whether their numbers should be kept managed or whether they should be allowed to die naturally.

Scottish Highland genetics had already been introduced to the local Heck cattle which looked very similar to the wild cattle of centuries ago.

Dutch dairy farmers who increased herd numbers when European Union quotas came off in 2015 are now reducing them due to nutrient restrictions. And with the northern summer’s heat feed supplies were running low.

“Dutch farmers didn’t want to keep hearing about being subsidised.

“What came through loud and clear was that they realise they have to make an effort to connect with the public because of the rural/urban divide.”

His cousin, who milks 300 cows, and uses their effluent in a biodigester to produce gas which he sells to the national grid, held an open day recently.

“4000 people arrived.

“They were genuinely interested, they want to reconnect with nature.”

Dutch farmers seemed to him to be better off than their New Zealand counterparts in terms of overall income.

“Farm prices are higher and it’s impossible to get a farm unless you inherit one,” he says.

There are the same issues as seen in this country getting young people into farming. But Dirk says a TV programme in which young Dutch farmers seek partners has been a big success and was much talked about throughout the country.

Countering arguments

While farmer awareness of environmental issues has been raised over the last five years, the same progress hasn’t been made with green lobby groups, Dirk Sieling believes.

He wants dairy farmers’ representative bodies to fully embrace what he sees as their dual roles of encouraging farmers along the right path as well as pushing back on what he calls “fake science”.

“Some environmental groups use cherry-picked statistics and the public doesn’t know any better.

“Groups representing farmers have taken the attitude that they want to work with environmental groups and they don’t want to upset them.

“The public would get a different impression because all they hear now is how bad farmers are and there’s insufficient counter-argument from their own bodies.”

Dirk was one of two farmer members of the Stakeholders Working Group behind Sea Change, the first marine spatial plan attempted in New Zealand to safeguard the Hauraki Gulf. The aim was to provide a strategic, integrated and forward-looking plan considering the interests of all users of the gulf. While the intention was to minimise conflicts and maximise synergies across sectors little has happened since the group’s report was presented two years ago.

While it was always intended to be non-statutory, information was to be used to modify unitary, district, regional and coastal plans, including land use plans in catchments draining into the gulf. It was expected that the water quality work and its recommendations would feed into the Hauraki and Coromandel catchment plans that will follow the Healthy Rivers Waiora Plan Change 1 process currently undertaken by the Waikato Regional Council.

“Council people on the ground are pragmatic and get on with farmers,” he says.

“The big question mark is fencing of streams which won’t hit dairy farmers as hard as drystock farmers.”

There’s also uncertainty about capping of nitrogen inputs and maybe phosphate.

“No one solution fits all.

“And a lot of people aren’t happy about grandparenting suggestions and land use change restrictions.”

The concern is that what is eventually decided for farmers in the Waikato and Waipa catchments will be pushed on to those in Hauraki and Coromandel, but those catchments are totally different with different problems and different solutions, he says.

“But we would be all right when it comes to fencing.”

They’re down to fencing off very small streams on their farm with seedlings ordered for autumn to continue riparian planting next winter.

They have already joined up native bush blocks and covenanted about 15ha. Pinus radiata forestry blocks are due for harvest and won’t be replanted, with manuka being re-established on the steeper slopes. An increasing number of beehives are being brought on to the farm every year between November and February to feed on them as an extra income stream.

Promoting Red Devons

Dirk and Kathy Sieling have changed policy with their Red Devon bulls in the wake of the Mycoplasma bovis outbreak.

They produced breeding bulls from their stud set up several years ago, promoting them as an easy-calving option for dairy farmers. The young bulls have successfully been used for the last three seasons for mating both dairy heifers and cows, with four-day-old crossbred calves selling very well. They have also been leasing out surplus bulls.

“But with Mycoplasma bovis we didn’t want leased bulls being returned to the farm.”

So now they are selling bulls produced by their 30 breeding cows at a younger age.

“It reduces our income as we’re not leasing them out as one-year-olds, but we wouldn’t want to take the risk.”

Instead they are concentrating on filling farmer demand for younger bulls which they can keep on their farms and use twice, as a yearling with their heifers and then the next year to tail off their herd.

Calves are all weighed at birth, most coming in between 32 and 37kg. Stud bulls are selected primarily for gestation length and birthweight EBV’s alongside weight gain. With breeding only from polled animals 90% of calves are polled.

As well as being easy-calving Red Devons are docile and good on tough hill country, cleaning up pastures while maintaining condition and finishing early.

“The breed has more purity so there’s more hybrid vigour in the crossbred animals.”

Dirk believes there’s been a problem in the past with dairy farmers only looking for cheap bulls, but now many are seeing the increased returns from using a better sire. And they are taking more care to buy from breeders who belong to a breed society, with Dirk being a committee member of the NZ Red Devon Cattle Breeding Association.