Leptospirosis is often seen as a dairy disease while those working in the sheep and beef industry often fail to appreciate the significant risk they can face writes North Canterbury vet Ben Allott.

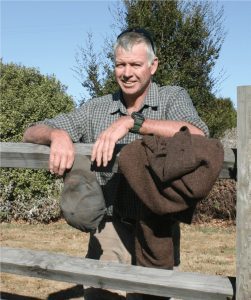

Andy and Cath Fox own ‘Foxdown’, a 1600-hectare property down the Scargill Valley that runs 6000 ewes and 200 breeding cows on land that has been in their family for more than 140 years. A farm manager works full time to run the farm alongside Andy.

Andy and Cath Fox own ‘Foxdown’, a 1600-hectare property down the Scargill Valley that runs 6000 ewes and 200 breeding cows on land that has been in their family for more than 140 years. A farm manager works full time to run the farm alongside Andy.

On January 7 this year, Andy was hospitalised with severe liver damage and dehydration, after experiencing crippling headaches for five-six days. He was diagnosed with Leptospirosis and remained in hospital for three days on intravenous fluids and antibiotics.

Others haven’t been so lucky, and Andy is aware of other North Canterbury farmers who have spent weeks in intensive care with the same disease.

The five days prior to visiting his doctor were spent on the couch dealing with a fever, sweats and chills, and some of the worst headaches he has experienced.

With headaches coming and going some days felt like he was on the mend to only have the headaches return with full force.

Cath insisted he go to the doctors when Andy described the headaches as “worse than the pain of losing my eye” in a fencing accident.

Andy, now 56, vividly remembers a Lincoln animal science lecture from when he was 21, where Alex Familton shared his experience with contracting leptospirosis. Even with this memory and experience on multiple industry boards where leptospirosis disease risk in agriculture has been discussed, Andy admits he failed to connect the dots when it came to his illness.

The delay in diagnosis and days spent on the couch could have been the difference between a minor illness or extremely severe disease, even death.

“I was aware of Lepto, but thought of it as a disease from cow’s urine that dairy farmers and meat-workers got. I hadn’t dealt with any cattle in December and Lepto didn’t even cross my mind.”

Two months later and Andy is still dealing with the impacts on his health and energy levels. Other farmers who have experienced infection share stories of recovery periods ranging from six months to in some cases several years.

Doctors have reinforced the key to a fast recovery is to not ‘over-do it’, and listen to your body and energy levels, difficult to manage when there are always jobs to do and a list of priorities that never gets any shorter.

Heavy fatigue still sets in during the day, and Andy is forced to bed most afternoons. In his case he feels lucky to have a farm manager to help run the farm through the illness but cautions many sole owner-operators would struggle to cope if they contracted Lepto.

Due to leptospirosis being a notifiable disease in New Zealand, his illness triggered a WorkSafe investigation that has opened his eyes to a number of risks onfarm. He was surprised, in particular, about the high incendence of leptospirosis in sheep. His primary concern is any risk to his family, and to the family of his farm manager.

Farming livestock delivers a sense of fulfilment and provides a lifestyle that ticks all the boxes for Andy and Cath, “we love being able to work in a business that has been in the family for 140 years and relish the opportunity to involve our family in this business, improving it for the next generation”.

“I don’t want to see anyone I love and care for go through what I have been through,” he says. The team at Foxdown are in the process of documenting the major risks of disease transmission, and identifying the practical steps to take to significantly reduce the threat of this disease.

Asked to share a single message to other farmers, Andy replied: “You think it won’t happen to you, and it probably won’t, but if it does you will know all about it.”