Simple and effective monitoring and management is reflected in Sam and Liz Barton’s award-winning two-tooth flock, Lynda Gray reports.

Body Condition Scoring, a take home tip from a Beef + LambNZ seminar in 2014 has been a cheap and game-changing management tool for Sam and Liz Barton.

“Since using Body Condition Scoring we’ve had a big lift in production by minimising the bottom end,” Sam says.

The Bartons, winners of the 2019 West Otago two-tooth competition, run their hands down the backs of all two-tooths and ewes at weaning in January, and then again just prior to spreading out for lambing. This year for the first time the rising two-tooths got the same BCS treatment in early February. The low BCS sheep were then shorn and preferentially fed.

The 30-second BCS check plus the pick-up of any obvious production-limiting faults at weaning is the starting point for pre-mating feed management. Any ewe at a BCS of 3 or below is drafted off, identified and then fed ab-lib through to mating when they join the B Flock. Typically they’ll end up the heavy weights – about 80kg – when they go to the ram.

‘We prefer to spend time shifting hot wires rather than starting a tractor to feed out balage.’

Some would say the feeding focus eight weeks out from mating is too much and too soon, but Sam has a different view.

“We would rather feed well year-round. It takes a lot of monitoring, fertiliser and feed budgeting but we know it’s worthwhile, and using body condition scoring we can allocate the right feed to the right ewe, at the right time.”

He’s calculated a maximum daily liveweight gain of 200 grams for a ewe on pasture covers of about 2500kg/drymatter/ha, so he likes to give plenty of time for the lightest ewes to put on weight.

“If we can have the ewes at a BCS average of 4 when they go to the ram we maximise conception, the ewes will winter with relative ease, and they have a comfort factor to come and go on.”

Judges described the Bartons’ winning two-tooths as a clean and even, true-to-type line bred, fed to handle the difficult hill country conditions. Their comments vindicate the management line taken by the Barton’s over the last three years which is all about feeding consistently year-round.

Feeding hinges on growing grass and pushing covers forward so that ewes have reserves on board to withstand the crunch periods typically in early spring and late autumn.

A shortage of feed has a huge effect not only on sheep performance but also finances because it could mean more time and money is spent on feeding out supplements, Sam says.

“We prefer to spend time shifting hot wires rather than starting a tractor to feed out balage.”

Ewes get an all grass diet from the lead up to lambing until late July of AR37 perennial-based pastures with cocksfoot, timothy and white clover.

“We spend a lot on soil testing, grass and fertiliser, as well as nitrogen in autumn so we can push the bowl of feed forward into winter.”

The annual fertiliser, and grass seed spend is around $111,000 ($23.47su), and on top of that is soil testing at about $1800. The big spend partly reflects the replacement of short-term rotation grasses with permanent varieties, but also the emphasis of maximising pasture cover for as long as possible.

Winter feeding of kale, swedes with supplements of balage, lasts for 115 days for hoggets, and five to six weeks for ewes. A one-year cropping rotation is followed: swedes then back to grass unless there is a particular weed or drainage issue that needs to be addressed.

Given the effort in growing grass, Sam is mindful of how it’s fed and in May and September prepares three feed budgets to cover the three altitude levels. A rising plate meter is used on the same paddocks each year and several readings taken to get an accurate average.

“I have also on occasions used cages to analyse pasture growth, especially when applying nitrogen, because I wanted to see what return I was getting for the money spent.”

The largely all-grass system is dependent on the rapid finishing of lambs to a target weight rather than price.

“Some people say you should target price, not weight and there is an element of truth to this. However, if the schedule is $80 for an 18.5kg lamb we hope our tight and conservative budget will take up the slack. Yes, it will affect that year’s profit but taking lambs to 20kgs in our climate may affect two years of performance.”

They target a 17.5kg carcaseweight for the first draft at weaning, and between 18 to 18.5kg CW throughout the season.

“This is the sweet spot for us because we get a respectable lamb cheque without compromising performance the following year, and it also minimises our workload through winter.”

Surplus ewe lambs are sold at the end of January to a repeat buyer who pays the going store price plus $15/kg.

“It’s simple and easy although this year because the store price was high we pulled the price back a bit.”

In the genes

Sam believes successful sheep production is 80% feeding. But he also keeps a close eye on breeding and genetics, taking care to select the right rams.

He selects first on type looking for spring in the rib and heavy bone, a medium type wool and clean head and ears. Those that make the first cut also have to be in the top 20% of SIL data for maternal traits, growth and survivability.

The Bartons have an ‘A’ and ‘B’ ewe flock. The ‘B’ flock is mated to a Sufftex and comprise ewes five-years-plus and those with a BCS of 3 or less. Ewes that are again drafted off the following year due to BCS are culled.

The breeding goal is for a consistent and uniform flock of moderately framed ewes that can hold weight through stress periods. They are pleased with overall flock performance but are always looking at ways to bump up production. One area they want to improve on is the 18% wastage between scanning and weaning. Most of the losses happen during lambing which Sam attributes to the fallout of lower BCS ewes. He hopes the problem will be solved with a lower stocking rate in the lead up to lambing, and a Flexidene shot at pre-lamb shearing to guarantee iodine.

Over the next five years there will be a move away from drenching to minimise the risk of resistance.

“Production might take a hit, but long term I think it will be successful.”

No ewes are drenched and the lambs are on a 28-day programme through the summer. The worm burden is monitored with faecal egg counts, and any issue addressed if required.

Farming pathway

Sam and Liz are equity partners with Jenny and Phil McGimpsey in Montana Pastoral Limited, and own 20% of the land, building, stock and plant. It’s a mutually satisfying and well-structured arrangement where performance and planning is discussed at three meetings, including an AGM, with an independent chairman Hamish Bielski.

“It’s a great team and we’ve had a lot of support and guidance from Jenny, Phil and Hamish,” Sam says.

The equity partnership formed in 2015 was the big leap forward the Bartons had been desperately seeking after following up to various degrees about 25 potential farming pathway leads.

Neither Sam nor Liz are from farming families but both had a huge liking for farming and the outdoors. Liz had a rural upbringing at Heddon Bush, near Winton, and from an early age had a hankering to go farming which she pursued on leaving school. Sam was raised in Wanganui. His father was a rural-based vet which helped stir Sam’s interest in farming, also, his uncles farmed at Mangamahu and he spent a lot of his spare time helping them.

After leaving school he did a stint in Australia working as a presser in a shearing gang, and on returning home ended up in the South Island on Harry Brenssell’s West Otago farm.

“It was a great start for me as it allowed me to gain knowledge and experience on an intensive and extensive commercial operation as well as a sheep stud.”

He worked there from 2000 until 2004, and returned in a senior role from 2009 until 2011 after five years at Peters Genetics, Beaumont.

Sam met Liz in 2010, they got married and in 2011 moved to Awatere Station at Waikaia owned by James and Denise Anderson.

Sam has high praise for the Andersons’ encouragement and what initially seemed like overly high expectations. James told Sam to set his sights high, look at the biggest and best farm manager job position, and use that to determine his biggest weaknesses and ways to build knowledge to overcome the weakness. For Sam financial and people management credentials were a limiting factor that he bolstered through an Ag ITO Financial and Business Management course. He also completed in 2015 Rabobank’s Farm Managers Programme.

The Andersons also provided the practical means to build equity. The Bartons bought Awatere cows and for five years calved them and sold the finished progeny. They were share-farming 140 cattle on two farms for three years and put the money they got from selling them towards the equity partnership. Throughout the equity building process and share farming they became familiar with Cash Manager, GST registrations and returns which made the transition to ownership a lot less daunting, Sam says.

Finger on the pulse

Body condition scoring, soil testing, and pasture measuring are simple practical tools the Bartons use to keep production on track. Cash Manager, another widely available tool, is used a lot for budgeting and planning.

“We use it to set budgets and keep tabs on expenses throughout the year. After setting the budget we will revise it often. Cash Managers ability to report is also very important because it keeps shareholders and our accountant up to date on financial performance”.

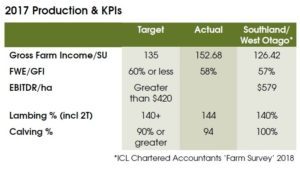

They run a tight budget so they can suck up any adverse price fluctuations and extreme weather events.

“When we get to late autumn we have a good handle on financial performance and that’s when we might look at capital purchases and larger R&M projects.”

Farm facts

Sam and Liz Barton, Wilden, West Otago

4500 (8.9 su/ha) sheep and cattle breeding/finishing on 553ha (510ha effective) rolling hill country ranging from 458-736 masl

Sheep (Romdale)

‘A’ flock – 1650 MA ewes

‘B’ flock – 670 MA and 5yr+ ewes.

810 two-tooths

850 ewe lamb replacements

Cattle (Angus-cross)

110 breeding cows

Key points

- Consistent feeding year round

- Using tools including Cash Manager, feed budgets and market indicators to monitor physical and financial performance and make timely decisions.

- Body Condition Scoring two times a year

- Feed budgeting two times a year with rising plate meter

- A supportive and well-structured equity partnership.