Sheep and beef farmers Steve and Cheryl Hirschberg have three children, three farms and they still find time to participate in the Coast to Coast and Ironman competitions.

Pinning Steve Hirschberg down for a yarn is no easy feat. Even once inside his house, he insists on standing in the kitchen while chatting, as he makes lunch during this brief break in his day. His phone rings constantly as he organises stock trucks, fertiliser spreaders, and shepherds, but eventually enough information on his farming operation is extracted.

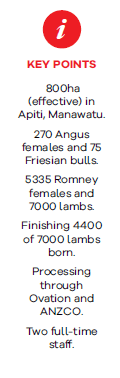

Steve and wife Cheryl run 800ha (effective) just east of Apiti in Manawatu. The original home block was his grandfather’s – bought in 1927. In 1996 Steve left his role as rural manager for the National Bank to move back to the home farm with Cheryl, and over the years they’ve sold and bought various different farm blocks nearby.

The system is a mix of family trust and partnership – comprising three relatively equal-sized blocks that range from 400m up to 600m above sea level.

The system is a mix of family trust and partnership – comprising three relatively equal-sized blocks that range from 400m up to 600m above sea level.

“Countless people have helped us to get where we are today,” Steve says.

Over the years Steve and Cheryl have been through some tough times with farming.

Steve says especially through 2008, 09, 10 and 11 with droughts and low stock prices.

Cheryl originally trained as a medical sonographer and it was her innovation to diversify into the sheep scanning business that got them through, enabling them to keep building on their landholding dreams.

“For 23 years Cheryl was beaten up in the winters but she got us through those tough years.

Cheryl was scanning up to 120,000 ewes a season, until one evening four years ago she came home from a long day in the yards and decided enough was enough. Her attention to detail (through her medical training) made her one of the best scanners in the country, but it was time to hand her clients over to industry colleagues and take a break.

Steve and Cheryl’s most recent land, bought in June 2021, was what they refer to as “Kate’s block”, after stock manager Kate White who lives in the house there. The block is 325ha and boasts 80ha of flats, bringing the total flat land count to 200ha across the three blocks.

The overall farm is classed by Beef + Lamb NZ in their economic services farm survey as Class 4, medium hill country and Steve agrees that this is an accurate representation.

The extra flats made the new block appealing for finishing country.

Steve oversees the entire operation, with Kate at his side managing the stock on a day-to-day basis.

“I’d be completely lost without Kate!”

The farm runs 30% cattle and 70% sheep, with the straight Angus herd used solely to clean up pastures for the sheep.

The cattle have to pay their way but they need them for the sheep programme.

Cattle are a valuable tool

There are 150 mixed age Angus cows, as well as 40 R2 heifers and 80 yearling heifers. All the maternal cows and replacement heifers are kept on the home block, the first and second calving heifers are kept on the higher terrace block and the B cow mob are farmed on the new block – Kate’s block.

All the yearling heifers are mated to low birthweight Angus bulls, which Steve says is essential to his farming system.

“Breeding cows are unprofitable enough as it is without not getting a calf out of them.”

Steve once read that if you don’t mate them until they’re a three-year-old they deposit too much fat around their mammary glands and it affects their future milking performance. Whether this is true or not is almost beside the point for Steve as there’s another benefit – calving yearling heifers gives him a gauge on temperament earlier, so females can be culled before being carried through to three years old.

“If I’ve got a wild cattle beast, I’ve only got myself to blame.”

The Angus bulls have been sourced from Ngaputahi, Stokman and Komako Angus in recent years, after having problems with structural breakdowns in the past. Since shifting breeders they’ve not had any issues.

Steve has developed a great relationship with Forbes and Angus Cameron at Ngaputahi, where he also buys his Romney rams, and enjoys the interest they take in ensuring everything is going smoothly with the bulls throughout the year.

Usually he’s looking for the best two-year-old bulls he can afford – moderate mature cow weight EBVs with above average 600 day weight figures and good ease of calving. He will try to buy the curve benders to suit the heifers and get that good growth.

Steve says because they’re killing rising two-year-olds, the 600 day weight is important. He doesn’t buy specifically for intramuscular fat, but knows it’s on the Ngaputahi and Stokman radars, so is going to get it anyway.

“Our profitability comes down to every cow having a live calf.”

The bulls are put out on December 10, with 45 heifer replacements part of the 250 females that go to the bull in total. Everything is scanned in April and anything that’s dry is culled. The remaining 50-odd heifers not put to the bull are finished and killed at 18 months of age.

As previously mentioned, the cows are a working tool to clear up the pastures, so Steve only carries as many cows as he needs to achieve this goal. For him, lambs are more profitable than beef progeny.

The bull calves are steered and killed over summer at 26–28 months old, to an average carcase weight (CW) of 330kg.

Steve doesn’t like the feed it takes to get steers through the second winter but has to if he wants 330kg CW.

All steers and the surplus heifers go into the ANZCO natural beef programme, who keep their premiums confidential. The criteria to enter the programme is that stock must be antibiotic free, grass fed and the farm must be quality assured. There’s no marbling criteria.

Steve was disappointed that ANZCO couldn’t take his post-Christmas cattle, and these had to be offloaded elsewhere at short notice.

“It’s bloody hard to farm like that.”

This lack of reliability in the beef processing system has meant he’s now considering leaving some of the bull calves entire and killing them at 18 months of age as bull beef instead.

In total there are 120 heifers and steers killed annually and all the supply contracts are left in the hands of Steve’s stock agent.

While very little technology is used within the cattle system, Steve has considered AI to reduce the bull buying costs, which is about $6000/bull. However, after doing the research, he realised the need for bulls wouldn’t decrease much, due to the demand on them during the second cycle with fixed time AI.

“AI conception would have to be up about 80% or more to reduce my follow-up bull needs.”

As well as the cow herd, Steve also runs a dairy bull programme. He buys 70 weaner calves a year from the Feilding sale yards, but once Kate’s block has been through more re-grassing, he will look to run up to 200 Friesian bulls.

They’re on a straight grass programme and they’re killed at 18 months of age. In fact there are no crops for any of the cattle at all.

“I hate mud.”

The mention of mud stops Steve talking as he reflects on the damage and hardships of those farming on the East Coast after Cyclone Gabrielle.

Lamb for dinner

There are 4200 mixed-age Romney ewes and 1135 ewe hoggets on the farm and Steve’s thought process is all about live lambs on the ground and finishing as many as possible himself.

“The lambs are our main source of income.”

Only 1800 of the ewes go to maternal Ngaputahi Romney rams, with all the two-tooths getting a Poll Dorset and 1400 B mob ewes getting a Landcorp Texel or Focus Prime ram.

“With my sheep genetics I always try to buy the best I can,” Steve says.

The weather at lambing time can be a mixed bag of freezing cold easterlies and snow showers so there’s no early lambs, even though the climate at Kate’s block is a couple of weeks ahead of the top block.

“Early lambing is too much pressure, so we focus on live lambs on the ground.”

Lambing dates reflect the change in climate over the three blocks, with rams going out on April 3 on Kate’s block, then a week later on the home block and April 17 for the high block. There is a two-week gap in the growth curve.

The scanning results are the proof in the genetic pudding for the sheep programme, with 209% in the mixed-age ewes and 195% in the two-tooths. The hoggets are mated also, and while they only docked 90%, they’re still carried through if they don’t have a lamb.

High-octane feed is grown for the lambs. In 2022/23 that was 26ha of chicory and 12ha of rape/plantain mix. Steve finished 4400 lambs of the 7000 born last year, with another 1100 kept as replacements. The remaining 1500 were sold as store stock through Ovation, with Steve avoiding sale yards whenever possible.

“It’s all direct to farm.”

Not everything can be finished and Steve says the male Romney lambs are the hardest to get away. These are sold store at 34kg liveweight from January to March. They want to have their ewes in acceptable condition going into the autumn.

In early March 2023, Steve only had 1600 lambs left on the farm and although the yielding was back on grass-finished lamb this season, Steve is pleased with how his lambs have performed.

“The lambs on chicory are smokin’.”

The lambs killed pre-Christmas off mum are 18.5kg CW and then after weaning on Christmas eve, the next 2000 lambs go out in January at 19.5kg CW.

“Christmas and New Year couldn’t come at a worse time for our farming system.”

The top block isn’t weaned until January but that doesn’t stop Steve getting every lamb on the farm away by June.

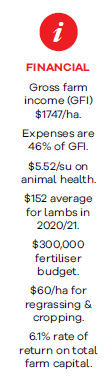

The total lamb production per hectare over the 2020/21 season was 142kg, well above the Beef + Lamb NZ survey’s class average of 99kg/ha. In the 2021/22 season Steve averaged $152 for every lamb on the place, although this will be back $30 this season.

Woeful wool

Shearing is a cost that Steve and Cheryl would rather not think about, with it costing them far more than it reaps every year.

“We’re paying $5.50 a sheep, which is right up there.”

The wool is almost worthless, as every strong wool farmer is well aware, but Steve is determined that he will continue his six-month shearing policy. It’s all about lamb survival for him.

Steve quotes considerable research that’s been done to suggest that there’s up to half a kilo advantage in lamb birthweight from winter shearing your ewes. The shearing needs to be done during the window of 70–85 days gestation. And that extra half kilo is all about lamb survival.

“Massey have proven the metabolic changes affecting the placenta, which pumps more into the lamb.”

Steve and Cheryl have been using the same shearing contractor for 20 years but their two sons, Bryce and Darren, are capable shearers so they chip in and help where they can.

Steve and Bryce shore all the rams this year, although Steve reckons Bryce well and truly stitched him up.

“He had a nice pen of Romneys and my pen had all the Poll Dorsets.”

Their daughter Sara also has an interest in farming, living near Dannevirke with her husband and three children.

Animal health

As analysed by Beef + Lamb NZ, the animal health costs sit at $5.52/su. The cattle get oral drenching, once as a weaner and then again six weeks later. Then again in the spring, and the following spring as well, if they’ve gone through a second winter. No cows are drenched after two years old unless Steve sees a light three-year-old after weaning.

A pour-on is used for lice and as well as BVD jabs in all the females (two for the heifers), copper bullets are given to the weaners and also the cows before they’re set-stocked with the ewes in mid-August.

“The bullet means that I don’t have to give them a jab pre-mating.”

The lambs are drenched two weeks before weaning and then again in mid-January before shearing. Some went six weeks without a drench this season.

Steve does faecal egg counts regularly to try to reduce the amount of drenching being done. The maternal ewes aren’t drenched at all, but the B ewe mob gets capsuled to slow the worm burden in the pasture contamination on Kate’s block.

He says it was all sheep prior to them taking it on, so it has high contamination.

Growing grass

Steve likes to ensure that the basics are done right in his farming system, and that includes fertiliser.

“I haven’t missed a year of putting 20 units of P on the hills in 27 years.”

Soil testing is undertaken biannually, with Olsen P levels of 13–14 on the hills and an acidity that sits at about pH5.8.

He says the fertiliser bill last year was $240,000 and they’ve budgeted $300,000 for 2023.

The normal policy includes putting PhaSedN or sulphate of ammonia in the spring. In the autumn it’s DAP and elemental sulphur, so it doesn’t get washed away in the winter. The hill country gets 20 units of P, 30 units of S, and then N twice a year, and the flats get 30 units of P but don’t have a huge requirement for S because it’s all ash flats.

In the 2020/21 year Steve spent $2.37/ha on fertiliser, well above the class average of $1.37/ha.

This is partly due to so much of it having to be flown on by plane.

“I only get the truck over about 200ha.”

Lime is also put on, with the home and top blocks getting one tonne/ha and Kate’s block getting two tonne/ha.

“We’re slowly working our way around the new farm.”

Cropping and re-grassing costs are high – $60/ha for the 2020/21 season, but this was due to a lot of re-grassing and direct drilling that was done on Kate’s block when they first took over. This was a necessary spend to get the grass and crops growing for the lamb finishing programme.

The total meat yield of the farming system is 235.5kg/ha over sheep and cattle, a figure that Steve and Cheryl should be pretty pleased with. But it’s the gross farm income that hits the mark – $1747/ha or $188/su, and with total expenditure at only 46% of the gross farm income.

“It’s the rate of return that I’m more interested in,” Steve said.

That rate of return on the total farm capital is 6.1%, taken from the Beef + Lamb NZ economic service’s farm survey of 2020/21.

The future

When Steve and Cheryl were asked about the future of the farming operation, he was quick to answer.

“Retirement.”

He says he’s got three kids and three farms so there’s space for everyone in the years ahead. But for now he and Cheryl are focused on ensuring they make time for themselves and keep the place ticking over.

Off-farm interests are a big part of life for the pair, who regularly participate in adventure racing. They race in the Coast to Coast together as a team, as well as Ironman events and other gruelling tasks that aren’t for the faint hearted.

“Sunday is our training day which means we get a day off the farm.”

Cheryl also works at the Broadway Radiology in Palmerston North as a sonographer two days a week. The commute is 50 minutes each way, made even longer thanks to the flooding during Cyclone Gabrielle taking out a bridge on the usual route.

Volunteer firefighting in Apiti is also on the agenda and thankfully their pagers didn’t go off during the visit.

“That’s our community service.”

The fact Steve and Cheryl are willing to volunteer time they don’t have is testament to the kind of people they are. Steve operates at a hundred miles an hour but he’s getting the results on the farm to prove that all the hard work is paying off. He probably runs in his sleep.