Low cost bull beef system fits well

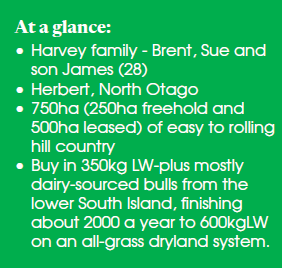

When the dairy boom moved in on their inland Oamaru farms, the Harveys took a break before settling on the Herbert farm to concentrate on bulls. Story and photos by Lynda Gray.

When the dairy boom moved in on their inland Oamaru farms, the Harveys took a break before settling on the Herbert farm to concentrate on bulls. Story and photos by Lynda Gray.

Big bulls and all grass are the long and short of the Harvey family’s beef finishing story.

Over the last seven years Brent Harvey, along with his son James and wife Sue have developed an effective low cost dairy bull-based finishing system to fit the growth, soils and terrain of their North Otago dryland farm.

There are no grazing cells, winter crops and huge spending on supplements. Instead dryland grass is grown in a holistic-type system, and up to 2000 bulls bought and finished to a target liveweight of 600kg as part of a July to pre-Christmas or January to June finishing cycle.

The Harveys buy in mostly Friesian bulls from the lower half of the South Island, self-sourcing from saleyards and onfarm, and from a network of livestock agents.

The main intake is during autumn of about 600-700 R2s averaging 380-400kgLW which are mostly finished before Christmas. From late July through to September there’s another intake of about 400 bulls, mostly R3 dairy bulls in the 450kgLW-plus range which are finished by January. More bulls are bought outside these times, according to seasonal conditions.

“We’re always on the lookout for bulls that meet our weight criteria,” James says.

The bulls graze diverse pastures of red, white and Persian clovers; plantain, chicory, grazing brome, rape, turnips and Italian ryegrasses.

The important thing with feeding, is that the bulls are not restricted, Brent says.

“We’re not out to max out grass growth, for us it’s more important that the bulls reach their full growth potential.”

The Harveys don’t get overly hung up on measuring drymatter and grass growth rates. However, they keep a close eye on how pastures should be shaping up at key times such as the end of August when they ideally want 1300kg DM/ha covers across the farm which is the ideal base to maximise spring pasture growth.

Another crunch time is from late December when they manage grazing to open the pastures up to encourage the growth of clover and plantain.

About 700-800 bulls in the 400-500kgLW range are wintered on saved grass and 400 bales of bought-in balage that’s fed from mid-August until spring growth starts.

By mid-September, during peak grass production, about 1200 bulls are in 25 mobs achieving average daily growth of about 2 to 3kg a day. That slows to about 1.5-2kg over the summer.

The first draft leaves about October 20. How quickly and in what number the rest follow depends on seasonal conditions and the availability of killing space. This season about 80 a week were dispatched from the start of November, leaving 300 onfarm by mid-December.

Sue keeps track of inward and outward-bound cattle. She records NAIT tags and truck arrival/departure details using Xero and Figured. It’s always a work in progress and every week is different. On the week Country-Wide visited, 84 cattle were dispatched in three loads on different days by different transport companies. Over the same time 150 cattle arrived in six loads over four days.

Past, present and future

The Harveys moved to Herbert seven years. The move followed 25 years of mixed cropping and bull beef finishing on two partly irrigated properties at Tokarahi in the Waiareka valley, inland from Oamaru.

Brent and Sue came to a crossroads situation where they realised that the future, given ongoing irrigation development in their immediate area, was in dairying. But it wasn’t a path they wanted to go down.

“It didn’t make sense to us, it would mean selling a farm, more debt and me becoming a dairy farmer which I didn’t want to be doing at the age of 50,” Brent says.

Instead they sold both farms – within six weeks – leaving them set up to start a new farming chapter. But finding a farm took three years during which they lived on the outskirts of Oamaru while Brent took on contracting work.

They bought the Herbert block in 2014 and Brent combined bull and steer finishing with contracting. But when neighbours Barry and Steph McMillan mentioned the leasing of their neighbouring farm the Harveys decided the time was right to grow the bull-beef business.

James was in on the discussions about taking on the lease block but went back to the United Kingdom where he was working on farms. However he returned permanently in July 2016 on getting the message from his parents that if he was serious about farming, he needed to come home.

After five years they’re still learning and refining the bull system. A difficult and traumatic time was Mycoplasma Bovis which struck in January 2019. It hit them hard, and they don’t want to talk about it, suffice to say it changed their finishing focus.

“We got caught out with light animals and a dropping autumn schedule… It cost us a lot and the lesson we learnt is that it’s better to concentrate on older and bigger animals because of their meat value potential,” Brent says.

M-Bovis aside, they’re pleased with what they’ve achieved.

“We’ve got the management sorted from June to Christmas, it’s the January to June period that’s difficult to nail because of the unpredictable weather patterns,” James says.

The Harveys’ system wouldn’t suit everyone given the feeding and juggling of multiple mobs in a summer dry-prone dryland system, as well as the almost daily handling, shifting, loading and unloading of big bulls. Also, adds Brent, a bull farm is never a pretty farm because there’s always a fence to fix or post to replace thanks to the testosterone-charged antics of bulls.

Typical bullish paddock behaviour is not always the case, James says, who has observed occasional random acts of kindness. A recent example was the mob of bulls who strip-grazed a paddock apart from a small area in the middle which on inspection revealed a nesting Pukeko.

Brent says they’re smart and that’s part of the attraction of farming them.

He’s always liked working with bulls and especially likes that they’re capable of piling on lots of beef.

Margin traders

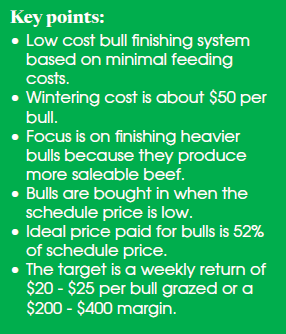

Brent and James describe themselves simply as ‘margin traders’, which is true but understates their speculative buying and selling approach underpinned by an encyclopaedic knowledge of past, present and projected beef schedules; typical weather patterns; and bull growth rates.

They buy counter-intuitively, avoiding grass market-fueled prices waiting instead until the schedule price dips. What they pay for bulls is based on the estimated saleable meat yield, which is 52% of schedule price.

The Harveys target a $200-$400 margin, or a weekly return of $20-$25 per head grazed.

Brent’s always been a fan of recording the weights of cattle and sheep. He started out with a Donald weigh box about 30 years ago.

“We thought it was great at the time.”

As technology has moved on so has he, buying more powerful and advanced weighing systems with add-ons.

Smart scales and set-up

Two years ago the Harveys upgraded to a Te Pari30 integrated yard, crush and scales. They knew exactly what they were getting because they tested a prototype of the system for Te Pari. The Harveys were ideal test candidates weighing up to 300 bulls a week and only a 20-minute drive from the company’s head office in Oamaru.

The Harveys weigh all bulls off the truck and graze them in arrival mobs of 40 to 50. They follow a five-paddock, five-to-seven-day rotation and are weighed six weekly but more regularly as they approach target weight.

In addition to weight, the basic details of breed, Nait tag number and bull vendor’s name are recorded. Target kill weights can be entered from which the number of days to slaughter is calculated based on past average growth rates. This information helps the Harveys forecast their kill plan as well as the booking of processing space and sourcing of new bulls.

The regular recording has helped single out and get rid of poor growth rate bulls sooner rather than later. It’s also helped identify health issues before they become a serious problem, a good recent example was a bull with Woody Tongue that Brent noticed because its growth rate was well below the mob average leading to closer inspection.

An add-on extra, a Te Pari dosing gun has reduced the spending on drench by more than $1300 a year. The gun is connected to the scales and calculates and dispenses drench according to the actual weight of each bull, rather than the mob average weight.

Bulls are quarantine drenched on arrival and again in spring after the first draft is sent away.

“We find that’s when we get the worm pressure, so we like to be proactive.”

They have a ‘spot drench’ policy treating those bulls in the bottom 10%.