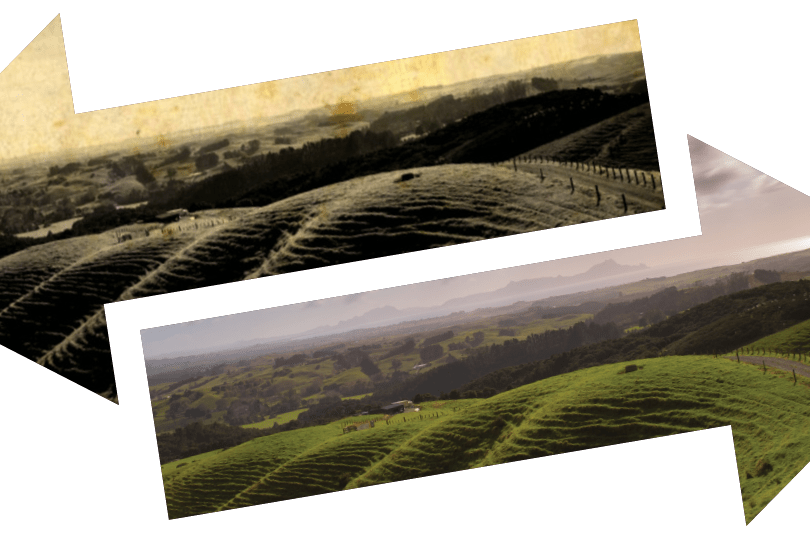

Looking back, to look forward

Kerry Dwyer reflects on a 40-year-old review of pasture management and animal production.

Kerry Dwyer reflects on a 40-year-old review of pasture management and animal production.

In doing some research for another article I came across a presentation that Dr Ray Brougham made to the New Zealand Grasslands Association in 1981. Forty years later it is well worth summarising some of what he said at that time because it is still pertinent in the 21st century.

Brougham was one of the leading NZ grasslands scientists of his day, working for the DSIR for much of his career.

Brougham cited much of what he had seen in his life and work since the early 1930s in this address, some of which is unknown history to today’s farmers. The computer chip was only getting started in 1981; the personal computer and cellphone didn’t exist.

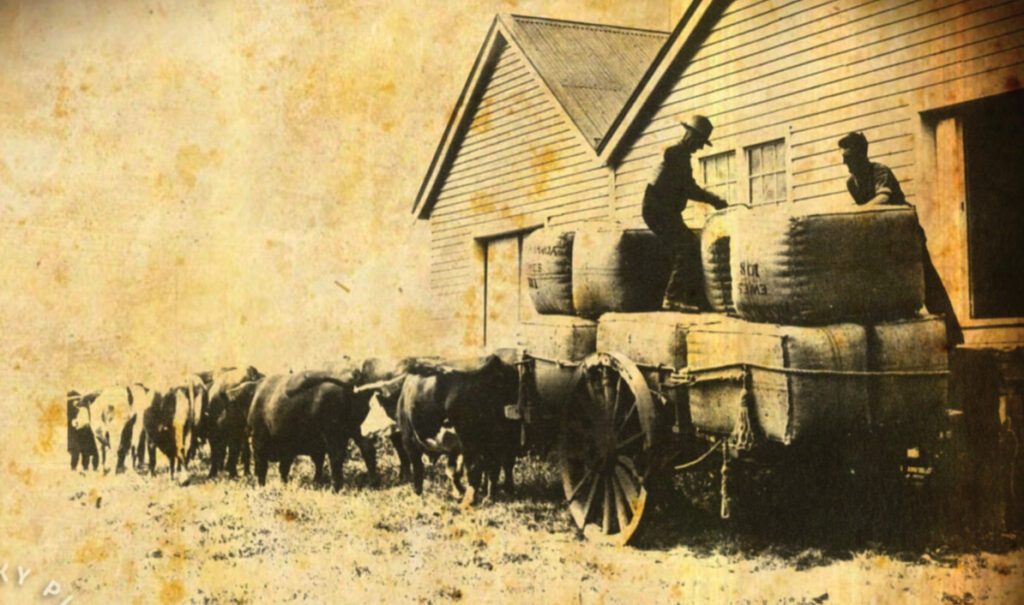

Pastoral farming in 1930

In his address Pasture Management and Animal Production” presented in 1981 he first looked at what NZ pastoral farming looked like around 1930.

In the early 1930s the average dairy farm milked 23 cows, producing 160kg MS/cow/year. There were 72,000 dairy farmers who milked about 1.67m cows.

There were no income taxes.

The average sheep per farm was 1027, average fleece weights about 3.5kg. About 8% of all stock were lost annually and lambing percentages averaged about 85%. The national flock was 17.5m breeding ewes.

In 1930 there were about 4000 tractors used in farming.

About 500,000ha was in field crops, with wheat and barley yielding between 2-2.5t/ha of grain and ryegrass seed yielding under 500kg/ha.

In 1930, 450,000t of superphosphate was applied to about 950,000ha of pasturelands. Total sown grassland was about 7.5m ha.

Work was being started on the use of copper and cobalt to cure bush sickness.

Some significant developments from 1930 to 1981

Cultivar development and seed certification was begun to improve pasture plants. White clover was proven to be of value in soil fertility build-up.

It appears that rotational grazing was first put into practice in NZ in 1928 on a Manawatu farm and in 1931 the use of rotational grazing showed an increase in milk production from 320kg MS/ha to 440kg MS/ha. It was found that rotational grazing usually became important only at high stocking rates. (Stocking rates at the time were considerably lower than in 2022)

Other major developments in animal management were: artificial breeding; non-stripping of the dairy herd; the use of penicillin and other drugs; planned and synchronised mating.

In the late 1940s and early 1950s there was considerable concern at our abilities to compete with synthetic fibres and margarine.

In 1954 Dr C.P. McMeekan stated in the NZ Dairy Exporter that the NZ farmer had three major efficiency cards to play:

- a) the untapped potential in the application of existing knowledge;

- b) the inter-changeability of the major types of animal production;

- c) the untapped potential in the application of future knowledge.

The scene in 1981

The average dairy farm was milking 123 cows on 80ha, producing 270kg MS/cow/year. There were 17,000 dairy farmers milking about 2 million cows.

The average sheep flock was 2,750 ewes producing 5.25kg of wool and almost 100% lambing. The national flock was just under 50 million breeding ewes.

The future from 1981

The scope for increased animal production over the next 50 years is very high.

(Ray Brougham then looked at various factors that would allow this prediction to be true)

Improved cultivars and new species: It is only at the highest production levels that improved pasture cultivars are being shown to be of value in increasing production. The genetic potential of improved plants can only be expressed when management enables this to occur.

Some very significant increases in meat production per hectare are shown, attributable to the use of improved clovers.

Pasture Management: In our farming systems, the leaves and green parts of pastures trap and use up to 4% of incoming visible light in the photosynthesis process. In nature some associations of organisms or plants trap up to twice as much.

There is plenty of scope to devise systems that will utilise higher proportions of incoming sun’s energy.

Nutritive value: Much improvement has been made to the quality of feed eaten by animals throughout the year, and there is scope to improve further.

Utilisation: We do not utilise a high proportion of feed grown each year on the average farm, we will need to develop systems of management that obtain increased utilisation of feed grown.

Plant nutrition and soil fertility: Some 1970s research showed that the grazing animal is not really an aid in soil fertility build-up as previously thought, rather it has a strong influence on the leaching and volatilisation of nutrients through concentrating these in dung and urine.

One can envisage the day when the level of fertiliser usage will be more closely linked to the level of production desired.

Pasture pests: The removal of chlorinated hydrocarbons (e.g. DDT) cost NZ agricultural production. The future control of pasture pests and diseases will be by the integration of different methods and approaches to control.

Irrigation: In all regions, water limits growth during some period of the year. Yet NZ has only a relatively small area under irrigation, and in systems of irrigation that some consider extremely wasteful of water.

Plant Breeding: The development of plants with better photosynthetic capacities, and more efficient water and nutrient use, higher and more regular nitrogen fixing capacities, increased nutritive value and better tolerance to pests will occur through the efforts of geneticists and plant breeders.

Animals: Does the future see completely automated milking parlours a reality?

In the next 50 years production levels will probably be at least twice present (1980) levels, and possibly much more. The average dairy farmer (of 1980) is producing at about the level of the top farmer in the 1930s, so there is plenty of opportunity for further development. All that is necessary will be some independent and creative thinking, some hard work, and the right incentives.”

Today there are about 11,000 dairy farms in NZ, averaging 155 hectares per farm with 445 cows per herd, producing about 390kg milksolids (MS)/cow/year. There are about 4.9 million dairy cows.

In 90 years that is 85% fewer dairy farms, milking 19 times more cows per herd, producing 240% more per cow, with 290% more total cows.

In 2021 there were 23,000 sheep and beef farms in NZ, averaging maybe 2000 sheep per farm on 650ha average. Fleece weights were about 5kg per sheep and lambing 133%. The national flock is 16.5m breeding ewes.

In 90 years that is maybe half the number of sheep farms, producing 40% more wool and 48% more lambs per ewe, with 5% less breeding ewes.

Finding how many tractors there are today is difficult, and do we count the ones sitting under the trees?

In 2021 there was about 150,000ha of field crops, with wheat averaging close to 10 tonnes/ha of grain and barley 7.5t/ha. Ryegrass seed yields average about 2.5t/ha.

In 90 years that is about 70% less arable area, with yields increasing 300-400%.

Total sown grassland is about 7.4m ha, similar to 1930. Fertiliser applied is equivalent to 1.7m tonnes of superphosphate and 980,000t of urea.

In 1930 we were a country of cattle farmers (72,000 dairy farmers included), then sheep increased in numbers and declined again.

We again seem to be a nation of cattle farmers.

- If you are interested in more detail, Brougham’s works have been reviewed by Warwick Harris in Revista PASTOS, 1993.