Intensification secures future

Coming home to help out his parents on the family farm, has seen Tim Dangen convert a small-scale beef operation to a substantial calf-rearing operation. By Glenys Christian.

Coming home to help out his parents on the family farm, has seen Tim Dangen convert a small-scale beef operation to a substantial calf-rearing operation. By Glenys Christian.

Lincoln graduate Tim Dangen made huge strides in his 18 months on a Southland dairy farm.

As his three-month placement extended out he was rapidly promoted from his farm assistant role.

“In two months I was 2IC then in another two months I was farm manager,” he says.

But by Christmas 2014 he had reached a crossroads. Farm owners Simon and Janine Hopcroft wanted him to contract milk their 1000-cow herd, while his parents, farming near Muriwai, northwest of Auckland were keen to move the farm to the next level. The Hopcrofts had been very generous to him and ran a well-oiled operation, he says.

“It was a case of choosing life in Southland or coming back here with family, friends and my future wife Jenny.”

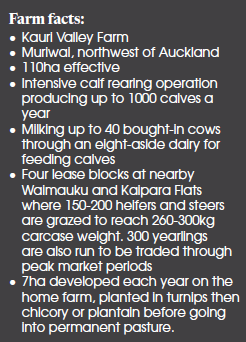

So he returned to the 110-hectare (effective) farm his grandparents bought with his parents in the 1980s. And over the last seven years along with his parents he’s overseen its conversion from a small scale beef operation to intensive calf rearing, which turns out up to 1000 head annually.

When his grandparents, Selwyn and Una, first arrived from Kaitaia to take advantage of better educational opportunities for their children closer to Auckland they farmed a small block at nearby Waimauku. Their son, Lyall, Tim’s father, persuaded them to buy the much larger farm at Muriwai but there were no boundary fences, house or water supply.

“There was another 100ha of bush on the farm which had the ability to be grazed,” Tim said.

They built up to running 500 Perendale ewes and about 100 Angus or Hereford breeding cows as they tackled development work. But with little income both Lyall and his wife Robyn worked full-time off the farm.

Lyall set up a firewood business, then ran a sawmilling operation in Swanson, west Auckland, for 20 years while Robyn returned to nursing after the birth of their five children. Along the way they also fenced off a 30ha stand of bush including large kauri in the middle of the farm as well as waterways.

Then a sudden brain tumour diagnosis saw Lyall unable to work for five years until surgery was performed.

‘It was hard on him and the farm,” Tim says.

“We kids were too young to run the farm but we got through. Mum and Dad showed inspiring resilience through this period which has rubbed off on all of us kids.”

As the only boy he was never really pushed into farming and intended after finishing his Bachelor of Commerce with agriculture with a double major in rural valuation to head down the rural professional path.

“But Simon and Janine were inspirational people,” he says.

“They had a vision of what a farm can be if the balance is right between environmental, social and financial goals and I saw how much joy that can bring.”

Arriving back home he found the farm was “at a teetering point”. On the plus side there was low debt and his father didn’t employ anyone to help him out.

“But Mum and Dad had identified that something needed to change and I’ll always be thankful to them for that,” he said.

There had been five years of “unintended neglect” through his father’s illness then it took the next five years to get the farm to the state it had formerly been in.

“All three of those goals were not where we wanted them to be but we had the opportunity to turn it around,” he says.

“We needed to establish a business model so we could afford to stay here.”

Making the change

Knowing the answer was to intensify they opted for calf-rearing, arriving here through using what advantages the farm and location gave them. Being close to many lifestyle blocks they hoped to command a premium for their calves. They thought there was an opportunity to provide a flexible service to smaller farms as well as concentrating on cutting costs.

The 40 beef cattle with calves at foot were sold and his father started work on building an eight-aside herringbone dairy. Tim helped him finish it in 2015 and they were underway for their first season.

Thirteen cows were bought along with 187 four-day-old calves from the Tuakau Saleyards, south of Auckland. The calves’ arrival on the farm is staggered over an eight-month period to maximise grass cover both on the home farm as well on four lease blocks they gradually took on at Waimauku and Kaipara Hills, further north.

With a bank loan needed to fund development work which also included building calf-rearing sheds cashflow was paramount.

“We knew quickly that calf-rearing was profitable and our aim was to get enough profit to cover the rest of the business.”

The Dangens took on the remainder of the development work required themselves.

They subdivided seven large paddocks to make 40 smaller ones, put in a new water supply system and embarked on fertiliser and pasture renewal plans.

“We knew it was a large workload but we’re both good at prioritising and we went for the low-hanging fruit,” Tim says.

While they ran at a loss for the first two years not covering overheads, now margins of about $900/ha have allowed them to take on a full-time worker on the home farm and a part-time stockman on the lease blocks.

Stock numbers have built up to about 40 cows being milked, some coming from Waipu, in lower Northland as no replacements are kept. High milk production is a must so up to 15 Holstein Friesians which are F12 and above, are bought in every year. They’re not worried about somatic cell counts, and as the cows don’t need to walk far to and from the dairy udder formation and feet aren’t so important so that reduces the cost.

Their spring-born four-day-old calves are still bought at Tuakau which saw them reduce numbers by around 100 head last year due to its closure during the Auckland Covid-19 lockdown. But up to 400 of their autumn-born calves come from one farm at Waipu.

“They’re very good calves and we’re lucky to get them.”

They will spend four weeks in the calf-rearing sheds being fed four litres of whole milk from the cows once a day from day one. That’s supplemented by some milkpowder mix fed ad lib but feeding mainly whole milk means they avoid animal health issues such as scours, Tim says.

“Coccidiosis is the biggest problem so we give all the calves a drench at four weeks then go into the usual drenching programme from 10 to 12 weeks.”

From 300 to 400 spring-born calves mainly go to lifestyle block owners, who take them in single or double numbers when they weigh 100kg. Some are sold privately and some through stock agents.

While their autumn-born weaners are sold off the home farm yearlings all go to the lease blocks with the Dangens having a fluid stocking system depending on grass availability.

“That means we can hit the markets if the prices are good,” Tim says.

“There are a lot of synergies because we can sell when there’s a lot of grass and prices are high but are still able to utilise our grass with the weaners coming through.”

They also make around 200 bales of baleage annually. The lease blocks are consistently stocked with 150 to 200 heifers and steers which will go off at around two years of age for the heifers and steers at 30 months.

Heifers will usually reach 260kg carcaseweight and steers 300kg before they leave. Also run on the lease blocks are 300 yearlings which are traded through peak market periods.

Boosting the average weight

They are still breaking in some of their scrubby land covered in gorse and tobacco weed at a rate of about 7ha a year. After it’s cleared and cultivated a winter crop of turnips followed by a summer crop of chicory or plantain will be planted then after a dressing of nitrogen it will go into permanent pasture. Weaners take the first graze in autumn then the milking cows will be moved on to it.

The Dangens did grow a larger area of summer crop including chicory, plantain and red clover but have now moved away from that.

“We wanted to match the feed demand but found it more economical to largely destock before the Christmas to March period,” he said.

“There were too many variables as we can have up to 400 millimetres of rain over December, January and February or none. Chicory’s a marvelous plant but it’s not foolproof – it needs a freshen-up.”

This year in early February there had been no rain since December 15.

Their pH levels have been boosted from 5.3 to 5.9 in some areas with the application of five tonnes/ha of lime. About 500-600kg of straight superphosphate goes on with Olsen P levels which were about seven now up to the mid 20s.

Now the farm is facing another crossroads with Tim’s youngest sister, Kaycey, in her last year at Massey High School. So plans are well underway to build a wedding venue on the farm and rent it out along with their six-bedroom farmhouse.

“Long term we won’t stay as a large calf rearing unit,” Tim says.

So by the end of this year they aim to be running the wedding venue themselves as part of a transition plan which will gradually see its income grow as “the wedding season extends into the calf-rearing season”.

A balanced city and farm life

Tim Dangen enjoys an enviable work/life balance. When he finishes work for the day on his parents’ Muriwai farm he drives 35 kilometres to Hobsonville Point, one of Auckland newest suburbs, acclaimed for its future-thinking design.

He and wife Jenny, who married at the end of last year, decided it made sense for them to live halfway between their respective jobs, as she’s a tax accountant working in the north Auckland suburb of Albany.

“We enjoy the balance of city and farm life and leaving every day makes me more motivated,” Tim says.

“We can go and watch the All Blacks and then drive home. I wouldn’t trade it.”

While he used to play rugby he now opts for summer touch and an occasional game of squash. For the third time last year he placed second in the regional finals of the Young Farmer of the Year Competition, but at 29 consoles himself he can have two more goes.

“I’m quite competitive and quite well-rounded,” he says.

“I enjoy stacking up against other young farmers.”

And this year he will get the chance to do that at the Grand Final in Whangarei on July 7, having just taken out the Northern Region title.

Despite the farm being only a 40-minute drive from the Auckland CBD in good traffic he says there are surprisingly few issues that come with being that close to a large population mass. A number of lifestyle blocks are by the top entrance to the farm but otherwise it enjoys privacy. And the proximity comes in handy when they advertise their calves on Trade Me as they command a premium because they’re so close at hand for many buyers.

There’s also a responsibility in being close to the city which sees them regularly engage with the local Waimauku School, always supporting its ag day, as well as Mt Albert Grammar. Plans are to use their planned wedding venue to host more school visits which Tim hopes may help correct the “harrowing statistics” of just 160 graduates a year completing agricultural and horticultural degrees while around 3000 opt for environmental studies.

“We need more doers rather than finger-pointers,” he says.

“We talk about the challenges facing our industry but the solution is attracting young people because they will solve them.”

He doesn’t see so much of a rural/urban divide but says agriculture is still fighting the old stigmas of too much work and not enough pay, which is slowly changing.

“The responsibility is with all farmers to be advocates and champions of the industry,” he says.

He believes that has been corrected over the last few years as with Covid-19 more people have had cause to reflect on who the economy’s essential workers actually are.

“The country needs to look at what we’re good at and all the support roles in agriculture need to be promoted,” he says.

“Everything taught in high school needs to be taught through the lens of food production. It starts with people already in the sector.”