In pursuit of excellence

Dave Buick doesn’t do participation. His attention to every little detail is evident from the high-performing farm to his rise to the very top of shearing sports in New Zealand, and his remarkable recovery from a horrific onfarm accident that almost killed him.

Rebecca Greaves reports.

When it comes to the numbers, Pongaroa farmer Dave Buick and his calculator are closely acquainted. He is constantly fine-tuning, running scenarios on where money is to be made, and he’s not afraid to try something new – if he thinks it might improve his system.

Dave and Rebecca Buick, along with baby Michael, first graced the front cover of Country-Wide magazine almost 20 years ago, on their way to first farm ownership. It was meant to be a stepping stone, before they moved somewhere closer to town. The Buicks still own that farm, and they’re still in Pongaroa.

The couple are a team, and their enthusiasm for the agriculture sector and the pursuit of excellence is uplifting. At a time when farming can seem a daily battle, Dave’s genuine enjoyment from being on his farm is a tonic.

Dave subscribes to the saying that behind every great man is an even better woman. He might be the hands-on grunt, but he’s quick to give full credit to Rebecca, who he describes as the glue that holds everything together.

“The most important thing is having a good wife. Behind every good man is an equal wife.”

Son Michael is now 20 and a fourth Buick family member was added after Country-Wide visited, Gemma, now 15.

There are many moving parts to the Buicks’ business, which includes the shearing contracting business Shear Exhaustion, which employs up to 20 people in peak times and has more than 200,000 sheep on the books. Rebecca also works four days a week at the local school, as well as doing the books and wages for the shearing business.

Dave is the first to admit he is competitive, and it’s that drive to succeed that took him to the top of the competitive shearing scene in NZ. In 2021 he was at his peak, winning both the North Island and South Island Shearer of the Year, among other titles. The only big one to elude him is the one everyone dreams of, the Golden Shears Open title.

But October 20, 2021 was the day everything changed.

While undertaking onfarm drainage a newly dug ditch collapsed on Dave, burying him up to his chin under tonnes of sodden dirt.

He was airlifted to hospital with an eye-watering list of injuries, not least being that his pelvis was mashed – there was basically nothing holding the top of his body to the bottom. All his internal organs had shifted 4cm.Hard to believe, but Dave says the accident was a blessing, as it made him take a hard look at what was most important in life. Shearing all day, working all night was not sustainable.

“You can pile as much money and time into a farm as you like and it will just take the whole lot. Rebecca used to say – you’ll burn out, I want to retire with you. It’s how we got to where we have got to, but it became the norm.

“I’m a doer. When I was in hospital the psychiatrist came round and she said David, here’s my card, you’re going to need it. You’re what I call an active relaxer.”

For an active relaxer, the idea of spending two months lying flat on your back, dead still, sounds like a nightmare. But in typical Dave style, he maintained a positive attitude throughout the whole ordeal.

“I knew that a second earlier I was bent over and I would have been dead. That was my motivation.”

Rebecca says his mental health was good throughout, if he had gone to a dark place, it would have made things much tougher.

On leaving hospital, Dave was transferred to a retirement home, which he loved. He made Rebecca bring weights so he could work on his upper body strength.

“I loved the oldies; I had a ball. They used to wheel me outside on nice days and I’d joke that I was the bouncer. You make it what it is. When I got there, they asked me if I wanted the door to my room shut, no way, I wanted to wave to people and talk to people.”

He was pencilled in to enter rehab until February. Dave had other ideas; he was determined he was going home for Christmas.

The mental toughness that had taken him to the top in shearing came into play. “In any sport you have to be fit, but to go that next step it’s all about the top two inches. I was doing workouts every night with shearing; I was used to it. I had the motivation, I just needed them to give me the tools to move my body.”

As long as he wasn’t doing damage, he pushed the envelope to speed up his recovery.

At one point, the orthopaedic specialist offered to sign Dave off, if he never returned to work. Rebecca says that was the only time he got angry. “He said you can’t just write me off, I’m not going to accept that. He could have accepted that and sat on the couch for the rest of his life.”

Not only has Dave returned to work, he’s picked up a handpiece and he’s even shorn in competition again, in a father/son event with Michael. Nerve damage to his right leg means it’s numb, and he can’t feel his foot. But outwardly, watching him shift bulls on the farm, you would never know.

“Rebecca is really the rock of the family. If she’d been in hospital, then we would really have been in trouble. These goals, for me to represent New Zealand (in shearing), it’s quite selfish. The whole family has to support you. It wasn’t just my goal; it became the whole family’s goal. The staff and crew had to pick up the slack if I was away.”

The fact he was able to run the shearing crew from his hospital bed, and everything still happened, shows what amazing staff he has, he says.

Michael was near the end of his final year at school, and was able to come home to run the farm, with oversight from local farmer Shaun Baxter. “I think Michael was just mature enough to handle the pressure. He had one broken-in dog and I was trying to give him the whistles for three other dogs from my hospital bed in Wellington.”

He hasn’t lost his competitive spirit, but Dave has gained a new appreciation for what he has, and has learned to relax and enjoy life a little more.

“You think, how can any good come of it? But to appreciate the cool things we are doing here and be proud of it, to be proud of our kids. I could have continued working that hard, and what for? I’d always said I wanted to take the kids snorkelling in Fiji and to be honest, it would probably never have happened. We went and at one stage we were snorkelling along, with all these fish and I turned around and there was Gemma, doing cartwheels. It was the best.”

Later this year Dave and Rebecca are off to Bali, just the two of them. It was a profound realisation that they have done the hard yards, many of them, and it’s time for a bit more work/life balance.

“I still love being out there on the farm, but live a little. I used to drop sheep at the neighbours and they’d ask if I wanted a cuppa, I’d always be too busy to stop. Now, I have the cup of tea. I wasn’t here for six months and everything ticked away. A farm will take everything you have to give it.”

Trading up

Taraora was the original first farm of 205 hectares, bought in 2001. The couple had looked at leasing but reasoned if they scraped under their fingernails, they were better off getting a foot in the door with ownership.

“Rebecca had shares in a house in Wellington and we were pretty frugal so if we went to a more isolated area, we could get in. This was always meant to be a stepping stone but it’s such a great community and return on investment is good out here because land is cheap, or cheaper.”

Eight years ago, they bought 400ha Pine Hills, at the top of the Puketoi Range. The idea was to lease it out for five years while Dave gave the competition shearing a serious nudge, then farm it as the breeding unit, using Taraora for finishing. Enter the march of the pine trees.

“The farm was surrounded by pines; we were the last farm left. As a business decision, we sold Pine Hills to pine trees in order to buy Te Rau three years ago.”

Since moving to Te Rau, they have embarked on an extensive development programme, 6km of fencing, fencing off waterways, a central laneway, hundreds of loads of rotten rock, drainage and re-grassing. They borrowed money up front to fast track the development, but the majority is funded from cash flow. The final project in the face of strong headwinds for farming is a new set of cattle yards. Dave is building them himself, of course.

High-performance stock

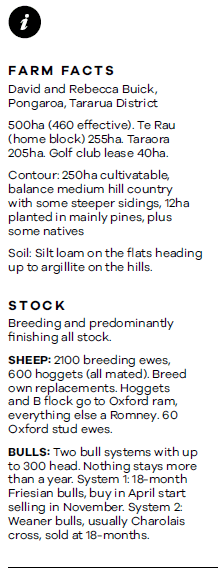

The Buicks are breeding and finishing all progeny, unless the store market goes crazy. Dave is constantly evaluating where the best dollar is to be made, so policies are flexible, depending on the season.

They ditched cows in favour of bulls about four years ago, and that’s where the biggest bang for buck is, as well as building greater flexibility into their system.

They finish about 300 bulls annually, split roughly half and half into two systems.

The first is 18-month Friesian bulls, bought about April and carried through the winter. They start heading out the gate in November, which suits their pasture growth curve. The bulls are killed as the farm usually starts to dry out, allowing lambs or replacement ewe lambs to come down on to the flats.

The second system comprises weaner beef bulls, usually Charolais cross and purchased from weaner fairs or sourced locally. These are gone by 18-months – nothing stays more than a year, or one winter.

Through spring the weaner bulls average 2.2kg-3kg/day in the cells, and the two-year-old Friesians are doing 3kg, Dave says.

The bulls are in one-hectare cells and shifted every two days. Mob sizes vary from 25 to 33, depending on the age of the cattle.

Everything is killed and for the last two years bulls have averaged 335kg carcaseweight, but the end result can vary. “The big Friesians, we can take them up to 700kg liveweight. It depends on the schedule and grass covers, but it gives us options.”

At $2000-$2500/ha gross margin, the bulls are hard to beat, Dave says, but you can’t have bulls everywhere.

Complementing the bulls is a high-performing ewe flock. Scanning this year was 202%, up 10% on last year, with 22% triplets. Dave views this as a potential one third of his lamb crop, and triplet ewes are nurtured. “It’s there, what do I have to do to capitalise on it? If I muck it up, that’s a huge loss,” he says.

Triplet ewes are identified and drafted at scanning. These ewes are prioritised and put on high-quality feed.

The bull unit is sown in a mix of chicory, red and white clover and Italian ryegrass.

“This year the priority triplets, the older girls and B flock have lambed on it, and they are looking mean. I will get most of those lambs, as triplets, killed off mum.”

All hoggets are mated, with a target weight of 43kg by May 1 to go to the ram, and this year scanned at 110%.

Hoggets and B flock ewes go to an Oxford ram, while everything else goes to a Turanganui Romney.

Earlies (B flock) have a ram date of March 20, while mixed age and two-tooths at Te Rau are March 27. Down the road at Taraora mixed age and two-tooths go to the ram on April 4.

Dave double lambs on some country. He’s just docked his earlies and put them out on the hills, swapping with the hoggets, who come down to lamb on the easier country.

On the cropping side, they plant 20ha of oats and rape. The rape is used in autumn for the lambs before being locked up for the bulls. The bulls are break-fed with twice-daily shifts through winter and are on the rape for eight to nine weeks.

It then goes into chicory and red and white clover, becoming the summer crop.

“That lets the clover get established and the following autumn, six months later, I direct-drill a tetraploid like a fast-growing Italian. You get a really clover-dominant pasture for the next four years.”

This system gives him the option to put in-lamb ewes through the bull unit prior to set stocking.

Know your numbers

Dave loves doing gross margins. He spends hours running the numbers and he is on Farm Focus every day.

Dave loves doing gross margins. He spends hours running the numbers and he is on Farm Focus every day.

“It’s constantly learning and adjusting, but I’m always evaluating and doing the gross margins to see if it’s on. You always have to be playing around with the calculator. We have a lot of moving parts and I’m very in touch with our business. I know exactly what’s coming in and going out.

“We’ve got a photo of Gemma sitting on the toilet when she was about three, with a calculator – I was so proud.”

The focus is spending money in the places that deliver the greatest return – drainage, fencing and new grass.

Despite the intensive development programme, total working farm expenses are 56% of gross farm income. This is largely down to the fact they do almost all of the work themselves, including fencing and cropping. Dave even services his own quads and tractor. He can weld and obviously, he’s fairly useful with a handpiece.

Gross farm income has averaged just shy of $1500/ha for the last two years, though with the current climate and high interest rates, Dave expects this year to be tighter. The last two years they have averaged $156/lamb, but again, Dave says those days have gone. It’s hard to know where the bottom will be – he’s revised his budget down more than once.

As well as Farm Focus, they use Cloud Farmer as a notebook to store all information and data and, spoken like a true farmer and shearing contractor, Dave is constantly checking the weather. His favoured weather app is Windy.

“We do have quite intense systems, that’s where you make the money, that fine tuning. It’s in me to go hard, and I enjoy going hard but now I say every day is a holiday – I do really enjoy farming. “I do a lot of hours to get the results. No one is perfect and we make mistakes, just like the next person. The tough times we have been through are what has given us the knowledge and tools to get through the next challenge.”

Oxford stud

An exciting diversification is the addition of 60 Oxford stud ewes.

The first crop of lambs is on the ground, and Dave can’t wait to weigh them.

He’s a fan of the breed, using Oxfords as his terminal sire for about 10 years now. “I drove past this guy’s ram paddock one day and they were big boned with a muscly back end – just what I wanted.”

The rams, which belonged to Barry and Malcom Scott, were Oxfords. When Barry passed away, Malcolm approached Dave about taking on the stud. The timing wasn’t great, as Dave was in hospital after his accident and they decided to pass on the opportunity.

After trying a few other breeds, with limited success, he picked up the phone and fortuitously, Malcolm still had the stud ewes.

“They had really good genetics and I ended up buying 60 ewes. I purchased a good sire ram, he did 400grams/day from birth to February, so it’s some really cool genes to start my stud off with.

“The oldest lambs are four weeks old and they’re thumpers, I can’t wait to get them across the scales. The Oxford is basically a black-face terminal that grows like snot and still has a bit of wool at lambing time.”

There’s already been plenty of interest in the rams and, with Dave’s love of figures, it’s a great fit.

“I’m already doing a lambing beat twice a day so it’s really only tagging lambs that’s extra work. We’ve set the stud up properly and we’re keen to grow it.”

Saving lives

Dave Buick is trialling a Vitamin D injection in his quest to banish the bearing.

Research has shown a link between ewe bearings and Vitamin D deficiency. Having heard about it, he decided to trial the injection this year. Though he says it’s too early to say conclusively if it’s been a success, it’s looking promising.

Ewes are given the injection at scanning.

Dave’s own research into the cause of vaginal prolapse (bearings) came about after a flood in 2004.

“There was so much feed and we fed everything the whole way through. We got 10% bearings – I had to buy an extra dog tucker freezer.”

Based on what he discovered he adopted a new system that he has implemented every year since, with good success.

After their first cycle, ewes are fed maintenance only. They feed for three hours a day and are locked up for 21 hours in a holding paddock.

“This also builds up covers for winter and doesn’t skint the paddock out. You’re only hammering one or two sacrifice paddocks. That system has really dropped the bearings incredibly.”

Dave admits this is a labour-intensive process, but one he feels is worth it. They also sew up all bearings, having about a 75% success rate.

“It’s a huge cost, not just the animal and her lambs gone, but she’s not there next year or the year after. It’s the cost of replacing her, it’s an opportunity cost.

“We do a lambing beat twice a day and I say – I’m off to save lives.”

Handy on a handpiece

Father Christmas bought 14-year-old Dave a handpiece, the best investment he ever made.

He started out shearing his father’s sheep and never looked back. When they bought the farm, he and a group of mates would shear each other’s sheep, then other people started asking them to shear. Shear Exhaustion was born.

“That’s why the banks loaned us the money, they could see the off-farm income. Rebecca was working in Palmerston North every day, and they could see I could shear myself out of trouble. The deal was, whoever was home first had to cook tea.”

Dave’s first taste of competition shearing came when he was at Smedley and the cadets entered the Onga Onga Tikokino competition. He won the Junior.

“Dad was a judge so I was always taught to shear clean. It’s just a passion, a huge part of our life and always will be.”

Dave went on to win countless titles and represent New Zealand, reaching the number one Open shearing ranking for the 2020/21 season. He was recently given the honour of Master Shearer by Shearing Sports New Zealand.

To show just how competitive Dave really is, Rebecca says even in the chopper on the way to hospital he asked her if he would be able to go to the Paralympics.

Dave reckons he’s pretty much retired, though he might chuck his handpiece in as he follows Michael and Gemma around the competition scene, more of a hobby.

“No, you won’t,” Rebecca chips in quickly. “He won’t go to participate; he doesn’t believe in participation. If you do it, you do it to win. Maybe his expectations won’t be as high, is what he means,” she says with a wry smile.