Ben Allott

Leptospirosis is a disease transmitted from animals to humans (a zoonosis), and from animal to animal. Leptospirosis is caused by bacteria known as leptospires that multiply in the kidneys of infected animals and are then shed in the urine. The bacteria thrive in moist or wet conditions and can survive in the environment for months under the right conditions.

Livestock become infected by grazing pasture or drinking water contaminated with infected animal urine. People working in close proximity to animals are at risk of infection through contact with urine splash, or contaminated water. Leptospires can cross through cuts or cracks in the skin or through the mucous membranes of the eyes, nose or mouth. It can be carried and shed by almost all warm-blooded mammals, including farm, domestic and feral animals.

Many sheep, beef and deer farmers I talk to are very surprised to find out that their animals are highly likely to have been exposed, and that many of the animals on their farms are likely to be shedding leptospires in their urine.

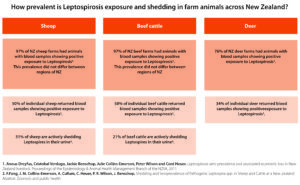

The table below highlights some alarming New Zealand data on the prevalence of leptospirosis exposure – 97% of sheep and beef farms have evidence of lepto exposure, and about 50% of individual animals (both sheep and cattle) have been exposed. This was consistent across all regions of NZ.

Among developed countries and those with temperate climates, NZ has one of the highest rates of human notified cases of leptospirosis per year. It is an occupational disease associated with livestock exposure with farmers and abattoir workers representing about 80% of notified cases each year (ESR 2002-2015).

In the 1970s, before widespread vaccination of dairy cattle, an average of 488 cases a year were notified (11 per 100,000 people). Recent data (2001-2014) shows an average of 2.24 cases/100,000 people (about 110 notified cases per year). Like many diseases it is thought that the notified cases are the tip of a much larger ice-berg.

In the first week after exposure, leptospires spread in the blood (septicaemia) and during this stage the common symptoms reported are; severe headaches, high fever, muscle pain, chills, painful abdomen, lethargy, and jaundice (yellow skin and eyes).

The severity of infection and organ systems affected are variable with the common organs systems affected being the liver, kidneys, lungs, and the vascular system. Infection can result in permanent complications, usually from severe kidney or liver damage.

Many farmers report being unable to work for months and in severe cases, may be unable to return to running their farm. Infection in pregnant women can result in miscarriage and disease in children can be particularly severe. In some mild cases, infection may just feel like a bad case of the flu, with headaches and fever.

In Country-Wide, April 2019, Andy Fox from North Canterbury shared his story of contracting Lepto and how this disease continues to affect him.

Exposure to Leptospirosis can be assessed by measuring the levels of Lepto antibodies in human blood samples. Recent NZ surveys have estimated that 10.9% of meat-workers, 6.6% of sheep, beef, and deer farmers, and 5.1% of veterinarians have significant antibody levels in their blood, indicating prior exposure to this disease.

When you stop to consider the risks of exposure to animal urine/urine contaminated water in our industry, there is a very long list. A short list of common exposures I came up with:

- Lambing ewes

- Calving cows

- Treating ewes with bearings

- Crutching lambs

- Handling dags

- Uddering ewes

- Pushing sheep on to crutching trailers or conveyors

- Mud splashing in yards

- Gutting and handling offal of home-kill/dog-tucker sheep, or hunted pigs and deer

- Clearing blocked drains in killing sheds, yards, footbaths

- Eating food with un-washed hands

- Smoking with un-washed hands

- Clearing rodent nests in sheds, animal feed etc.

Most of us, and I hold my own hand up here, do all these jobs and more, often with very little thought to personal protection. My hands always have a missing knuckle, or a cut down a finger. Every calving I do, or every bearing I put back in, brings with it the risk of infected urine splashing into those wounds. Nearly every time I am in a set of cattle yards I get splashed in mouth or eyes with mud, or collect a wet tail to the face. Our families, wives, and children are often exposed to significant risk as well.

Leptospirosis is a notifiable disease. As such, if you, a farm worker, or a contractor, contracts this disease, WorkSafe will be notified and there will be an investigation of your health and safety plan, the provision and use of personal protective equipment (PPE), awareness of the risks, and the steps you have taken to reduce the risk of this disease to people in your business.

How can farmers protect themselves?

Awareness – People in your business should be made aware of the risk of leptospirosis and they should be aware of the steps you expect them to take to reduce these risks. Leptospirosis and risk reduction steps should be documented in your farm health and safety plan.

PPE – A significant opportunity exists to reduce exposure to urine through wearing gloves for high-risk activities, and through wearing appropriate clothing. All calvings, lambings, and replaced bearings should be done while wearing appropriate gloves. Gloves are cheap and easy.

Hygiene – Wash hands thoroughly before eating, drinking or smoking. Dress and cover cuts and abrasions that are likely to get splashed or wet. Do not smoke or eat in yards.

Vaccination – Vaccination of livestock has been shown to be a very effective tool in reducing the rate of animal disease and in reducing the rate of animals shedding leptospires in their urine. There is no available vaccine to protect people from Leptospirosis but animals can be vaccinated to reduce the rate of disease, and reduce the shedding of leptospires in urine.

As a group, dairy farmers are aware of the risk of Leptospirosis and it is estimated that more than 90% of NZ dairy herds are annually vaccinated against this disease. This practice has significantly reduced the rates of human Leptospirosis in NZ dairy farmers. In contrast, vaccination rates in beef, deer, and sheep are far lower with observations that 18%-42% of beef, 5%-13% of deer and 0.6%-1% of sheep farms vaccinate against leptospirosis.

The WorkSafe website (https://worksafe.govt.nz/topic-and-industry/working-with-animals/prevention-and-control-of-leptospirosis/) has a well laid-out section with good information on this disease, it’s transmission, and information on protecting you, your family, and your staff. I highly recommend you take the time to have a look at this information, talk to your local vet, update your farm health and safety plan, and talk to your team about the new steps you need them to take while working with animals.

- Ben Allott is a North Canterbury veterinarian