Hooked on stud breeding

Max Tweedie was just 21 when he founded Hallmark Angus Stud and after buying the Waiterenui herd recently. He’s set to have one of the largest recorded Angus herds in the country. By Rebecca Greaves. Photos by John Cowpland.

Max Tweedie was just 21 when he founded Hallmark Angus Stud and after buying the Waiterenui herd recently. He’s set to have one of the largest recorded Angus herds in the country. By Rebecca Greaves. Photos by John Cowpland.

Max got his first stud cattle at the age of 18, and he was quickly hooked after selling a bull to a stud breeder for $22,000 when he was still a teenager.

In hindsight, Max, 28, says the result was a total fluke, but it whet his appetite for breeding cattle – and it paid for his OE.

Max’s passion for cattle oozes out of his pores and his enthusiasm is unbounded when talking about his favourite subject, fostered by a long family history of breeding (he is a fourth-generation breeder).

He counts himself lucky to have the opportunity to farm on his own account, alongside fiancee Lucy McLean, at a young age.

“I’m farming the farm I grew up on, it’s buzzy. We have been able to make our own mark on it, which is a cool feeling.”

Max got the bug for farming from an early age, but an interest in breeding took longer to develop, despite his grandfather, the late John Bayly, being a respected breeder. “As a kid we’d go there at Christmas and help him shift the bulls, but it didn’t mean much to me then.”

It was when he went along to Future Beef and took part in the hoof and hook competition his interest was piqued.

“I got totally hooked on the beef cattle side. Breaking in and presenting a steer, leading it through the ring and then getting into judging and stock skills.”

Through Future Beef and the Angus Association, Max travelled around the world, including the United States, the United Kingdom and Australia.

It’s been his goal to learn as much about beef cattle as he can.

“I’ve always been thirsty for knowledge and, if I’m interested in something, I tend to go full hog on it.”

At the age of 18 he got his first stud cattle after flushing a cow that belonged to his grandfather, breeding four calves.

“I absolutely fluked it.”

He was in his third year at Lincoln University and put them in the Gisborne Combined Angus sale where his grandfather had always sold his cattle.

‘‘I sold one to a breeder from Southland for $22,000 and I thought ‘oh, this is easy.”

It took him another 10 years to sell a bull to a stud.

Max says the experience taught him a lot, particularly the importance of investing in the right animal. The cow he flushed was magnificent; sound, with an excellent maternal background, genetic merit and she looked the part. Those principles have formed the basis of Max’s approach to breeding ever since.

“That day I said, ‘yea, this is me, this is what I want to do’.”

Given his family history, Angus was the obvious choice for Max. Maternally, Angus ticked all the boxes for him as the best allrounder.

Max’s ultimate goal is simple, he just wants to be a good farmer. To be a good commercial farmer and have good genetics, producing cattle people want, is the aim.

Genetics to the fore

The visual aspect of an animal is important to Max, but he’s also developed a keen interest in genetics.

After his OE he spent six months studying at the University of New England in Armidale, Australia, a place he describes as the mecca for animal breeding. He was fascinated by genetic evaluation and successfully applied for a job with Beef + Lamb Genetics.

The role initially involved measuring animals and turning the data into information for farmers, but he soon moved into an extension role and ran the national beef programme in genetics, including the progeny test that involved 2200 commercial beef cows across six properties using AI.

He was able to leverage some of the relationships he had formed in Australia to kick-start a Trans-Tasman maternal project.

While working for B+L Genetics he founded Hallmark Angus Stud, paying his father a market rate grazing fee to run the animals on their family farm.

Max knew it needed to be market rate, as that was an opportunity cost to his father, and also to be fair to his sisters.

It wasn’t a handout.

“The prover for dad and I was, although it’s high input and costs, we have been able to keep the stud profitable after the first year. To do it within a sheep system was key.”

After five years with B+L he returned home and worked for his dad for several years.

Max says this would have continued longer but, sadly, his mum was diagnosed with terminal cancer and the family completed farm succession early.

“Nine months later mum died. We were very lucky we had multiple blocks so now my sisters have a block, and Lucy and I have a block.

“Dad was always of the mindset that before you get tired and old you should have a crack, and he just backed us. We do have significant debt now but that’s the exciting part of farming. It’s very motivating.”

Ownership at a young age provides the opportunity to pay off debt, and to grow. Max is keen to grow his operation, the key driver being his dream of transitioning away from commercial cows and focusing on breeding bulls, because that’s what gets him out of bed in the morning.

And his dream is about to be realised with buying the Waiterenui herd from Will and Viv McFarlane.

Establishing the farm system

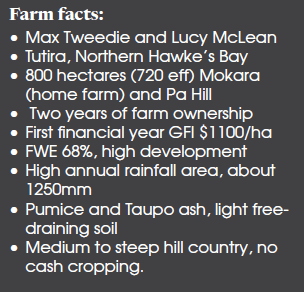

Max and Lucy have nearly completed their second full year of farm ownership. They have invested heavily in setting the farm up for an onfarm bull sale, as well as moving an old farmhouse on for them to live in. This enabled them to employ a staff member.

For these reasons, farm working expenses (FWE) were high in year one, at 68%. Max says they are tracking for 55% this year, which is still a touch high, but the reality of stud farming and the rising cost of inputs.

The high FWE are down to the extra labour and costs associated with stud breeding, and initial outlay to establish and improve facilities to enable an onfarm sale, including a purpose-built selling complex, as well as shifting the extra house on.

In their first financial year they recorded gross farm revenue of $1100/ha and an economic farm surplus of $300/ha. Max had hoped for a much better surplus result, but that came down to the higher FWE.

The stud may be his passion, but Max believes it is important to maintain a commercial side to his operation, and sheep underpin his entire business.

Max says the light, free-draining soils on the farm lend themselves well to cattle, though there is minimal area suitable for cultivation.

The pumice soil doesn’t respond well to harrowing and tillage, so they direct drill. Kale crops are used in winter for commercial cows and then put into new grass, which is used for finishing lambs and bulls. Max has found Mohaka hybrid ryegrass gives him good persistence and performance. When it runs out after three to four years, it goes back into kale.

The sheep system is simple, solely terminal, and Max says they couldn’t operate without sheep.

All 2100 ewes go to a Suftex ram on March 10 and their two-year lambing average is 163%, giving them about 3500 lambs, all of which are finished. They kill about 30% of lambs off mum, a number Max hopes to lift.

They buy his father’s five-year ewes (from a different farm) annually and, although they do have an older flock, this works well and they are able to get lambs away fairly quickly.

“I really love the sheep and enjoy that side of it. I get a kick out of fattening lambs. It’s fun and I also think it’s important to maintain our relevance there with clients.”

Sheep are set stocked in lambing country and, post lambing, are spread out through the calving country, a great tool to combat worm burden.

Cattle numbers are at 230 commercial cows and 170 stud cows, but as the Waiterenui herd comes on they will transition out of the commercial cattle.

“You could say we are a bit cattle-heavy. We do the weaner fair thing, I love that, there’s a bit of an art to it.”

He has put a Simmental bull to a B mob in the past, saying it keeps him honest and ensures they put the best cows to the best bulls, commercially. This year they topped the weaner fair at Stortford Lodge on price per kg and British bred price per head, with $3.90/kg for 256kg calves.

Opting for onfarm sales

Hallmark Angus was founded in 2015 and 2022 marks their seventh annual two-year-old bull sale. Forty-five bulls will be sold at their onfarm sale in the second week of June.

Last year was their first onfarm sale, with the first five sales held at Stortford Lodge saleyards. They hosted over 300 people for the 2021 sale, achieving a top price of $48,000 and an average of $9632.

Max’s approach to breeding is a combination of the visual appeal, how an animal moves and its soundness, and his time spent studying genetics and evaluation means he balances the presentation with an objective eye.

“It’s more of an art than a science. I think successful breeding programmes combine the soundness and functionality component with that science. They understand their clients’ needs and are driven to create a product that suits those needs.”

Max believes everything starts with the cow. He is focused on where the cow will be, with changing land use (particularly forestry and carbon) meaning cows are pushed further into marginal country. Given sheep are more profitable and the cow has to pave the way for other stock classes, it’s all about maternal performance.

He says tools to improve maternal performance are poor and the EBVs to describe the cow are not good enough and need improvement. To make any real progress on beef cow maternal performance, more description and information is need.

“My goal is to ensure the cow is functional, and weans a calf early every year for years on end.”

Max is less-focused on the carcase component at this stage.

He wants females that become excellent replacements and calves that have a downstream value for the people who finish them.

Max sees the cow of the future being an efficient, moderate-sized animal with a high value calf.

This is why his ears perked up at the opportunity to buy the Waiterenui herd, which he considers to be the pre-eminent maternal herd in the country.

Sale two-years of planning

Will McFarlane had indicated he was considering retirement and his children, although keen farmers, were not keen to continue the stud, which has a 108-year history. Max approached Will and, after two years of planning, they came to an agreement.

In early April 330 mixed age cows from the Waiterenui herd moved to Tutira. Will is set to continue as a mentor to Max, helping guide breeding decisions and working with clients.

Max says Will thrashed his cattle and there are few herds that have had that kind of environmental challenge, years of drought in a highly summer-dry hill country environment.

“The stock shift so well, we have had cows and bulls from there and they always come to the top.”

Max always admired that, and their maternal qualities.

They will have more to eat at their farm but will have to climb more for it.

“It’s going to be great, population genetics, big mobs, more pressure, more to choose from – the survival of the fittest idea has more relevance.

“ It’s a once-in-a-lifetime opportunity and I’m so lucky to buy those cows.”

He praised the McFarlane family and their contribution to the beef cattle industry.

Waiterenui has been the seed for so many of the herds today. Three generations of stud masters have all heavily influenced the industry. The influence of their sires has been enormous and the Waiterenui cows have always been a feature.

They want to make it long-term.

“Bull breeding is a 40-year game, if you do it right.”

Stock

- About 7500 stock units wintered

- 2100 Romney breeding ewes

- 230 commercial cows

- 170 stud cows

- Supporting stock