Joanna Grigg

We need legumes to thrive to overcome the weakest link in our pastoral systems – a lack of nitrogen (N).

The boom-bust of grass-dominant pastures can be broken by adding and managing legumes better, plant scientist Professor Derrick Moot of Lincoln University says.

A trial at Lincoln University (Mills et al. 2009) showed dryland pasture growth on low N soils struggled to crack six tonnes per hectare (T/ha) but, with nitrogen, grew close to 16t/ha. All at the same rainfall. When it comes to better plant yield, nitrogen (N) is the game-changer.

In New Zealand N fertiliser application quadrupled from 100,000t in the early 1990s to 400,000t in 2016 as farmers chased the grass response. But bag N applied ad lib is now considered out-dated and shown to undermine pasture quality. Over-doing bag N will reduce clover, in turn reducing stock performance as lactation and growth are linked to legumes. A thatch of dominant grass will build up which in turn, reduces N cycling in the soil.

Moot is an advocate for getting N into dryland systems using legumes that naturally fix N, rather than rely 100% on fertiliser.

“Legumes do not require additional N fertiliser, but (N fertiliser) can be used on the shoulders of production seasons to boost grass growth, provided the extra feed grown is eaten and not left to shade the legumes.”

Moot describes this legume-based grazing system as taking longer to see the benefits than the immediate fix provided by N fertiliser, but worth the wait.

“Once the whole system has been developed, the production rewards are tangible and locked in at a relatively low cost.”

“This is the lowest hanging fruit for much of our pastoral landscapes.”

Moot said that a legume N system is the most sustainable system he can demonstrate for meat and wool production for the environment, taking all issues into account.

As sheep and cattle progeny grow faster with legumes, their time on pasture and their corresponding methane footprint is reduced.

“This is the way our industry can continue to get more efficient.”

Hill clovers next

Professor Derrick Moot, of Lincoln University, describes direct grazing of lucerne by ewes and lambs as now “routine across many dryland farms”, despite the need for significant management changes for many farmers.

“You can find direct lucerne grazing platforms from Northern Southland to the Central Plateau; it’s been a slow but steady increase,” Moot says.

Just over 1000 farmers are signed up for the Lucerne eTexts from Beef + Lamb NZ. But the message about the benefits of using legumes, notably annual clovers in mixed swards on hill country, is still largely unheard. Moot says the potential for annual subterranean (sub) clover on north and west facing hills is hugely undervalued.

Seventeen years of work by the Dryland Pastures team at Lincoln University has focused on the science of introducing and managing legumes, to use whatever water as efficiently as possible, to grow the best yield and quality. The small team has been Professor Moot, Dick Lucas, Dr Annamaria Mills and Malcolm Smith, with help from post-graduate students.

They’ve proved their worthiness in the field, raising twin lambs at 300 grams/head/day prior to weaning on dryland legumes. Legumes were either lucerne and lucerne mixes, or subterranean clover (with or without balansa clover) mixed with ryegrass or cocksfoot. This core work at Ashley Dene has been reinforced by successes on commercial dryland farms that became case studies for the Dryland Pastures programme.

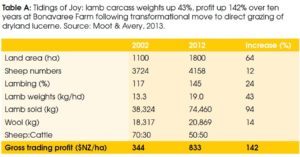

On the case study farm Bonavaree, Marlborough, (Table A) the move to direct grazing of lucerne and transformation in management increased lamb weights by 43% and gross trading profit by 149% over 10 years. This has been well documented by the Dryland Team and the Avery family have been proactive in sharing the message to other farmers.

The Dryland Pastures team also initiated and documented the sub clover experience at Tempello, Marlborough, intending to encourage its replication across other dryland areas. Sub clover was identified as the legume of choice at Tempello to provide the high-quality feed and N input the uncultivatable hill country required. Subdivision and stock water were put in place and a new grazing management system rolled out. As a result, the number of lambs sold prime at weaning (more than 32kg) has lifted from 50% to 89%.

Moot has noticed interest building in annual clovers among North Island farmers. Over an 18-month period he has made many visits to North Island farms to talk about clovers.

“Some Wairarapa farmers visited Tempello in Marlborough in 2014 and came back to become the nucleus of farms successfully using subterranean clover systems in the North Island.”

Dan and Reidun Nicholson, Tokaroa Farm, Wairarapa, were inspired by their visit south and went on to host a research project on whole-farm mapping to stratify clover management across land classified on the basis of aspect and slope. The findings were presented at the 2019 NZ Grasslands Association conference.

Moot is counting on a new Beef & Lamb NZ-funded programme Regenerating Hill Country Pastures, to help shout the message from the hill tops. The programme will have on-farm demonstrations as well as research on legumes (for low and higher rainfalls), identify growth curves of different legumes, quantify biophysical aspects, as well as use micro-climate and mapping information to help select the right legume.

Options include suckling, cluster and striates clover for high country, red and white clovers for all-year-round wetter climates, subterranean annual clovers for warmer dryland, and top-flowering annuals for forage crops or particular paddocks that may be either heavy soils, water-logged at times or in a good drilling site.

Moot would love to have funding to have more plant scientists on the ground to help with the move to legume-focused grazing management.

“Often a quick chat and reassurance is all that’s required to give farmers the confidence to go ahead and change their grazing management,” he says.

He describes the process as two-step; understanding the legume plant itself and a change in mentality to alter grazing in summer to knock back the long grass to help annual clovers have space to germinate and succeed.

“I’ve seen farmers have that light bulb moment when they see all the clover in their paddock.”

Moot said fertiliser and seed agents are important to drive the change too. He was meeting Ballance fertiliser reps that day, to ensure they feel comfortable with the message.

Pastures that don’t have a clover plant every two steps are considered low in legume, Moot says. Clover content should be increased through promoting of seeding from existing plants or over-sowing. Legumes consistently fix about 30kg N per tonne of above-ground legume grown and provide feed with an energy level of greater than 11 MJ/kg DM and crude protein above 24% for most of the year (Lucas et al., 2010).

The message to farmers keen to explore dryland legumes is to get on their knees and identify the legume species in existing pasture. These ‘persisters’ are likely to be the species to run with. The Dryland Pastures website is a good place to help identify species and cultivars, and design a plan to build both their number and yield.

Not bog standard

Speaking at the NZ Grasslands Association conference in October/November, Professor Derrick Moot told a tale of impressive performance at Bog Roy Station.

Speaking at the NZ Grasslands Association conference in October/November, Professor Derrick Moot told a tale of impressive performance at Bog Roy Station.

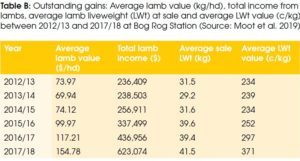

Now, with published animal performance data to back up the ‘talk’, the full extent of achievements on the 2860-hectare station can be seen from the implementation of a lucerne grazing system and better management of annual legumes on the hill.

Co-authored by Gundy and Lisa Anderson, Bog Roy, and Peter Anderson, Stockcare veterinarian consultant, Moot describes the report as a good news story all round.

Lamb income has gone from $230,000 to $620,000 and 10kg liveweight added to the average lamb weight at sale. Gundy Anderson said they published the results to inspire other farmers to use lucerne and find legumes that work for them.

“We took heart from Doug Avery’s story and have an open-door policy ourselves for people wanting to learn more about what we have done.

“I guess we also wanted to address the sceptics that thought the ewe flock production lift was simply from a reduction in cattle.”

The Upper Waitaki Merino property collects only 420mm of rainfall each year on average. This has been capitalised on by sowing deep-rooted lucerne plants that are never nitrogen (N) deficient, Moot said.

The Upper Waitaki Merino property collects only 420mm of rainfall each year on average. This has been capitalised on by sowing deep-rooted lucerne plants that are never nitrogen (N) deficient, Moot said.

“The plant can maximise the available soil water, particularly in spring, well ahead of any grass-based alternative.”

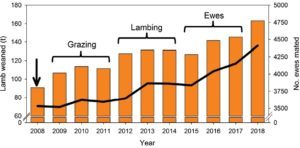

Stage one of the Bog Roy transformation, as described by Moot, was direct feeding Merino ewes and lambs on lucerne, rather than cutting it for hay. Production saw an immediate lift from 2008 to 2011, with an extra 20 tonnes of weaned lambs, despite little change in ewe numbers.

Each year, for seven years, the lucerne and ryecorn area was increased by 30ha. As the areas of lucerne grew, there was a need to set stock the lucerne for a short period during lambing, and new management skills were required. In this case, set stocking is carefully managed for a short period of time to avoid compromising the lucerne. By 2016, 50 tonnes more lamb meat was weaned than in 2008.

Direct lucerne grazing meant the ewes were better fed during lactation so lambs grew faster and were heavier at weaning for sale. What followed was a flow-on effect in the next three years, when more ewes were mated and at heavier weights. This was because there was more feed grown across the farm, particularly on the hills when the lucerne was being grazed, he said.

Flock performance and financial changes from 2012 onwards were documented using the flock recording programme StockCare. By 2018 the mixed-age Merino ewes achieved 141% lambing (to tailing), and pre-weaning lamb growth rates of over 270 grams/head/day which allowed weaning after 80 days. The lamb weaned per ewe mated has increased from 25 to 37kg over the decade despite increased feed demand from 900 more ewes. An existing small irrigation consent has been transferred to allow the development of a centre pivot irrigated block (lucerne/red clover) that can be used for finishing those weaned lambs.

The system has evolved over 10 years, with reduced supplementary feed made and fewer animals retained over winter. Ryecorn has become an integral part of the winter feed.

Gundy and Lisa have had to hone their skills at rotationally grazing large mobs of ewes and lambs on lucerne. This started once lambs were about three weeks of age and mobs were drifted off hills to start a six paddock lucerne rotation.

As the area of lucerne expanded across most of the easier contour area, they had to learn how to lamb on lucerne and start rotational grazing earlier.

Central to all changes has been the drive to understand the legume management required to drive animal production, Moot said. A copy of the NZ Grasslands Association Paper is available on-line, in the October 2019 edition of the Proceedings.

HILL LEGUMES STORY NEEDS TELLING

The story yet-to-be-told at Bog Roy is the Anderson’s success with improving the yield of annual clovers on their 1500 hectares of hill country.

David Anderson said while some plot trials were done on legume content following different grazing regimes, the funding stopped and the results are yet to be published.

The large-scale result of removing grass competition during summer and winter, then spelling clovers during spring, can be seen first-hand right now this spring, Anderson said.

“We found that the existing legumes such as suckling, striates and cluster clover increased leaf diameter and size, and with space to flourish, created a wonderful feed bank.”

Anderson said that visitors to the station have focused on the lucerne story and irrigation but not a lot of focus has been directed to the hill legumes, apart from the Merino Benchmarking Group when they visited.

“This is a shame as the hill legumes have really driven production for us; ewes lamb on it and birth weight has increased to over three kilograms, even for twins.

“Through changes in management the land keeps improving.”

Anderson said that the industry needs to focus on genetics as well as feed systems, as they go hand in hand.

“You can have a flash car but if you don’t have fuel or if you have shitty fuel going in, it won’t drive.”

Hill faces that have been subdivided down from 650 and 450ha blocks to 100 to 150ha blocks, which is a good size to use his 3200 ewes post-weaning to knock down grass cover. Mother nature can crisp and frost the grass, cattle can then clean it up, allowing legumes to flourish in spring, he said. Four kilometres of fencing has been done this spring to help with utilisation.

“We’ve noticed a real lift in lamb birthweight from ewes grazed here, with the small one- and three-quarter kilo twin lambs now making three kilos.

“We wean earlier and the lambs are heavier.

“I tell my staff to shift the mob when the legumes are eaten out, not the grass, that’s the key to growth.

“We really want to get the message out there as to the importance of the hill country and it’s legume content.”