Firing up the immune system

By Gordon Levett

About 20 years ago, I was discussing aspects of breeds of sheep with the worm-resistant trait with Dr John McEwan of Invermay AgResearch Centre near Dunedin. He surprised me when he said one day scientists would find the gene involved in worm resistance.

I commented that when this gene was found, it would mean the end of my work. He assured me that would not be the case.

I assumed we were talking about just one gene. Some 10 or so years later, talking on the same subject with Dr Jon Hickford of Lincoln University, he said there are many genes in the immune system involved in providing immunity to worm challenges.

Bearing in mind the previous conversation with Dr McEwan, I asked was it two or three? He said, maybe 10 and up to 20, and added, and some we may never find. Some of these genes may have other functions outside the immune system, he said.

So what appeared to be a simple matter of finding the gene involved, on further research, the immune system was found to be much more complex.

In all living species genetic variation enables all to adapt to environmental changes, be it climate change, or the dominance of a species. This genetic variation has enabled humans to “reprogramme” domestic animals to produce more of what they need in food; trees that produce superior timber; plants that provide better fruits, vegetables and grains. This same cornerstone of nature has enabled worms to evolve to become immune to chemicals designed to kill them.

The immune system also has genetic variation in its DNA that enables it to adapt to environmental changes. Selective breeding will shorten the time for the immune system to adjust. The bigger the change, the longer it takes to adjust.

Scientists and farmers have concentrated on improving the productivity of farm animals and have been very successful. But the importance of the immune system has been generally ignored. I find this strange because it is the key to good health and longevity.

The immune system can be slow in recognising and meeting disease and parasite challenges; it can be weak and fail to control them. Or it can quickly recognise and aggressively meet and overcome these challenges to forestall damage. This is genetic variation.

Breeding for worm resistance

The only way to breed for a more aggressive immune response that I know of, is to breed for worm or disease resistance like foot diseases and pneumonia. Probably breeding for worm resistance is the best option.

Counting worm egg numbers in a gram of dung gives a reasonable assessment of worm levels. Selecting a low faecal egg count (FEC) ram by the best sire for the lowest average FEC in his progeny, is a good first step. Mating this select ram with the daughters of another sire of progeny that also had an average low FEC will be a good second progressive step.

The more sires used, the better. I usually used 10 or 12 sires. Using three to four sires would slow progress, and small breeders breeding for this trait need to pool their resources to make more progress. Progress starting from scratch will be slow, especially if selecting for other traits which we have to do to have a saleable product.

It took me 34 years to breed sheep that have a moderate to high resistance to worm challenges, with most never requiring a drench, in a region of high Barber’s Pole worm challenge, with FEC averaging 4000 and over.

One key aspect of the immune system is that it is a fluctuating force with ebbs and flows. Good nutrition is essential for maintaining high immune responses. Times of low nutrition, as in a drought, a weakened immune system opens the door of opportunity for parasites and diseases. One of my father’s sayings was “skinny sheep breed lice”.

Play in the dirt

In a trial with children in England several years ago, it was found that the first three years of a child’s life determined the lifelong strength of the immune system. Dr Hickford knew this when he told me he had said to his wife their young children must play in the dirt at least twice a week.

Sadly farmers have had mixed messages on drenching over many years. Drench every four weeks. Leave some lambs undrenched to ensure the survival of the weakest worms. Now for my take on all of this. Early drenching of lambs is a big mistake.

Like young children, in the first four months of a lamb’s life they have to have worm challenges to fully activate their immune responses. Their immune systems are like a laid fire, ready to be ignited. In three or four weeks lambs will be nibbling grass and ingesting worm larvae. This will ignite the immune system like a match to fire.

Removing the worm challenge by drenching results in a pause in immune development. Another surge in immune responses will commence when worm numbers again increase.

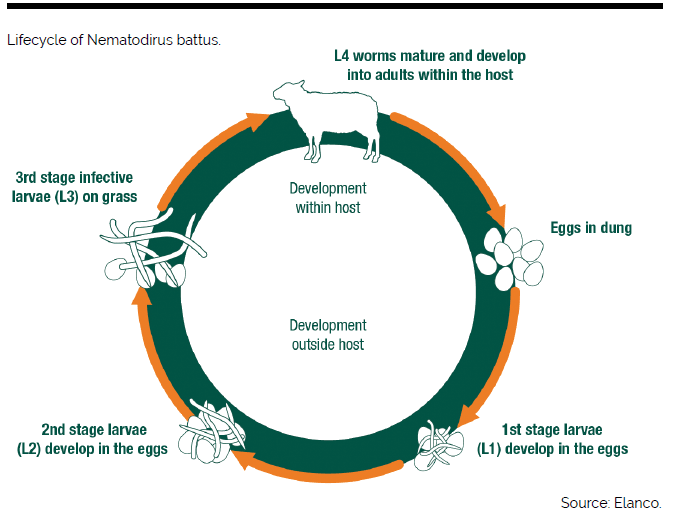

Like a fire, the immune system needs to be stoked. Continual challenges from diseases and parasites will ensure a vigorous response. Worm challenges are not great up to the middle of January, with the exception of nematodirus which is a problem in spring in colder regions. So lamb’s immune systems should be able to handle worm challenges until after weaning in most regions.

Lambs destined for the works may need more drenching. With ewe lambs, destined for the breeding flock, I would leave the best undrenched, run them separately or mark the drenched lambs.

When drenching ceases, the lambs with the least drenches could be top candidates for the breeding flock. Where the Barbers’ Pole worm is dominant, more attention is needed as lambs can die while in prime condition.

Bear in mind that the opinions expressed are based on experience and close scrutiny of 34 years of data, rather than the results of scientific trials.