Feral to flourishing

Terawhiti is on Wellington city’s boundaries and is one of New Zealand’s oldest farms. It also shares the wind with the Capital, with a power company generating electricity and income for the farm. Report and photos by Sarah Horrocks.

The howling, salt-filled nor-wester comes over the Tasman Sea and barrels through Terawhiti with formidable force. Everything shows signs of its presence — the trees are slanted, the dust has no chance to settle and the stock walk on a seemingly permanent lean as they roam the steep, uninviting hill country.

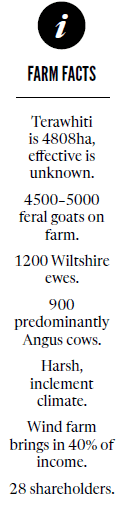

One of the oldest farms in New Zealand, Terawhiti Farming Company was founded in 1843 by the McMenamin family. Bounded by Wellington city to the east, the motorway to the north and 20km of the Tasman Sea’s coastline to the southwest, it’s a farming island, just a 20-minute drive from the Beehive.

In its heyday in the late 1980s, the 4808ha of mostly bush country was farmed by seven or eight shepherds on horseback, doing the best they could with 25,000 stock units (su) in a very challenging environment.

Managers Guy and Carolyn Parkinson came to the farm in 2009 when it was more than just a little run down, riddled with gorse and scrub, and home to only feral farm animals and pests.

“It was a real basket case,” Guy says.

There wasn’t a stock-proof fence on the place and Guy believes the previous managers had given up farming when they knew the wind farm was on the cards.

Meridian’s wind farm was being constructed as Guy and Carolyn arrived and it generates about 40% of the total farm income. That money comes from the land lease, plus a percentage of the total power generated.

“When we arrived the wind farm brought in 100% of the farm’s income.”

Guy says this was because in 2009 the only stock were 1200 mixed cattle, 250 sheep and an abundance of goats – all feral. Slowly but surely, a then 50-year-old Guy set about making drastic change.

The first job was a boundary fence, then he cut the place in half, and then into halves again. Paddock sizes still vary from 1700ha down to more manageable 15–50ha paddocks, but there’s been 70km of new fencing and 30km of upgraded fencing so far, all done by Gary Graham and, more recently, Scott Robinson, contractors from the Wairarapa.

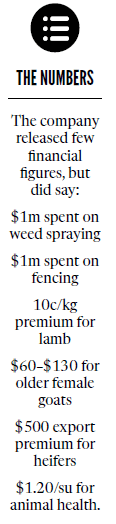

“Nobody has been game enough to add up what’s been spent on fencing but it’s in excess of a million,” Guy says.

He has nothing but praise for the guys doing the work. It’s stoney, steep and it’s inclement weather they’re working in. They’ve used a mix of seven- and nine-wire fences and find the windy environment is better suited to fewer battens and more wires. “The salt air rusts out fences within 15 years in the exposed places, but we’ll get 45 years out of them down in the scrub.”

Well-heeled goats

There are between 4500–5000 goats on the farm and 600–800 are killed annually at Kintyre Meats in Wairarapa to keep the numbers under control. They’re mustered into holding paddocks whenever the opportunity arises and all the bigger males and older females are culled, fetching $60–$130 each depending on their size.

“We try to manage the goats to some extent.”

Guy is adamant he needs the goats to control the weeds, which covered 75–80% of the farm back in 2009.

The goats live on blackberry, gorse, broom, thistles and other exotic weeds.

He admits they do eat grass at certain times of the year, which is why the numbers need to be controlled, but they don’t touch the natives.

“We’ve spent a million on spraying, but without the goats it would’ve been many million more.”

Guy believes the goats stretch the spraying out an extra three or four years as they control the regrowth exceptionally well. He even went so far as to breed domestic goats for two years and released them out with the feral population to better their genetics.

Genetics are also a big focus for the newly refurbished sheep and cattle operations.

Feral sheep beginnings

The original 250 feral sheep were all a ‘Romney-type’ and Guy culled all except 70 when he arrived. Over the next five years he bought ewes of every breed imaginable.

“I needed 800 so I just bought anything that was good buying to build the numbers.”

He had Texel, Romney, Suffolk, Perendale, Romney, Poll Dorset and more. However, the rams were non-negotiable, they were all Wiltshire from Morrison Farming.

Guy was aiming for an easy-care farming system, but after it took about eight years to get there, he says that in hindsight he’d buy in a straight Wiltshire flock if he had his time again.

“If you’ve got a good flock you’re better to sell what you’ve got and start fresh.”

Some of the Terawhiti sheep started shedding their wool at half-bred but others still held on to it at 7/8 Wiltshire. Even after 13 years there are still about 150 that need to be tidied up, but Terawhiti shepherd Ross Johnston takes care of those.

“It gets expensive if you’re paying a shearer to take a dollar of wool off a ewe,”Guy says.

With just Guy and his shepherd on the farm, he is adamant that Wiltshire is the way to go. There’s no dipping, dagging or docking, and very little shearing to be done. He believes there’s no more work in them than cattle and jokes that he doesn’t miss the wool cheque.

The Wiltshire rams that are bought in all have their tails intact because they’re trying to breed sheep that have a short, small tail.

“Markets are suggesting that we may not be able to dock lambs down the line, so we’re future proofing.”

Until now, the ram has been going out on March 10 for a late August lambing. However, the acquisition of a 190ha finishing block in Linton, managed by Luke Roberts, has given them some excellent finishing country for 1200–1500 lambs. This kinder country winters 2000su and will be able to take home-bred lambs earlier, so Guy plans to lamb 200 one-year ewes in July and send them to the Linton block in November.

Terawhiti dries out over summer, so the main mob can’t be lambing any later than August, with weaning in the first week of December.

“Ideally the cull ewes go then too, but we’ve had trouble the last couple of years.”

Guy hopes that the earlier November weaning will help with getting his cull ewes away on time and prevent them hanging around over summer.

Lambing percentages are genuine: ram-to-ewes to lambs-at-weaning. They don’t scan anything but they do bag them off as they set stock and any dries are sold. The lambing percentage at weaning over the past three years ranges from 100–135%.

Prior to buying the Linton block, all lambs were sold store through Feilding sale yards. Guy hopes they will now finish 20–30% themselves, with weights of 18kg CW coming off the Linton block last summer and targets of 18.5–19kg CW set for this summer and beyond.

“We kill everything through Taylor Preston as it’s right here, and we don’t plan to change that.”

Terawhiti is New Zealand Farm Assurance Programme (NZFAP) audited and guaranteed antibiotic free, so their lamb is rewarded with premiums of 10c/kg at Taylor Preston/CR Grace through the NZFAP and antibiotic-free premium. They also receive an additional 10c/kg for completing a predicted kill booking form every three months.

The sheep are run at a low ratio to the cattle. Terawhiti winters 10,000su – 85% cattle and 15% sheep. The goats aren’t factored in because Guy isn’t really sure how many there are, but he guesses there’s another 4500su on top.

This low ratio means drenching is an annual event for the ewes (pre-lambing), and the lambs are drenched six-weekly from weaning. The total animal health cost across sheep and cattle is $1.20/su.

“Our worm burden is low and we don’t have to worry about drench resistance.”

Sheep numbers sit at 1200 ewes, but Guy would like to lift that to 1500, which would see the cattle numbers drop slightly from the 900 cows.

Cattle a mixed bag

Like the sheep, it was a mob of liquorice allsorts with the 1200 mixed cattle back in 2009. There were 14-year-old bullocks, horned black bulls and every coloured beast you can imagine.

“There were some decent Hereford bulls on the place, but that’s about it.”

Guy sold all the old bullocks and cows plus anything else that was unproductive, and started from there. He then bought in 10 Angus yearling bulls from the Bay of Plenty.

“I wanted to go Angus right from the start.”

The Hereford bulls that were on the farm already were still used until they saw out their last days and the odd white face still comes through in the calves today.

Because everything had been mating all year round, it took three to four years to get everything calving at the right time and they still do have a relatively high percentage of dries.

“Anything that doesn’t get in calf or rear a calf is culled.”

Guy says this shows the great variation in cattle, especially with fertility. There are cows that have had a calf every year for 15 years and others that are down the road after just a single calf.

After buying those first Angus bulls from the Bay of Plenty, Guy sought out specialist Angus bulls for fertility, moderate size and short gestation.

“I’ve bought bulls from Ranui Angus in Kai Iwi for the past eight years because they’ve got the EBVs I’m after.”

The calving rates are slowly lifting, so the programme seems to be working, with the true rate of bulls-to-cows to calves-at-weaning at 80–85%.

Heifers aren’t mated until they’re two-year-olds, simply because there isn’t enough feed to get them up to weight for calving.

“We struggle to get the three-year-olds back up to weight to get them back in calf again.”

The bulls go out to the first calvers on November 11 and the MA cows are three weeks later. The first calvers are calved earlier and marked earlier, and put out into saved pasture. This gives them a slightly better chance of getting back in calf the second year.

As with the sheep, all progeny were sold as weaners in the store market up until last year, with the exception of their heifer replacements. Some heifers were sold into the export market. The premium of $500/head above the store market is lucrative for a yearling heifer sired by a registered Angus bull. Guy sold 56 in 2021 and 81 in 2022 to contracts with Australia Rural Exports, BeefGen and Southern Australian International Livestock Services.

“With the rest of the weaners we tend to get a good premium through the sale yards,” he says.

Most buyers are repeat customers due to the cattle being renowned for shifting well into any other environment, and they don’t seem to mind that the cattle are a bit lighter due to coming off such hard country.

“We don’t buy trade stock as anything we bring here struggles for the first 12 months.”

Now that they have the finishing block in Linton, Guy plans to finish a lot of the cattle progeny himself. This will mean a slight shift towards Ranui genetics as they have a bit more growth in the mix.

Inclement climate

The climate is harsh with hot, dry summers preventing growth for three or four months at a time in some years. This is balanced with mild winters that rarely see a frost, allowing good growth through the cooler months.

Guy is adapting the pastures to add in more drought-tolerant clovers, plantain and chicory, but the fact that 90% of the farm is steep hill country doesn’t make this easy.

“We broadcast seed over the better hill country with the fert.”

So far he’s been using a mix of clovers and ryegrass on the hills. On the 100ha Guy can get a truck over, he’s broadcasting cocksfoot, plantain and chicory, which is having varied results.

“The plantain looks better than the rest, but mostly we’ve found it doesn’t really persist.”

The soil is in pretty good condition, all things considered. Guy only puts phosphate on and a bit of sulphur when needed. Last year it was flown onto the better country (about 800ha) at a rate of 250kg/ha. This is done every two years and the soil testing shows the Olsen P levels at 21–22 on the better country, a big shift from levels of four when Guy arrived. The pH sits at about 6-6.5.

The 100ha of flat land gets broadcast fertiliser every three years at a rate of 450kg/ha.

Up in Linton, the programme is slightly more finely tuned. Guy has lent 11ha to a dairy farmer neighbour for a barley crop. It will be harvested in February and the dairy farmer will take the crop and regrass/fertilise it for Guy with a summer-tolerant grass crop.

“If that works we will look to do a paddock every year as we work around the farm.”

The Linton block was a dairy runoff previously, so it’s had plenty of fertiliser in the past, with Olsen P levels of 20–25 and a pH of about 6.5.

Trees matter

The native environment at Terawhiti is nurtured by Guy and Carolyn, both self-proclaimed ‘eco-warriors’.

“We don’t like pine trees and we don’t need to.”

Native canopy covering 1800ha is registered in the ETS for carbon credits and while Terawhiti receives good returns on that, they’re yet to cash in any of the credits. It’s all newly planted (post 1990) and has the potential to grow to a five-metre canopy.

Manuka has a large presence on the farm, covering about 2000ha and increasing all the time.

Carolyn has a nursery that produces about 800 manuka seedlings every year and they’ve now planted out about 7000 manuka plants on the farm.

“I grow them from seed, but they’re really hard to grow and get established,” Carolyn says.

Guy refers to a beekeeper who planted 4500 seedlings a few years back. Almost every seedling was lost in the first summer, but Carolyn’s seedlings seem to have better luck when planted out earlier.

Kapiti Honey places 352 hives across the property, paying a hive price that contributes about 3–4% to the total farm income. The sophisticated roading network on Terawhiti makes work a lot easier for the beekeepers, thanks to the myriad of sealed roads across the farm put in by Meridian.

“The wind farm is a great source of income but equally valuable is the roading network it’s given us,” Guy says.

When he arrived they only used horses and it took two hours to get to the back of the farm. Now they can get around the whole farm in a ute within 20 minutes and they’ve also been able to put loading yards in the middle of the farm.

The bottom line

The ownership structure is pretty simple with 28 shareholders at Terawhiti, all of whom are direct descendants of the McMenamin family, except Guy and Carolyn who only recently invested in the company. The shareholders are paid a fixed percentage of the gross profit as a dividend each year.

The ownership structure is pretty simple with 28 shareholders at Terawhiti, all of whom are direct descendants of the McMenamin family, except Guy and Carolyn who only recently invested in the company. The shareholders are paid a fixed percentage of the gross profit as a dividend each year.

Calculating the production per hectare is almost impossible, mostly due to Guy not exactly knowing how many effective hectares there are.

“It’s roughly 2000ha effective, of varied effectiveness.”

He says that while Terawhiti is one of the least productive farms in the country, it would be one of the most profitable, mostly due to the low input system and income from the wind farm. Beef brings in 35%, sheep another 10% and the remainder is made up of tourism, rental properties, goats, honey and carbon.

“We operate on the principles of diversification, sustainability and resilience.”

While Guy jokes that he’s created an old man’s farm that doesn’t require any hard labour, at the same time he knows the hard yards have been done and he’s now able to sit back and enjoy it a bit more.

A lot of Guy’s workload now involves doing the budget and then liaising with the board of directors, all non-farmers, who leave the farming and the market decision-making to Guy.

“Between us we can manage most of the compliance and regulations that are thrown at us these days.

Being close to the city does mean a lot of extra red tape and regulations, but the plus-side to Terawhiti’s location makes it a pretty desirable place to work. You’ve got tar- sealed roads to the door while still getting free access to hunting, diving, fishing and plenty of gale-force fresh air.

“Watch the door!”

Diversification

While the roading makes farming a lot easier, it has also opened the door to opportunities in tourism. Pre-Covid there were tour groups of cruise ship passengers coming out to Terawhiti for a tour around the farm, to hear about its history and have a cup of tea at the original homestead on the coast.

“All we had to do was give them a key to the gate and we took a fee for every head that went through.”

It took a few years to build it up and it was just starting to take off as Covid hit, which of course decimated the operation. Guy and Carolyn hope this will get going again now that the cruise ships are starting to come back to Wellington.

The general public like to help themselves too of course, which causes a few problems, but in general everyone is happy with their fishing, biking or walking along the Queen’s Chain, admiring the cattle chewing on seaweed in the bays. Guy says most people are pretty good and play by the rules that are clearly written on the entry gates.

“There are a few poachers and hooligans that spoil it for the rest of them.”

With the great reduction in staff numbers came an abundance of empty houses on Terawhiti and most are now rented to city folk as weekend baches on a semi-permanent basis.

“Once people get hold of them they never want to part with them,” Guy says.