Tom Ward

The last six months in South Canterbury have thrown up some interesting and contrasting scenarios on the hill country.

First, the spring/early summer has been very different from 2018 where a huge amount of silage was made early, right through to Christmas, at great cost and of often questionable quality. Crops were difficult to get in and some were drowned, with most having reduced yields.

No sooner was the silage making over than the big dry caused much of the conserved feed to be fed out.

Second, many hill country sheep/beef/deer farms had a lot of dry low-quality feed to deal with last autumn, which was not only crappy tupping feed but pretty much useless as a winter feed.

Winter feed crops were down 10-25% in the case of kale, and some fodder beet plantings were totally ruined (drowned) especially on the flat. Fortunately, the winter was warmer through to May so crops caught up a bit.

Fodder beet sown on slopes and by direct drilling fared better and were better utilised. Where it was not possible to sow or re-sow before January, swedes were planted and proved a cheap alternative to beet, still yielding up to 10 tonnes drymatter (DM)/ha.

Farmers are thinking forward to such matters as whether there will be enough surplus to make silage, how to manage paddocks to be taken out for next winter’s crop, how they will optimise lamb income, and breeding ewe body condition scores.

Surprisingly, much of the poor-quality pasture seemed to have rotted away by the spring, nevertheless pasture covers were low at the start of lambing and have remained that way since. One solution, for those monitoring carefully, was to graze mixed age ewes and/or ewe hoggets off-farm for all or part of the winter on South, Mid or Central Canterbury cropping farms.

The province has had few major storms to decimate new-born lambs, however regular snowstorms in the mountains have held back soil temperatures and pasture growth into October. Lambing percentages are reasonable, maybe back 10%, and breeding ewe condition is variable as are lamb growth rates.

So, there is no absolute disaster, but most are short of feed. Farmers are thinking forward to such matters as whether there will be enough surplus to make silage, how to manage paddocks to be taken out for next winter’s crop, how they will optimise lamb income, and breeding ewe body condition scores (BCS). A conclusion to the paragraph above could read: “there is a lot going on at a time when the farm will often be drying out”.

Taking each topic separately and dealing with the silage question first, grass should only be conserved if there is a genuine surplus.

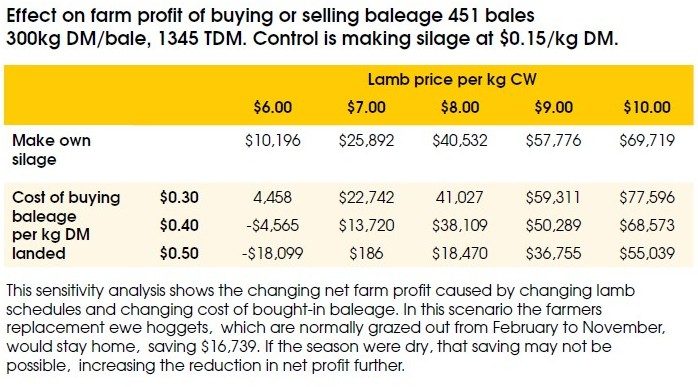

With home-bred lambs earning between 20 and 30c/kg DM and the cost of bought-in bailage 30c/kg DM in a “normal’ year, you are better to feed good-quality grass to the lamb rather than make silage if there is not a genuine surplus. However, in a drought, the cost of supplement will be 50c/kg DM (or more), so in a year where there is a large surplus of grass, the lambs should be marketed at the normal time and surplus grass conserved, if possible, as silage to be used in a tough year.

With home-bred lambs earning between 20 and 30c/kg DM and the cost of bought-in bailage 30c/kg DM in a “normal’ year, you are better to feed good-quality grass to the lamb rather than make silage if there is not a genuine surplus. However, in a drought, the cost of supplement will be 50c/kg DM (or more), so in a year where there is a large surplus of grass, the lambs should be marketed at the normal time and surplus grass conserved, if possible, as silage to be used in a tough year.

Winter crop paddocks can be timed to be taken out at the same time as weaning and sale of the first lambs. This particularly suits kale for sheep. Also, silage paddocks should be coming back in, or if feed is short, not dropped out at all. Fodder beet, especially on a small farm, can be very problematic in this regard (old paddock still out when new one being prepared), and in the view of many farmers a disincentive to do too much cropping. Having said that, the ability to use beet in October might help deal with a tough spring. Each farm needs to do its own analysis.

The last topic, ewe BCS, is often neglected, however some farmers are using BCS as the basis for all decisions. BCS is as important as feeding in driving lambing percent and lamb growth rates, so farmers need to be conscious at all times that their ewes will be in the right condition at tupping and lambing. Having every ewe at a BCS of 3 and planning how the animals will be managed to achieve this BCS, drives the detail.

Ewe hoggets can be used as a buffer, with this stock class being grazed off if feed is very short or mated as lambs if there is sufficient feed.

So, in practice, managing a hill country farm, particularly where there is little cultivable land, is difficult. In New Zealand we have traditionally used the breeding cow to buffer feed shortages or absorb large quantities of poor-quality feed on this type of farm. Where there is optimum subdivision and/or stock water supply is piped to troughs, more-efficient dry cattle can be used for this purpose.

Some farms are successfully using short-term feeds to supply additional feed in late spring. These include prairie grass, red clover and annual ryegrass which will grow faster than perennial ryegrass-white clover pastures in early spring, however they need to be spelled to allow a feed bank to build. In late spring, lucerne, which responds to air temperature, can also be a valuable source of grazing feed.

Using bagged nitrogen, either as urea or sulphate of ammonia, is a quandary for me. Applying it pre lambing (early August) is generally too soon in the South Island with soil temperatures often less than 6C. Furthermore, waiting until late August or September, when the soil temperature has risen to 7-8C, limits the response due to pastures being constantly stocked (set stocked) with sheep during lambing.

Competent farmers understand that managing constantly changing feed scenarios is not what they do as farmers, it defines them as farmers (climate change enthusiasts have no idea). If you can get your head around this fact, and embrace it, you will have a very profitable and satisfying farming career.

- Tom Ward is an Ashburton based farm consultant.