Exciting future for farming

Graham Butcher sees potential for improvements if farmers take a step back and look.

Graham Butcher sees potential for improvements if farmers take a step back and look.

In my book, sheep farming is an exciting industry with a future. Yes, we see challenges from central Government regulation, policy and carbon values nipping nipping at our heels but we also see significant cohesion in pushing back at a level possibly not seen before. And it seems to be registering.

“Rural rage moved into the cities as farmers mounted protests against Government policy,” reported the Southland Times. No, not July 16 this year but March 11, 1986. Different issues back then of course. It would seem each generation of farmers reaches a tipping point where enough is actually enough.

Pragmatic solutions will, I believe, prevail and we will still be farming sheep in 2060 and come to know that the environmental compass points, currently suggested, needed to be addressed. Who would now say that those 1986 issues, being addressed, have not strengthened farming?

As for carbon values destroying food production – there are challenges right now with rocketing carbon value. Two things though, you can’t eat carbon and if food production world wide falls because of land being swallowed up by permanent trees then food prices must rise. This should pressure governments to act and act as a counter measure to bring balance to the equation. Expect some, hopefully, short term disruption though.

So, the way ahead looks exciting. You can look at this on a couple of levels. First we have the day-to-day management of sheep and the potential improvements there for the taking. These are things you could think about today and implement tomorrow and see a benefit in the current season or at least in the next season.

We all hear about the “top 10%”, some of their performance will be based around physical farm attributes and some will be based on just how they go about making policy decisions. These folk also have the ability to step back and take a critical look. “If your lineout isn’t working, step back 20 metres and watch.”

To cover off all the things that could result from this “step back and watch” could fill a book, but here are some of the more fundamental ones. I’m a bit Southland-biased here but you will get the idea.

- High per head performance is very important – talking reproductive performance and young stock growth rate. If there are issues, sort them out today. What’s really holding things back? A deceivingly simple question but the most important one.

- Stocking rate – this is fundamental. Each farm will have a sweet spot as regards per head performance, winter feed costs, control of summer quality and being able to manage what can be vastly different seasons.

- Never take mob averages (condition scores, LW, etc) as an indication of success. Look more at the spread and always look at how you can deal with the bottom 20%.

- A key target is average pre-winter pasture cover. If you don’t get this right you are in trouble. Possibly more a Southland issue but other parts of the country will have equally critical periods.

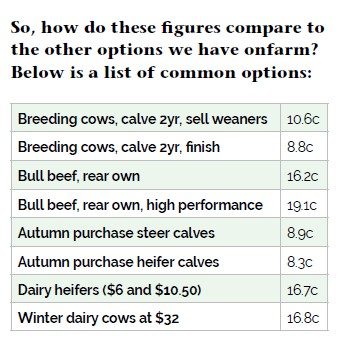

- Combining enterprises, notably breeding cows, can have benefits, particularly hill country farms. This is not about substitution, it’s about running a class of stock that will better deal with lower quality surplus feed that might otherwise be wasted. On this note, a lower profitability enterprise can still lift farm performance.

- While dealing with strategy issues (stock policy) don’t forget the basics, like dealing with selenium. A white board in the office is great. You can write down these sorts of things.

- A second opinion can open up new avenues for thought. Sometimes the obvious can be missed if you have been doing it for 10 years.

- Once a plan is made, make sure you carry through with it and expect to have to make some revisions. This is called progress.

Big gains are to be made from getting the basics right – so that’s exciting.

Long-term what might need to happen in the future to deal with rising costs, greater consumer demands, legislation/regulation and the ever-present stock welfare.

Occasionally something comes along that turns “conventional” sheep farming on its head. Sheep milking is a good example.

Cows to sheep milking

Who would have thought we would have conventional dairy farms in the North Island converting to sheep milking. Not many, but it’s happening. Milk is the most valuable product a sheep can produce, and we still get wool, lambs and cull ewes. It’s had a 35-year gestation, with failures, but it has now found its feet. So congratulations to those who trusted their research/intuition and persevered.

The next one to touch on is aseasonal breeding. We are well and truly wedded to short day mating and once a year. It’s serving us well but there are possibilities here. Changing climates are altering the feed supply pattern and premiums for “out of season lamb” are attractive. We have breeds here that will ovulate just about any time of the year so we need to recognise this as an opportunity.

A significant add-on to aseasonal breeding is mating every eight months – that’s three lambings in two years. Not a new concept, it’s been around for a while both here and overseas.

I was involved with some trial work with Polled and Horned Dorset, nearly 20 years ago now, on a farm close to Lawrence. Not the ideal farm, it’s in the deep South with long cold winters, but that’s where the ewes that we needed were. We at least showed it was a feasible proposition.

To establish such a system, you need to construct a new management system from the ground up and have a more conducive climate than the deep South. The fundamentals make sense, lower ewe numbers, higher numbers of lambs, more feed directed towards growing lambs.

Next we have production of higher eating-quality lamb. We have the Alliance programmes such as Pure South Handpicked, Te Mana and Silere all aimed at eating quality. This is the right approach and represents an opportunity.

A while ago I came across information about Australian White sheep, touted as the Wagyu of the sheep world. It’s a synthetic cross between Poll Dorset, White Dorper, Texel and Van Rooy. It apparently has a very high intramuscular fat IMF and low melting point fat – both important for eating quality. Needs to translate into value at the farm gate of course. If it can, expect to see changes in this direction.

Interestingly, Australian Whites are a hair sheep, no shearing, which leads me on to the next point.

The vexed issue of strong wool. Opening sales for this season look promising, if these hold we are probably in a position where there might be surplus funds from the wool cheque once shearers are paid. Farmers know that wool’s attributes (sustainable, non toxic, fire retardant) are valuable. The rest of the world just needs to catch up with us. My view, I think the world is catching up slowly.

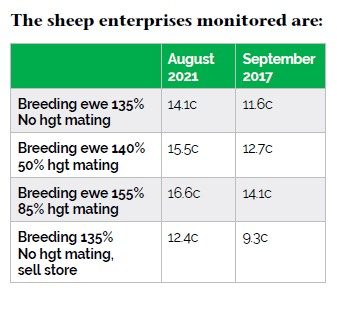

Latest gross margins

I have just updated the gross margins based on c/kg drymatter consumed. This gives a broad comparison between how different enterprises can convert a kg DM into profit. It’s based on average pricing/costs and, as always, there will be those that can buck the trend and can command a better return.

So, despite wool, we have appreciating profitability. It’s of interest to note that the initial 2021 wool sales show strong wool still has a heartbeat and if we can recover to the 2017 average greasy price of $3.17, we will add about 1.2c/kg DM to the gross margin.

I know that doesn’t sound much, but we are dealing with nearly 2.1mkg DM for the 2458 ewes/688 hoggets and 38 rams modelled.

- Graham Butcher is a Gore-based farm consultant.