Erosion-prone land brings pine profits

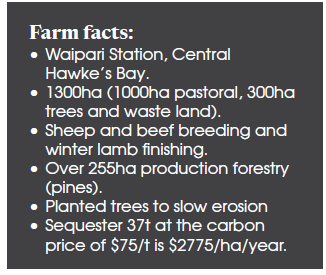

While sheep and beef are the focus of Waipari station, trees to protect eroding land bring in the money, Russell Priest writes. Photos by Brad Hanson.

While sheep and beef are the focus of Waipari station, trees to protect eroding land bring in the money, Russell Priest writes. Photos by Brad Hanson.

M ark Warren doesn’t like pine trees, but he does like the returns.

Faced with alarming erosion on his family’s 1300 hectare (1000ha effective) Waipari Station, 33km southeast of Waipawa, Mark planted trees in 1983 to address the problem.

For the last 40 years he has been reaping the benefits – not just slowing erosion but the financial gains.

Predominantly a sheep and cattle breeding and winter lamb finishing enterprise, Waipari (meaning the place where the water runs out of the hill) is tough coastal hill country rising from near sea level to 444 metres. It’s prone to prolonged droughts and intense easterly storms, while nor-westerly winds can be equally destructive.

Contour is 25% flat to undulating, 60% strongly rolling to moderately steep and 15% steep to very steep while soils are derived from crushed argillite and soft mudstone and consist of 75% clay loam, 13% silt loam, 11% sandy loam and 1% other soil types.

Annual rainfall varies between 1200-1500mm a year with most arriving from the east and the majority falling in winter and spring. The station is well balanced in terms of aspect.

A total of 270ha of about 300ha on Waipari not regularly grazed by livestock is planted in pines and other trees.

About 110ha of trees are in the Emissions Trading Scheme (ETS).

Waipari has been in Mark’s family for 140 years, bought by his great grandfather Reverend Samuel Williams in 1880. Mark was raised in Geraldine, South Canterbury, the son of an Anglican minister.

From an early age he was interested in farming and after leaving school, he worked on stations in Canterbury and the Mackenzie Country. He gained an agricultural diploma from Lincoln, spent 18 months as a diesel mechanic and even juggled working on a Canterbury cropping farm with being a professional ski patroller. Having always been run by managers, Mark was the first family member to assume a hands-on role.

In 1982 Mark took the opportunity to work on Waipari with a view to managing it for the many family stakeholders. He was appointed manager in 1983 at the age of 24 to a business which was financially in trouble. Three weeks after taking charge David Lange became prime minister and Rogernomics was about to present Mark with further challenges.

The station had only three stock-proof paddocks (now more than 120) and no fertiliser had been applied for three years. The previous year’s lambing percentage was 56%, calving 60% and farm working expenses represented 99% of the station’s gross farm income. But Mark was fit, determined, and prepared to think on his feet while constantly working 14-16 hour days.

“However, being dyslexic I often do things in a different way to a lot of other people,” he says.

He quickly recognised the precarious state of a significant percentage of Waipari and in spite of having little money, Mark planted 70ha of pines in 1983. This was harvested in 2007/2008.

Gullies fill with silt

“While I’ve been here I’ve seen whole gullies fill up with silt so some of the early plantings were with poplars and willows and that was hard going.”

Mark reasoned that planting production forestry not only slowed erosion but provided a financial buffer if pastoral farming was threatened by the likes of foot and mouth. What’s more, trees grow particularly well in the crumbly mudstone. After a year in the ground they can withstand the dry summers whereas pastures can struggle.

“Our soils can produce oversized pine trees in 24 years, and if you plant the right genetics the trees have excellent form.”

About 85ha is in first rotation radiata pine, 170ha second rotation, 8ha is in Tasmanian blackwood, 4ha is in lusitanica, 0.5ha is in macrocarpa, 0.5ha is involved in a ground-durable eucalyptus trial and 2ha is in natives under a QEII covenant. Mark believes the area in trees could expand to 350ha.

What appeals to Mark about trees is not only their financial viability but their low labour requirement.

‘Once they’re planted you just sit back

and watch them generate about $1000/ha/ year.”

While the ETS tables show pine trees sequester carbon at 26 tonnes/ha/year, trees in his area were doing 37t which on the carbon price of $75/t represents $2775/ha/ year.

He also cites a 20ha block of pines planted on extremely unstable Waipari country – when harvested, they netted almost as much as the GV of the whole station at the time of planting.

Waipari’s economic farm surplus from its livestock enterprises of $450/ha/year (in a good year) pales in comparison with the forestry figures in spite of the sheep and cattle being run on the best country (class 4/5).

Mark has a predetermined price for harvesting his pines. He’s established that the most cost effective area to harvest is 30ha every three years.

“Shifting high performance harvesting gear around costs $20,000-$30,000 so to justify this a reasonably large area needs to be harvested,” he says. “But by the same token anything larger is too big to plant and tend at once and too large an area is lost for grazing.”

Establishing pines can’t be grazed for two years after planting. Shorn hoggets can graze a newly planted area after two years, ewes after three, young cattle after four and other cattle after five.

Wide-spaced planting of poplars on steep areas within a paddock where the easier contoured areas can be cultivated is another area of interest. Mark believes areas with sheep tracks should not be cultivated as they are inherently unstable and planted in poplars instead.

Poplars provide shade and feed

He cites the benefits of poplars as shade and feed for stock when in leaf, the ability to access nutrients deep in the soil, and once the leaves have fallen the grass beneath them provides valuable winter/spring feed.

They also sequester carbon at about 20t/ ha/year (average over 10 years) and at $75/t this represents a potential return of $1500/ ha/year in carbon credits. However, as Mark points out, any business created by the stroke of a pen can be deleted with a stroke of the same pen. He views carbon credits as a form of rural bitcoin.

These days, Mark has adopted a hands-off approach within the operation. Day-to-day running has been handed over to the management team of Adam and Holly Price. Mark gives Adam a reasonably free management brief but he still plays a major role in marketing stock to optimise their returns.

“You’ve got to reward good managers not only financially but also with responsibility so they can put their mark on a property.”

Under the Livestock Incentive Scheme ewe numbers on Waipari had risen to 8000 before Mark took charge. These were quickly dropped to 6000 with the lambing percentage increasing to 100.

Today Waipari winters 4000 Romney ewes (at an average lambing percentage of 150) based on Te Whangai (De Lautours) bloodlines, 4000 hoggets, 40 rams, 270 Angus Hereford cows (including R2 heifers), 100 R1 heifers, 100 R1 steers and 15 bulls.

An interesting feature of the station’s livestock business is that only a few Romney lambs are killed off their mothers.

“Even if we have a good spring like last year and we get lambs up to weight they just don’t yield. Our country is just not good enough at present to finish a significant number of stock off pasture so we leave it to those that are better at doing it.”

Instead Waipari markets its lambs in several ways. It has been a supplier member of Atkins Ranch since 1990, so lambs are killed off crops during the winter and spring at 22-24kg carcaseweight returning up to $230/head. An increasing number of the terminal-sired lambs along with their cast-for-age mothers are sold in the spring as ewes with lambs at foot.

“This way we don’t have to worry about getting rid of the old ewes after weaning.”

Waipari is the first sheep farm in the world to achieve G.A.P. 4 accreditation (an animal welfare market standard that requires proof that sheep live on pasture throughout their lives) and more recently it was one of 22 farms in NZ to gain regenerative farming certification from the Savory Institute via a pilot programme through Atkins Ranch. Both these add significant value to its lambs when sold through Atkins Ranch.

Waipari runs a two-flock system with about two thirds of the ewes (A flock) going to Romney rams and a third (B flock ewes) to terminal sires. Mark calls the latter the “old and uglies” because they represent all the one-year ewes plus any ewes deemed unfit to breed replacements from.

Mated to Kelso terminal sires on March 1, these ewes are lambed on the earlier coastal country with many of the one-year ewes being sold with lambs at foot in late October/early November. This frees up land for the remaining B flock ewes and their lambs enabling between 300 and 400 to be drafted off mum at an average of 17kg CW. No terminal lambs are docked.

“This system suits the early country and generates valuable cash flow. We’re working towards selling all one-year ewes with lambs at foot.”

Rams must be easy care

Ram-out date for the A-flock MA ewes is April 1 and two-tooths April 15. Rams are out for 2-2½ cycles at an initial ratio of 1:100 but some rams may be pulled out in the second cycle if low in condition or there is excessive fighting.

Mark entrusts Hamish de Lautour to select his Romney rams but specifies they must be structurally sound, have a background of easy care with some worm resilience as well as good survivability and fertility/fecundity.

Ewes are scanned for singles, twins and dries with all dry-dries being culled. Replacement two-tooth ewes are selected from ewes scanning twins.

“I’m seriously questioning the value of scanning because it’s hard on the ewes and labour and expensive. It’s useful when

Left: Lambs on coastal finishing country looking south. Below: Young pine trees.

feed is tight and for separating single and multiple-bearing ewes for lambing, but I’ll leave the final decision to the manager.”

Average lambing percentages are around 160% for the MA A-flock ewes, 140% for the two-tooths and 135% for the B-flock ewes.

“We’re never going to get as high a percentage in the B-flock because it’s mated a month earlier, however that’s the trade-off if you want early lambs.”

The steeper, harder country is home to the A-flock ewes during lambing and because they are genetically selected to be easy care no lambing beat is carried out.

Romney lambs are generally weaned in early January and drenched, crutched and fly-dipped. If feed is plentiful, they are reunited with their mothers on the hills as Mark believes they do better if they have access to milk for as long as possible before weaning. At weaning some lambs are put on crops of raphnobrassica, lucerne/clover, plantain/clover/chicory and others on pasture. Ewes are shorn in January as are sometimes the ewe lambs in February.

“We’re moving into more of a lower-cost, simpler model of farming so we won’t be sowing as many crops as we have in the past.”

Growing at a moderate rate the unshorn, undocked Romney male lambs are killed progressively through Atkins Ranch from June through to November.

“We don’t shear our lambs because it’s more cost-effective to shear them when they’re almost a year old. What’s more, research has shown they grow just as well in the wool as they do out of it.”

Lambs are assembled in groups of 200-300 based on their weight. Starting with the heaviest the groups are in turn introduced to winter-active forage barley (ME 13 – sown in March) at 15/ha which accelerates their growth rates (up to 700g/day) before being killed at 23kg CW ($220-$230).

Hogget mating is not practised as getting them up to a satisfactory mating weight and doing them well through to two-tooth mating is too difficult given that nearly all Romney lambs born are retained over the winter.

Crossbreds grow faster than pure Angus

Waipari runs 270 Hereford Angus-cross breeding cows including in-calf R2 heifers. Mark believes the crossbred progeny grow 7% faster than pure Angus.

“We used to run 500 cows but had to spend too much time feeding hay which wasn’t cost effective, was dangerous and wrecked the soil so we’re now a half breeding, half store cattle operation. This country’s warm in the winter so you’re better to feed just grass.”

The store cattle act as the station’s safety valve. All weaners are wintered with R2 steers being sold as forward stores in the spring/autumn depending on the feed situation and cull 2yr heifers are killed for local trade. Waipari also has a share-farming arrangement with Poukawa’s Bill Buddo whereby animals are valued before they leave Waipari and the value added at Buddos is shared.

Maintaining pasture quality and cleaning up roughage over the winter is the cows’ role. Bull-out date for cows and R2 heifers is November 13 with bulls left out for two cycles achieving an overall calving percentage of 88-90% (cows scanned in calf/calves weaned).

Besides structural soundness Angus bulls are selected using both the AngusPure Index and the Angus Self-Replacing Index while the Hereford Prime and Export indexes are used when selecting Hereford bulls.

Heifers have been mated to Wagyu bulls for the last two years and while this has virtually eliminated any calving problems the progeny have been difficult to market and can be a bit temperamental.

“We run all suitable 15-month heifers with the bull and nature decides which ones get in calf.”

Cows are calved on the hills while heifers are calved on grass behind an electric fence which is shifted twice a day.

“I find if they are given a small break in the morning and a larger break at night they tend to calve during the day and spend the night eating.”

Calves are weaned in late March/early April at 270-280kg however if there is an abundance of feed they are left on the cows for as long as possible.

Waipari is well served by an extensive laneway system, satellite yards and excellent all-weather tracks designed to accommodate heavy vehicles carrying logs. Olsen phosphate levels range from 22-25 while pHs lie between 5.8 and 6.0. Average annual fertiliser application is 250kg/ha of super.

“We poured a lot of fertiliser on at 300-400kg/ha when it was cheap (less than 2 lambs/tonne) but this year it was too dear so we’ll hold off applying any more until the price comes back. Our fertility levels are pretty good.”

Mark operates two separate businesses; Waipari Forestry Ltd. and Waipari Station Ltd. and also runs a four-wheel drive consultancy company Hillseekers 4WD NZ Ltd. In 1992, Mark was awarded Hawke’s Bay Sheep and Beef Farmer of the Year achieving a 15.9% return on capital.

Being an entrepreneur, Mark has developed numerous businesses in his lifetime one of which was selling bottled water from springs which emerge from limestone country on Waipari at 425m asl. He has even written a book entitled “Many a Muddy Morning”, which records the extreme challenges of surviving, and thriving under Rogernomics. His latest project involves developing a rocket-launching pad on Waipari on a site near the sea.

Mark has four children; Emma (32), William (25), Henry (24) and Jacko (22). Henry works on Waipari with Mark and has been joined this summer by Bridgette Haldane who is completing part of her practical requirements for a BAgSc at Massey University.