Tony Leggett

Experienced agricultural economist Rob Davison has unearthed a concerning consequence for forest landowners, including farmers, from government policy on climate change.

The Beef + Lamb New Zealand Economic Service executive director’s analysis suggests a massive loss in equity awaits farmers and other landowners who choose to plant large areas of pastoral land in trees and sell off carbon credits.

The impact hits after the first rotation of trees is harvested, usually about 20-25 years. At that point, there’s an obligation in the legislation to replant the land in trees. However, landowners are unable to sell any carbon credits on that second rotation of trees and only receive income from the harvested trees 20-25 years later.

“The other thing that is obvious is that you’ve given up your property rights because you’ve committed that land to be replanted,” Davison says.

“Cut-over forestry land next door to sheep and beef farms is currently discounted in value by 50-60% because it has to be replanted back in trees.”

Davison says that loss of equity for landowners would be catastrophic for many farming families and financiers. He’s also concerned that if NZ reaches its goal of being carbon neutral by 2050, the market for carbon credits will also fall to very low levels, further reducing the returns to landowners.

“And, I wouldn’t bet on log prices in 50 years’ time either if we continue to plant large areas of hill country in trees,” he says.

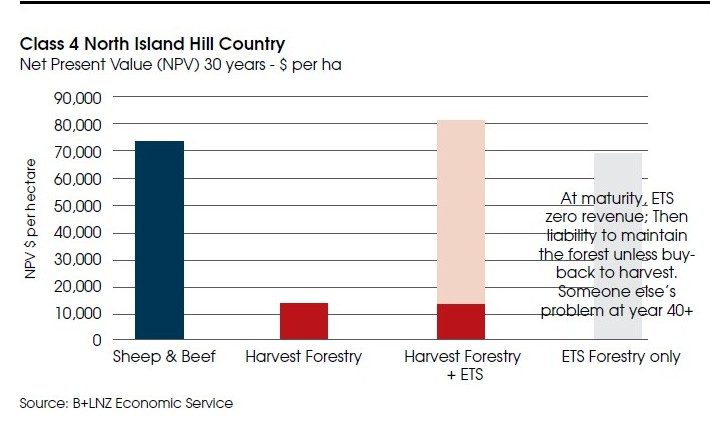

Using a net present value analysis technique to discount 30 years of future income and costs back to present day values, carbon farming competes well with efficient farming of sheep and beef cattle on hill country for the first rotation.

But as the graphic shows, after the first harvest of logs, the net present value drops back to log price only and the return is less than a quarter of sheep and beef farming on class 4 hill country.

For his analysis, Davison used the 2017-18 earnings before interest, tax, repairs and maintenance for sheep and beef of $506/ha, log price of $140/tonne, the Treasury discount rate of 6% per annum and a carbon price of $25/tonne.

“Sheep and beef land is up at a bit over $7000/ha, harvest forestry is down at $1500/ha which confirms why we don’t have forestry all over the whole country. I’m very happy as an ag economist to see this result.”

He acknowledges that harvest forestry plus selling carbon credits competes strongly with hill country sheep and beef farming and accepts that if the carbon price went to $30/tonne from the $25/tonne used in his analysis, its net present value would easily outstrip livestock farming.

But the future impact after that first harvest resulting from the commitment to replant with trees reduces the net present value substantially.

At maturity (of the second rotation), the emissions trading revenue is zero and the landowner has the liability to maintain the forest. Or, they could choose to buy back the credits sold and harvest the trees.

Davison says, after 40+ years, it will be “someone else’s problem”.

He’s urging farming leaders and the Government to consider the impacts of further largescale tree planting on productive farmland.

“Think about this for a moment, 90% of our livestock production is exported. If you put a million hectares of hill country in trees, you’d probably say that’s all going to go to export too.”

“But if we’re going to just plant trees and go with the ETS, it’s 100% NZ dollars. Effectively we’ve turned an export hectare into an import hectare and we’ll take out about $1.25 billion of export receipts lost from not exporting meat and fibre.”

“So, when Pharmac goes to buy medicines or the government buys more electric cars for its fleet, there’s fewer NZ export dollars coming back in and a lot more bidding to go out.”

“What happens then is our dollar will go down which is not bad for those who stay in farming. I’m just saying these policy issues need more thought,” Davison says.

Beef + Lamb New Zealand favours a farmer-led approach to achieving carbon neutrality, as well as protecting biodiversity and fresh water, and controlling erosion on farms. He Waka Eke Noa is a five-year work plan to be developed in partnership with sector groups. It includes measurable actions, outcomes and time frames that facilitate and support action on environmental improvements,

including climate change impacts. The

aim is to ensure a fair and effective farm level pricing mechanism is designed for GHG emissions.