Drought prompts rethink

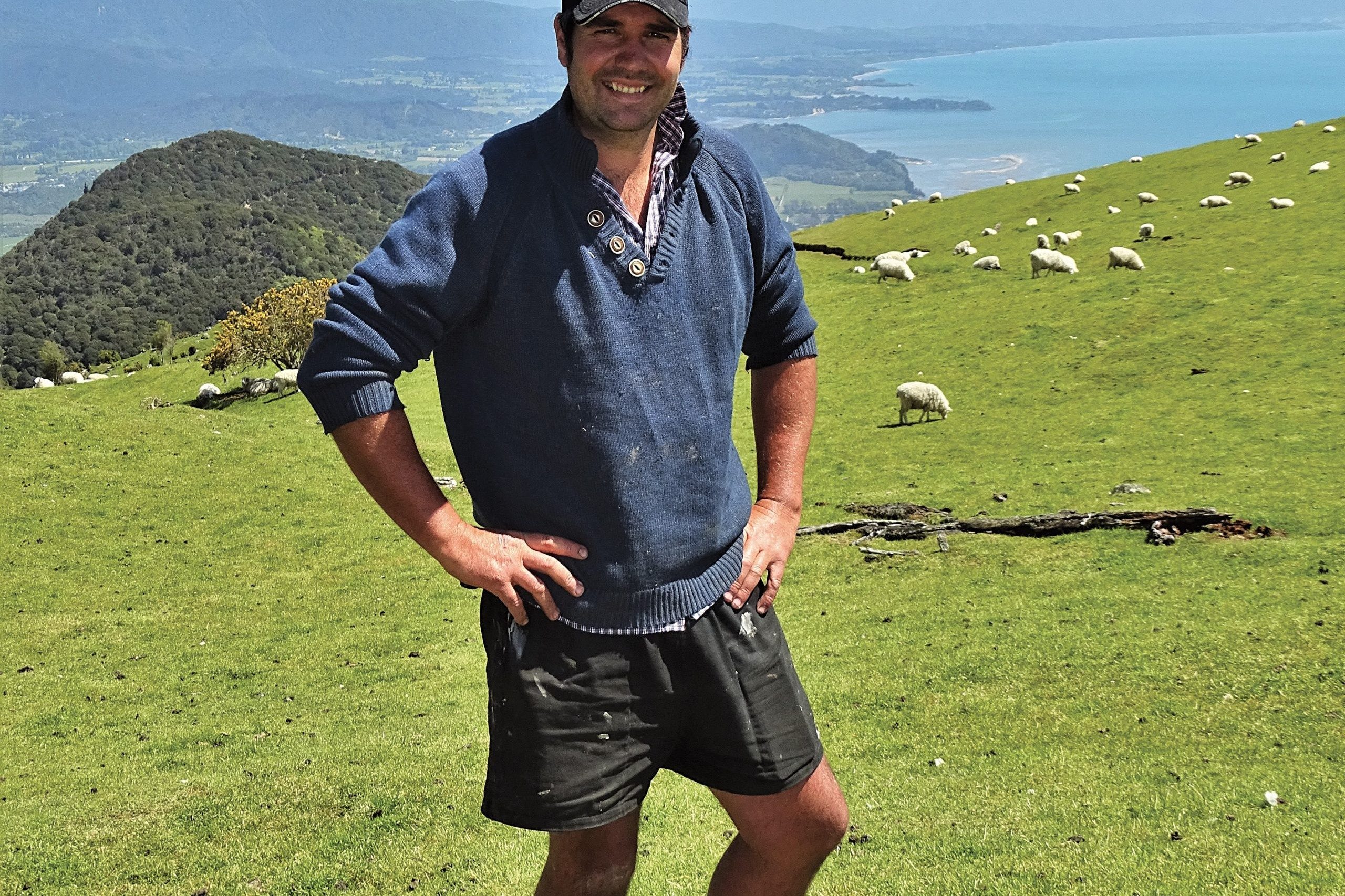

Drought alternating with extreme wet weather has prompted a Golden Bay couple to adopt a mixed pasture regime on their lease blocks. By Anne Hardie.

Drought alternating with extreme wet weather has prompted a Golden Bay couple to adopt a mixed pasture regime on their lease blocks. By Anne Hardie.

Four years ago, high numbers of triplet lambs and Italian ryegrass formed the basis for Ben Lovell and Jen Cooper’s farming operation in Golden Bay. Now they don’t flush ewes, they use teasers before putting rams out for just 12 days, and they’ve replaced ryegrass with a diverse pasture mix for their dry soils.

The couple has also expanded the business from the leased 150-hectare flat block on the south side of Takaka to include a 30ha leased block in Wainui Bay and have leased a further 300 effective hectares high up on Takaka Hill.

The first two blocks are leased from Ben’s family, based on a lease of about 22.5% of estimated turnover. The hill block is leased on a similar basis, but in their first year it was paid by investing in capital expenditure on the property, enabling them to improve aspects such as fencing. Since then, a portion of the lease is paid in cash and the remainder spent on capital expenditure. The leases for all three blocks are three-year terms with the right of renewal, with rents reviewed every three years.

It is just six years since Ben lured Jen from the United Kingdom to Golden Bay after his big OE turned into a seven-year stint that included lambing, shearing and harvesting.

Jen was an accountant and Ben spent time working on her family’s farm in England’s Peak District. At the same time the couple bought a couple of rundown houses in their local town of Macclesfield, used their DIY skills to make improvements and sold them for a profit. It made better sense than paying rent and it helped build equity.

Leasing Ben’s family farm in Golden Bay gave them the opportunity to try out ideas, and they also needed to run an intensive operation on the small farm to make it profitable. It led to high numbers of triplets and intense lambing, raising four-day-old calves and regrassing with Italian ryegrass as well as summer chicory crops to crank up production. The policy back then was to direct drill 10ha of chicory in October and then drill the Italian ryegrass into the mix in autumn.

It went well until their first hard drought hit and Ben says the ryegrass dried and died.

“It burnt right off and we became a dust bowl. We lost a massive area that year and people couldn’t offload stock, and we were buying in balage and competing with dairy farmers.”

It prompted a rethink. The ryegrass was not coping with the wet either, and Ben says during the six years they’ve now been farming in the region they’ve encountered one of the worst dry years on record and two of the wettest winters. The light stony soil is ideal through winter but cannot hold moisture through summer.

The rethink has led to a tougher mix that includes 3kg chicory per hectare, 2kg plantain, 5kg clover, 2kg cocksfoot, 3kg brome and 3kg prairie grass.

The grass is kept at a low drilling rate to keep the legume content high. Instead of two to three drillings a year, which was expensive, they now drill 10 to 15ha in September each year.

Three years after switching to the mix, the pasture is working well. Those paddocks are grazed four times through winter and the tougher grasses love the 30C summer heat. The high clover content has worked well to finish lambs and last year they finished 2100 lambs and averaged $148. That was up from 1100 lambs in 2019 without the hill block.

On the flat block, Ben and Jen lamb 900 ewes from August 20 and on the hill block they lamb another 900 ewes from September 5. Through September they also calve 45 mixed-age cows and 30 heifers on the flats, with a further 25 mixed-age cows calving on the hills.

In the past, up to 20% of their flock produced triplets and they often remove one of the triplet lambs to mother-on to ewes with fewer lambs and plenty of milk. After leasing the hill block, Ben and Jen found they couldn’t keep that pace up by themselves. They now have two small children, Sam, 4, and Ava, 1, and Jen has taken up full-time work in Takaka as a finance manager for a large local freight company. It leaves Ben single-handedly running the three blocks, including looking after the children two days a week.

To employ a full-time labour unit, Ben says they would have to increase the scale of the business considerably to make it worthwhile. Between time constraints, climate challenges and the uncertainty of offloading stock when needed, they decided they would rather do 80% of their potential production on a larger-scale operation and do it well rather than aim for 100% on a smaller operation with no wriggle room.

Now they don’t flush ewes and instead run teasers for 14 days before the rams go out on both the flat and hill blocks to ensure a tight lambing time frame, with about 90% of the ewes lambing within 10 to 14 days. They are now scanning 185% to 190% in the mixed-age ewes compared with higher than 200% when flushing. The ratio has changed to 70% twins and 7% triplets, while two-tooths scan 175% with a similar triplet rate. Survival rates end up at about 155% on the flats and 145% on the hill, even though the hill block is four to five degrees cooler than down on the flats.

“We’re doing it with more twins and fewer triplets and hardly any dries.”

Lambing in the rain

The condensed lambing makes it intense for a short period, and this year the first few days of lambing coincided with 800mm of rain pouring onto the farm in four days. On the first day of lambing they took 50 lambs off their mothers because the rain was so intense and ewes were lambing in puddles of water. Those lambs were then mothered on to ewes with singles in the days after the rain.

On the flat country with a good pasture mix, they aim to finish all the terminal lambs from Texel rams before Christmas at 18kg off mum and get them off the property. That creates room to bring the 1500 or so lambs from the hill block down to finish, with the ewes on the flat country heading to the hills for summer. Only lambs and cattle remain on the flat block and they can finish all their terminal lambs over summer, autumn and through winter by moving them every three days on a 25–30-day round. They are achieving an average of 20kg, with the last of the 2021-season lambs leaving the farm in September.

In the meantime, grass growth on the hill might not kick in until November, but it becomes good summer country for the ewes and 450 ewe hoggets. It sits high above Pohara Beach at about 500m and at the end of a narrow shingle road that passes through regenerating bush blocks with a mix of house trucks and buses and a yoga retreat.

When Ben and Jen took on the farm lease four years ago, the four-wire electric fence system was in disarray and the largely native pasture was sour on the southern slopes and not producing much. In that first year they ran low stocking numbers with the existing Perendale flock they had bought. Initially, they worked on the fences which, though dilapidated and not stock proof, had the framework to subdivide the farm well into four- and five-hectare paddocks.

“The second year we loaded it up with stock, which went wrong spectacularly. We put a lot of stock on, the feed was terrible quality and I underestimated the impact this would have on the livestock. There was no clover and the only way to chew off the old native pasture was with stock – and we did that. But probably should have done it over a couple of years.

“Now it’s a sea of clover and it has come back by itself. We had one bad year and then went forward.”

Since then, they have lifted ewe numbers from 600 on the hill block to 900, with those bearing triplets trucked down to the flat country for lambing. They happily truck stock between the three properties to make the most of the feed and climate. In winter, the hill grazes just 5su/ha, but doubles that in summer, whereas the flats graze about 25su/ha in winter and half that in summer.

Climate is a problem for subclinical facial eczema on the flat country, revealing itself too late to do anything about it. Ben says they can only do so much with zinc and pasture, and subclinical facial eczema is often a guessing game. Putting the ewes up on the hill evades the problem and there is also less of a fly problem up there.

To overcome the facial eczema on the lower, flat country, they have introduced Highlander genetics into the flock that have come through the spore counting programme. So far Ben has been impressed, with lamb weights increasing on average by 2kg.

The Perendales are slowly being phased out of the ewes and in two to three years the flock will be entirely Highlanders. Texel rams are being used as the main terminal sires over the 900 ewes on the flats, while Highlander rams are put over 600 ewes on the hill country, with Suffolk terminal sires over the remainder. Ben finds the Highlander flightier than their past Texel-Finn-Romney composite, but he likes the way the lambs “just get up, shake it off and go”.

Leading up to lambing, he has replaced the break feeding of the past with a simpler regime of putting the ewes on to a good paddock for four hours a day and then off again. The main reason for the change is the family now lives on the Wainui Bay block and it is simply easier to open the gate and chase the sheep on to a paddock of feed and then chase them out again. It avoids the risk of sheep breaking through the electric fence when no-one is there to put them back. Plus, Ben says, pushing electric fence standards into stony soils is never fun.

While Ben is enthusiastic about the sheep side of the business, he is less impressed with the cattle industry and plans to reduce numbers.

“The cattle industry is soul destroying. It’s driven by getting space at the works, with space being dictated by the dairy industry kill of bony old cows and bobby calves.”

Besides their own calves, he and Jen buy 25 to 30 rising one-year-old steers which are usually Hereford-Friesian-cross. They join their own rising one-year-olds to graze at Wainui Bay in September before heading to the works the following September.

Ben says it’s particularly hard getting cattle to the works from Golden Bay where the animals are sent to Wanganui, Feilding or Canterbury, and roads can sometimes be closed due to slips. When they need to quit cattle, they often cannot get killing space, meaning they have to carry cattle longer and it’s expensive to buy in extra feed if they are running short. On the other hand, he can secure killing space for lambs, often within a few days, at the local works two hours away in Nelson. He intends to drop cattle numbers to a bare minimum to clean up pasture and this coming autumn lift sheep numbers by up to 300 ewes.

Looking ahead, Ben and Jen want farm ownership and time will tell whether it is possible to buy the family farm. They would need to buy it at market rate and it’s in an area that competes with the dairy industry and a scarcity of productive farmland. In the meantime, they use the leases to generate income to buy property and build equity. So far, they own a commercial property in the bay and a house at Ligar Bay that they use for Airbnb. The latter has generated good income for them, even through Covid times, with Kiwis holidaying in New Zealand and prepared to pay several hundred dollars for a night’s accommodation in Golden Bay.

“We’re here to make money to buy a farm – not just to turn over cash,” Ben says.