Double trouble

The lifecycle of grass grubs may have been interrupted by this year’s wet autumn, but the delay in development may see a boom of the pest ahead. By Joanna Grigg.

The lifecycle of grass grubs may have been interrupted by this year’s wet autumn, but the delay in development may see a boom of the pest ahead. By Joanna Grigg.

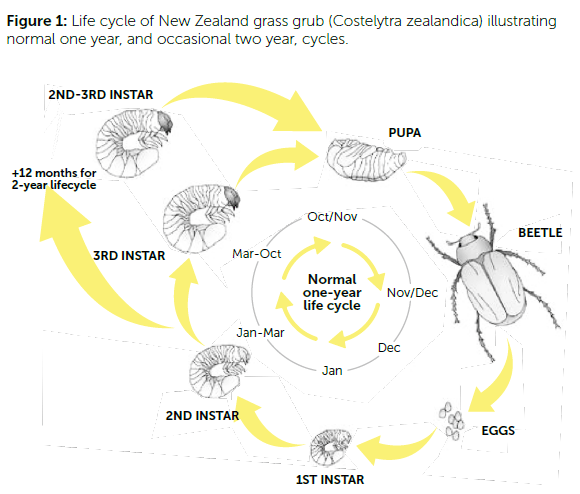

Weather conditions and increased background populations this winter may have caused a stall in the life cycle of grass grub. This means farmers may see a boomer hatch in autumn 2024, as well as the normal hatch in 2023.

This spring is the time to dig a hole to check, Foundation for Arable Research’s Dr Richard Chynoweth says.

A wet autumn saw lots of eggs hatch and grass grub feeding on pastures. But a winter food shortage may have stalled development of the grub lifecycle. This puts some of the population on hold for 12 months. “Although feeding can resume at any time,” Chynoweth says.

Food shortage can slow the development of the second or third instar larvae. They carry over in the soil into a second winter to emerge as adults the following summer. This creates a double whammy of beetles.

Farmers are best to be forewarned if considering timing of chemical control.

To check if two-year grass grub larvae are present, Chynoweth suggests farmers dig spade-sized square holes in spring. Then see if buried larvae remain unpupated (at third instar). These look like normal curled-up grubs with front legs, not big fat white pupa, that are about to emerge. They will be active (moving) if conditions are warm. If there are still third instar larvae present, then during the following spring (in 12 months) it is likely there will be a big flight of beetles.

A normal population rolling over from autumn typically has enough feed over winter to grow and mature. They erupt from the soil as bronze beetles in early summer. They lay an initial batch of eggs then fly off, feeding on trees and pasture, before laying an additional batch of eggs. Death follows soon after.

Pathogen hope for grass grub control

A pathogen that knocks grass grub population might be the long-term answer to living with grass grub.

Having a small, enduring grass grub population with sneaky ‘back-packer’ pathogens circulating within the population has the potential to keep grub numbers down. This biological control could be more sustainable than continued insecticide applications. Chemical insecticides may knock out soil organisms, including the helpful pathogens.

The clock is ticking on the ability of farmers to use insecticides such as diazinon. The use of organophosphate insecticides was reviewed by the Environmental Protection Authority in 2013, and diazinon will be delisted as a control option by 2028.

Foundation for Arable Research (FAR) scientist Dr Richard Chynoweth is feeling optimistic about grass grub pathogens becoming a workable control option. He has been researching the pathogens since 2014 and says it has potential to be applied as a bio-control agent when seeding.

“Efficacy-wise, it looks good.”

Chynoweth is part of a research team testing the potential of bacteria to protect wheat yields in the presence of grass grub. The team also includes Mark Hurst and Sarah Mansfield from AgResearch.

Trials in Canterbury have compared death rates of grubs under insecticide treatments, biological treatments (pathogens) and no treatment (control). All treatments increased the mortality and disease levels of grass grub larvae above the untreated control. Better plant survival was associated with higher yields from the treatments in four out of six trials.

“Stand alone applications via direct drilling or injection into existing pasture may also have promise,” Chynoweth says.

Like the insecticide, the pathogens were applied with the seed at drilling. The grub dies within five to 12 days after eating the bacteria. The rotting grub then becomes a host to spread the bacteria. One strain of pathogen killed as fast as insecticide. Funding for the research was from MPI Sustainable Farming Fund, FAR and Seed Industry Research Centre (SIRC).

Chynoweth says he feels science is getting closer to a robust and integrated pest management solution for grass grub.

“This would be mixing the pathogen spray on a commercial scale and applying it to seed in a cost-effective way.”

Previous research identified different pathogens that naturally occur in different regions, all of which can help keep the population in check. In the North Island (especially in Taranaki soils), protozoa and milky disease bacteria are mainly responsible for the collapse of grass grub populations. In the South Island, amber disease is the dominant pathogen. The fungal species Metarhizium sp. and Beauveria sp. have been implicated in grass grub population collapse in the Waikato region.

Drought, insecticide application and cultivation all have the potential to disrupt the natural regulation of grass grub populations by pathogens. This opens the door to large and very damaging populations of grass grub.

While commercialisation and uptake may be a year or two away, Chynoweth says farmers have some insecticide-free control alternatives. They include physical damage via trampling and heavy cultivation to grubs, when close to the surface. Pupa can be damaged by cultivation. This is hard for hill country farmers with less-intensive grazing options or who can’t get a tractor on slopes.

Trampling by stock in spring is not really that useful, unless there’s a large population of two-year larvae. Grass grubs pupate up to 20 to 30 centimetres under the soil surface and emerge during November and December in waves over a two-week period. The spread of emergence is one reason a chemical spray won’t get them all at this point.

Paddocks with high levels of grass grub in autumn will have failing plants, patches of yellowing or bare areas, and potentially large flocks of starlings or seagulls hovering over the paddock.

Plants that tolerate grass grub the best include cocksfoot and tall fescue.

“In a crop, it loves clover, and should have been called the clover grub,”Chynoweth says.

White clover in autumn is a special favourite, especially after continual crops. Annual clovers are not exempt either.

Irrigation won’t drown them. Drought can knock the population but brings other negatives.

“Pasture can handle some grass grub, so living with a lower population that gets a constant knock from biological control is probably best.”

Grass grub fun facts

- Is a native species

- Prefers legumes

- White clover a key victim in autumn

- Cocksfoot, tall fescue can tolerate larvae better

- Pathogen shown to kill grass grub and maintain wheat yield – possible bio-control

- Diazinon only available until 2028.