Shutting up some paddocks for four months could be an effective management tool for hill country farms in drier regions but timing is crucial, as Mike Bland explains.

Trial work on Jon and Fiona Sherlock’s North Waikato farm has shown encouraging results, despite two drought years in a row. Farmax modelling shows a deferred grazing programme may add as much as $36,000 to the bottom line.

The Sherlocks are now considering deferring up to 15% of their farm annually.

Otorohaea, a 575-hectare (effective) hill country farm at Waingaro, is among three farms involved with the Sustainable Farming Fund (SFF) project designed to quantify the benefits of deferred grazing on hill country sheep and beef farms.

AgResearch scientist Dr Katherine Tozer says the trial, which began in July 2017, aims to build on research conducted in New Zealand in the 1990s and in Australia over the past decade.

“From a practical point of view, deferred grazing is a useful tool to control pasture quality over the whole farm. If we take 10 to 15% of the farm out of grazing for up to three months we know we will take a hit in terms of production from these areas in the short term. But the payback could be a significant increase in ryegrass populations and drymatter production after deferring.”

Tozer says trial results show that pasture quality declines during the deferred period but improves again after deferring. While deferred pastures could not be grazed in summer, pasture drymatter production on treated areas was higher from autumn onwards.

“Overall, there is no net change in pasture production in the deferred paddocks. The regrowth the year after deferring compensates for the loss of production during the deferred period.”

Sherlock admits he was initially sceptical about the benefits of deferred grazing on Otorohaea, which is in a traditionally summer-dry region. Otorohaea has about 50ha of rolling ash contour and the rest is medium to steep hill, most of it Class 6/7.

Sherlock says the results of ‘unplanned’ deferred grazing on his farm fuelled this scepticism.

“Sometimes pastures get away on you, so you shut them up late and then use them for autumn grazing for cattle. But these pastures are always slow to grow back in winter and the benefits in terms of drymatter production and pasture quality are negligible.”

Sherlock says the trial gave him the opportunity to measure the benefits of a planned deferred grazing programme.

Funded by SFF, Beef + Lamb NZ, Ballance Agri-Nutrients and BoP Regional Council, the trial involves comparing the effects of conventional rotational grazing with two deferred grazing regimes – an early-opening treatment that is locked up for about six weeks allowing sufficient time for the ryegrass to flower, and a late-opening treatment that is locked up until seed set or seed fall. This takes about three months.

About 6ha of Otorohaea was shut up in the 2018-19 season. A 1ha block was split into 12 smaller trial plots, with additional paddock-scale trials conducted on both rolling-medium contour and steep hill on a north-facing sidling.

Paddocks were closed in October, with the early-opening treatments grazed in mid-December and the late-opening areas grazed from February 20.

Sherlock thought the trial might fail because dry conditions meant there was very little feed in the deferred area.

“But a few months later you could definitely see the difference between the deferred and non-deferred paddocks.”

In the first year after grazing, deferred paddocks grew significantly more pasture drymatter (DM) than untreated areas. Prior to their first grazing, deferred treatments had more than 4000kg DM/ha of pasture, compared with about 2500kg DM/ha on non-deferred areas. This advantage gradually reduced, and by June 2020 there was minimal difference in pasture production between deferred and non-deferred areas.

At the end of the deferred period, deferred pastures were grazed down to 1300-1400kg DM/ha to allow light through to seedlings and new ryegrass tillers on the existing plants.

Sherlock says deferred paddocks were grazed with R2 heifers because sheep would have struggled with the longer feed. Mixed-age ewes were used for the clean-up.

He says the timing of grazing is crucial.

“You’ve got to graze in Feb/March to give it time to recover for winter. The idea is to treat it like a new grass by grazing lightly at first, then easing it back into the rotation.”

Tozer says in a summer-dry situation, deferred grazing provides the ryegrass population with an opportunity to rebuild.

“Deferring shuts up a big wedge of feed that sits there over summer and creates this big seedbank for the future. In a dry year pasture growth will slow right down but the regrowth in autumn is phenomenal.”

Ryegrass tiller counts taken in June, when the drought had ended, showed the deferred trial plots had a tiller population of 6800 tillers/square metre, compared with 4500 tillers/square metre in non-deferred plots.

Tozer says it’s crucial to take the pressure off ryegrass to enable the flower to set seed. Paddocks should be cleaned up in time for autumn rain.

Sherlock likes the idea of shutting up to 15% of Otorohaea annually and rotating deferred grazing around the farm to rejuvenate pastures. He plans to run his own informal trial on some larger paddocks, totalling about 20-30ha.

“For us, deferred grazing will be season-dependent. If feed’s tight, we won’t shut up,” he says.

“But we’ve got nothing to lose if conditions are good, and we will shut up paddocks in October and increase stocking rate in other paddocks to maintain pasture quality.”

Sherlock says he will review the feed situation in November/December and “if we are not under the pump feed-wise” he will keep deferred paddocks closed up.

He says the potential also exists to integrate a deferred grazing programme with the aerial sowing of legumes into pasture.

Tozer says one of the biggest advantages of a deferred grazing programme is that it helps maintain pasture quality on non-deferred areas.

The other farmers involved in the trial are Allen Coster and Rick Burke from the Bay of Plenty. Sherlock, Coster and Burke are all members of Beef + Lamb NZ’s farmer council.

Coster says deferred grazing is a cost-effective way of maintaining pasture quality, (Country-Wide Crop and Forage, September 2019).

He says the deferred treatment areas on his Kaimai farm grew more drymatter through winter and looked visually better.

Measurements taken in October 2018 showed the late-opening treatments had a tiller density of 4700/square metre, compared with 2700 tillers/square metre on the conventionally grazed treatment.

In spring 2018 the grazed treatment produced 3400kg DM/ha, with the deferred treatment growing 4260kg DM/ha. However, by summer 2018/19 drymatter production was similar on both treatments.

Nutrient and water retention

There was less bare ground in the deferred treatment areas, and a glasshouse trial showed a big increase in the root mass of simulated deferred grazing treatments. Deferred treatments had more than double the root mass of the conventionally grazed treatments, with a significantly higher proportion of roots at a depth of 0.65-1.0 metre in the glasshouse study.

Tozer says the implications for nutrient and sediment run-off, moisture retention and water quality could be quite significant.

“Deferred grazing might be an effective environmental mitigation tool, but we need robust science to investigate this.”

Coster grazed the treatment blocks with dairy heifers and they achieved similar weight gains as they would on the conventionally grazed pasture.

But he says breeding cows or cull dairy cows would be more appropriate classes of stock for grazing deferred areas because weight gain is less of a priority.

Tozer says farmers wanting to use deferred grazing as a tool should take a long-term approach.

“You’ve got to have enough feed in the system to be able to drop paddocks out, and you need the right class of stock to graze deferred pastures.”

Timing is crucial. To be effective, pastures should be locked up before they flower and set seed and not opened for grazing until after seed has dropped.

“That will enable you to capture the benefits of new plants produced by the ryegrass seedbank while allowing the existing plants to grow more tillers. The danger of shutting up for too short a period is that you will lose some of the benefits for the herbage and the soil. It’s important to consider what is happening below ground as well as above it.”

And locking up a paddock full of weeds in the hope of suppressing weed growth is pointless.

“If you lock weeds up, you’ll only end up with more weeds.”

Tozer says the value of deferred grazing will vary from farm to farm and season to season.

In situations where summer rainfall is adequate, such as on Coster’s farm, deferred grazing will help ryegrass grow more vigorously and produce more tillers.

“In a really dry year the extra feed produced by deferred grazing could be critical and the seedbank will be an important source of new ryegrass plants. In a wetter year, the growth of existing plants will boost the ryegrass tiller (stem) population.”

The trial finished in August 2020.

Better pasture boosts bottom line

Farmax modelling by AgFirst consultant Steven Howarth shows the major driver of a positive return from deferred grazing is the impact on non-deferred areas.

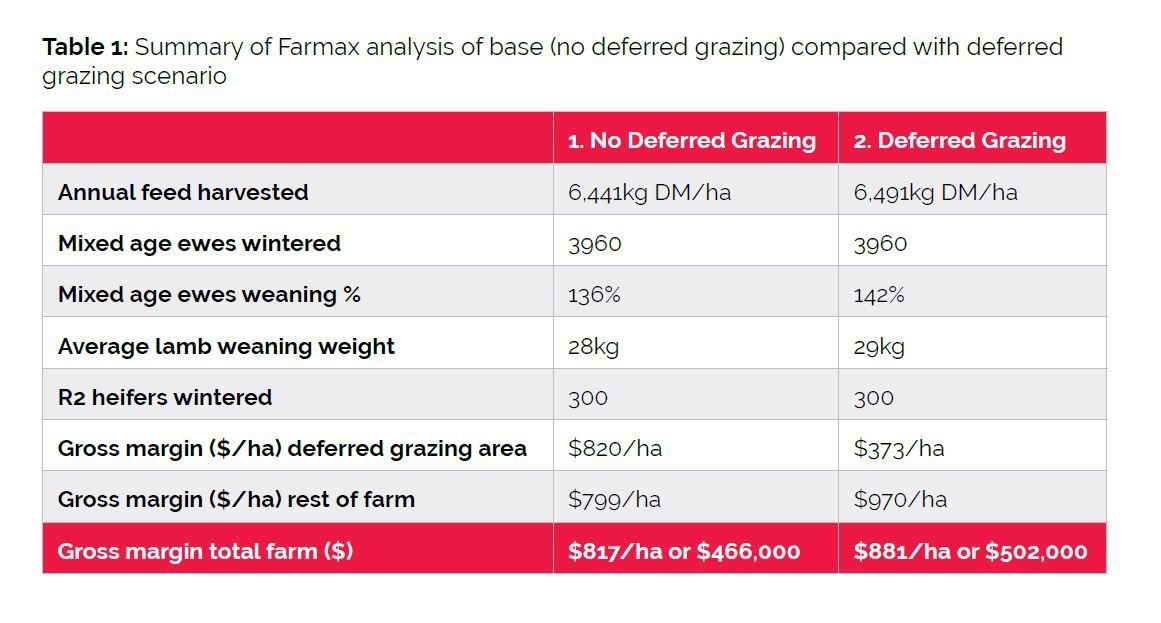

He says deferred grazing on Otorohaea enabled grazing pressure to be increased over the rest of the farm, reducing peak spring pasture cover by about 175kg/ ha, with an associated increase in pasture quality. This leads to improvements in per head stock performance, lifting profitability by up to $36,000 (see Table 1).

His analysis uses historical herbage and livestock performance data from Otorohaea and data collected during the trial. Modelling is based on a ‘typical’ year.

It assumes the decision to defer is made in October, with the size of the area dependent on pasture growth at the time. If feed levels are low, deferred grazing may not be an option. “Conversely, if the surplus is large the area deferred may need to increase.”

Scenario one in the analysis represents a typical year with no deferred grazing. The second scenario applies a deferred grazing regime and assumes a 10-25% increase in pasture growth on deferred areas over the following year and an increase in pasture quality over the rest of the farm of 0.2 megajoules (MJ) of metabolisable energy (ME), averaged over 12 months.

Howarth says the results show that an increase in pasture growth following deferred grazing is required to offset the pasture losses over the deferral period.

He says the decision to defer is made without knowing what conditions will be like in summer.

“The flow-on benefits of having a deferred area in a drought may be greater than in an average year because it provides more feed in a time of deficit. Drought recovery is also important, and it was observed that for Otorohaea the deferred area grew 25% more grass compared with other areas.”

Deferred grazing may also suppress Californian thistles and reduce exposure to facial eczema spores.

Howarth says deferred grazing should be regarded as “an option in the toolbox for farmers”, especially if they have a large spring surplus to control.