Decision time for farmers

Farmers need to tune in fast to pricing proposals for agricultural emissions, writes Joanna Grigg.

Farmers need to tune in fast to pricing proposals for agricultural emissions, writes Joanna Grigg.

Suddenly it is the most important issue, leaving freshwater strategy, biodiversity strategy and pastoral lease reform in its wake.

February is the month for attending a roadshow and putting in a submission.

Carbon dioxide, methane and nitrous oxide are the greenhouse gas outputs from stock and fertiliser that look to be ‘taxed’ in some shape or form. The plan is for a pricing system for farms to be designed, tested and up-and-running within three years.

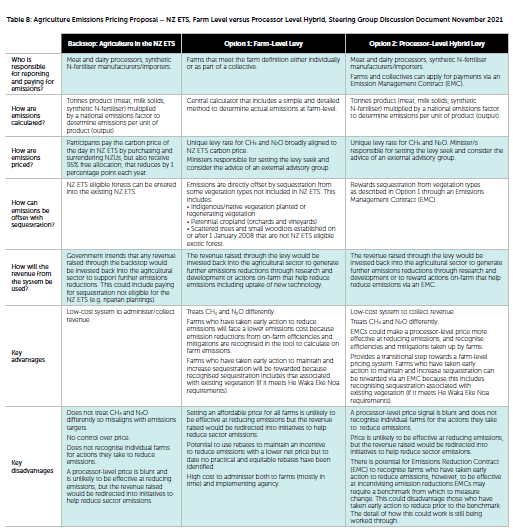

Whether gases are measured and levied at the farm-level or at the processor level (as meat or milk comes in) is what will be discussed at the roadshows. These are hosted jointly by Beef + Lamb NZ and Dairy NZ, and supported by Federated Farmers, although feed into the wider primary industry consultation (known as the Primary Sector Climate Action Partnership or He Waka Eke Noa).

Warwick Lissaman, a breeding/trading sheep and beef farmer from Marlborough, is keen to get an answer at the roadshow as to why farmers should buy-into paying a levy, as well as the options for how.

As a previous NZ Grassland Association president, Marlborough Research Centre board member, Chilean Needle Grass Action Group chair, host of dryland legume research and most recently, the Beef + Lamb NZ Northern South Island rep, Warwick has shown to be up-to-speed on the science, markets and politics shaping agriculture.

He says farmers are good at following market signals and will take ownership of an idea if they understand the reasoning behind it.

“I do want to know if the agricultural emissions pricing scheme is going to be a good end-game for our markets, will it improve the environment on the farm or is it a platform for the Prime Minister to stand up and say New Zealand is great?

“Show me the actual difference it will make to the market big picture, then I will make the changes needed.

“I understand farmers must play our part whether we agree with it all or not.

“When farmers get the reasons, they are more likely to buy in. The ‘why’ will drive the data needed and the reporting to be as efficient as possible.”

He queries whether a better option entirely would be for farmers to formally measure their emissions for market advantage but not be levied on them.

“Would education and the use of reduction tools make the environmental difference we need, rather than a scheme tax?

“I’ve made environmental changes on my farm to make my products more appealing, but without a tax to drive change.”

He acknowledges farmers collectively are faced with designing a system and backing it by the end of February, or the Government reserves the right to price agricultural emissions in the NZ Emissions Trading Scheme (ETS) earlier than 2025.

In December he challenged his farming peers to watch the 2021 Hopkins lecture by Dr Rod Carr (the Chair of the Climate Commission) on YouTube – to understand what is driving him.

“It was interesting to hear that total emissions linked to producing a kilo of beef or lamb is about double that of pork and chicken, although off a different landscape.

“Carr’s comment to stop listening to your own bullshit was confrontational, but I agree farmers do need to look globally and be in step with wider views.”

Lissaman is not ready to pick between the proposed farm-level or processor levy options as he wants more information.

“Can landowners move between the options?

“Whatever one I vote for, it has to be simple – with figures dropping down from our annual accounts and easy-to-use mapping tools.

“Farmers are very busy people who can’t keep being loaded up with more stuff or costs.”

After running his farm stock numbers, fertiliser and shrub/tree areas through the GHG Calculator (Beef + Lamb NZ version) he says his number is really variable over the years. As the 400ha farm, Breach Oak, runs between 2500 to 4000 stock units, with a large trading volume, plus ‘lumpy’ fertiliser purchases, he would prefer to see a rolling three-year average figure used.

He has been planting woodlots as part of the wider farm plan and is using an environmental consultant to plan which land to retire and what to farm. His pick is that at least 10% of his land will need to be on a rotation for, as he puts it, “non-ruminant food producing” but he is unsure whether more land needs to be added over time.

Greenhouse gas emissions figures and a plan for reduction are likely to be part of my Farm Environment Plan, he says.

Across the industry, he sees the age of farmers, debt levels, and land scale will drive the amount retired into trees.

“We don’t want our landscape covered in trees as there will be much less water making it downstream – what will that do to the viticulture-based economy in Marlborough for example?”

Lissaman says any pricing scheme should have an incentive to allow turnover of stock quickly, to calculate actual days alive on the farm. It should also reward farmers who both off-set emissions and can produce the same product for less emissions.

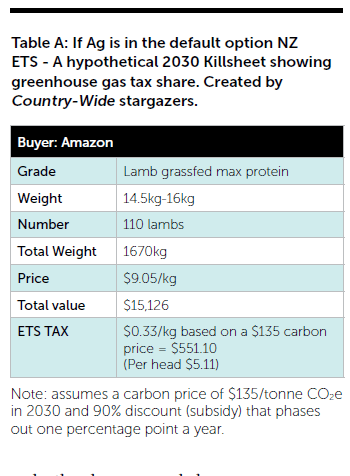

One negative of the default NZ ETS is that it has a set tax per stock unit so does not reflect farm systems that are able to produce less emissions per kilogram of product. There would not be the commercial drive for better breed, genetics, or feed systems. Another negative is that most farm shrubland, shelter belts and pre-1990 bush does not qualify as off-sets in the ETS.

- Watch: Hopkins Lecture Dr Rod Carr www.youtube.com/watch?v=d_4Gj05FTNk