Dan, Dan the Ovis man

After nearly 30 years dedicated to education and awareness around Ovis (sheep measles), Dan Lynch is hanging up his boots. He spoke to Rebecca Greaves and reflected on the highlights, achievements and the challenges that remain. Photos: Brad Hanson.

After nearly 30 years dedicated to education and awareness around Ovis (sheep measles), Dan Lynch is hanging up his boots. He spoke to Rebecca Greaves and reflected on the highlights, achievements and the challenges that remain. Photos: Brad Hanson.

Working with both the meat industry and farmers to combat sheep measles has been a blast for Ovis Management project manager, Dan Lynch.

Involved since its inception, he has spearheaded the Ovis Management approach to educating and raising awareness about this disease – there are not many roads in rural New Zealand he hasn’t driven up on his quest to quell Ovis.

Ovis Management is a non-profit organisation promoting the control of sheep measles. It is owned by the Meat Industry Association of NZ(MIA) and funded by meat processors.

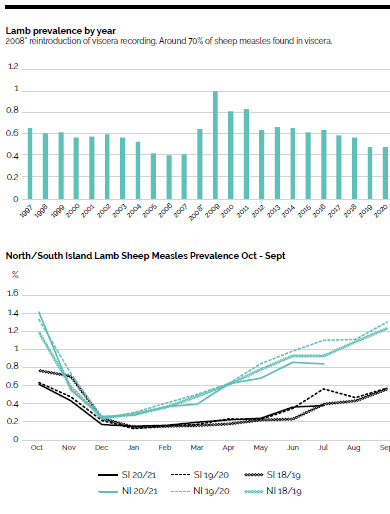

The proof is in the pudding, with NZ having low levels of sheep measles. The rates in sheep and lambs decreased by 66% between 1994 and 2018, largely due to effective dosing of dogs, which carry the tapeworm that causes Ovis. Despite these low levels, there is still a seasonal prevalence of sheep measles, and an outbreak can cause a lot of damage in otherwise healthy stock – and significantly impact a farmer’s bottom line.

The on-going challenge is around trade stock and complacency and, with such low levels of Ovis, ensuring farmers remain vigilant and take steps to minimise the risk of an outbreak.

Dan has a background as a meat inspector in both New Zealand and Australia and came on board with Ovis Management when it was set up in 1992. “One of the things that intrigued and frustrated a lot of people at the time was the amount of Ovis going on in plants, and in 1992 sheep measles exploded.”

We might take our Ovis status for granted now, but back then, sheep measles was on the cusp of becoming a serious issue for NZ. Container loads of meat had been rejected into Canada and the United States, due to Ovis, and it had the potential to become a major problem, as the market had become sensitised, Dan says. The industry knew something needed to be done, and fast.

As part of his job as an inspector Dan had spent time working with MAF (now the Ministry for Primary Industries) on farmer feedback programmes. He was instrumental in setting up the Ovis Management programme and became the project manager, a role he expected to hold for two or three years. Little did he know it would become an all-consuming job for 29 years, a job he has excelled at.

When Ovis Management started out it was the first to explore developing a pest management strategy, and it looked at developing a strategy, similar to NAIT. With an estimated cost of 30-50 cents per lamb processed, this was quickly vetoed.

A path of education and awareness

Establishment coincided with finance minister Ruth Richardson’s ‘mother of all budgets’ in 1991, which included the disestablishment of the Hydatids Council. The Hydatids Council had previously been tasked with dealing with Ovis.

“The thought was that sheep measles was a meat industry problem, and it was up to them to deal with it. Hence, the industry started looking at a programme, but they didn’t want it to cost farmers millions of dollars for something that was essentially a market risk.”

Instead, it was decided Ovis Management would go down a path of education and awareness. A key factor was the development of a central database that all meat companies were prepared to provide supplier kill data into, in order to track farmers with sheep measles.

“This was a lower cost option but it did take some convincing to get meat companies to hand over their supplier data. We demonstrated that we would hold it and respect the farmers’ data. I had planned to come to the North Island for two or three years, but once we got started, and the opportunity to build the database from scratch, it became all encompassing.”

Since its development, the database has evolved and now also works with the deer industry to track Johne’s disease.

“The critical thing is it (the database) is owned by the industry, and the farmer’s data remains the farmer’s data,” Dan explains.

Much of his focus has been on collecting data, and ensuring that it is as accurate as possible, which has been an ongoing challenge with 33 different plants providing data. The other major part of his role has been education and awareness, visiting farmers throughout the country. As well, Dan has been tasked with visiting 200 vet clinics, providing them with resources.

A job done well is evidenced by the fact NZ now has an extremely low prevalence of sheep measles. But that means it’s now something that’s not at the forefront of farmers’ minds, and that in itself is a risk.

“Farmers do take it for granted. Ovis Management has moved to more of an educational role now. On the whole, farmers have been amazing. The overwhelming majority of farmers are prepared to spend money on dosing their dogs, on something that’s not visible.”

Dan puts a lot of the success of the programme down to increased dog dosing. He also points to changing land use having an impact. The spread of dairying and reduction in sheep farms means there are simply fewer sheep around now, which has helped enormously.

Reflecting on his time with Ovis Management, Dan says he is most proud of getting the meat companies to trust the company with their data, ditto for farmers being so responsive to the message.

“It’s been fantastic. I’d hate to think how many farm yards or kitchens I have sat down in and had a yarn about Ovis. Getting to meet so many people has been great, I enjoy people. Over my time we have also had great, supportive boards. I’ve only had two chairmen – Roger Barton and Geoff Neilson – both understanding and committed farmers. Bruce Simpson, an epidemiologist who we have worked with over all this time, has also been key in providing direction and support.

“The experience has been so enjoyable, meeting so many good people both within the meat industry and across the farming industry.”

In his retirement Dan and his wife Sue had hoped to travel overseas, as all their children and grandchildren live abroad, but Covid-19 has put a spanner in the works.

“We want to spend a significant length of time with them, but Covid is a proper pain. Touring New Zealand doesn’t hold much interest as I’ve been all over our country with work. I’m involved with harness racing and the local club, so I’ll continue that involvement.”

Dan’s successor at Ovis Management, Michelle Simpson, has been appointed and Dan says he is delighted about his replacement.

“From what I’ve seen of her, I’ve been very impressed.”

When it comes to managing Ovis in the future, while we might be on the right track, there remain road blocks. One area that needs further work is around store farmers and trade lambs.

“Potentially we are telling you, you have a problem, but if you are buying in lambs from someone else, they don’t know they have a problem.”

Steps from here will be incremental, Dan says. The Farm Assurance Programme (NZFAP) now requiring monthly dog dosing is a step in the right direction.

“Increasing the rate of dosing on farms that sell trade lambs is key. If you are not killing lambs through the works, no data is captured on your farm. With a lot of trade lambs, the origin disappears when they are killed.”

Where to next will be a decision for the industry, he says. EID would help, but he acknowledges there would have to be other benefits for farmers, other than Ovis management, to make it a viable proposition.

“The objective hasn’t been eradication, it was education and awareness. We’re in a really good place now, it’s just a case of sustaining and hopefully building on what has been done.”

Ovis project manager appointed

With a background in science, and more than 20 years of experience in the animal health industry, Michelle Simpson is well placed to pick up where Dan leaves off when it comes to Ovis management.

Based in the Rangitikei, Michelle has spent the last 10 years working for a privately owned vet practice in Bulls. She has previously worked at vet path labs as well as spending time on the road selling for Donaghys. The role with Ovis Management felt like a good fit for Michelle, who understands the importance of disease prevention.

“Sheep and beef is my passion and this is an opportunity to go back to sheep and beef, and get back out in the field, meeting people and spending time outdoors.”

Michelle says she has a huge amount of respect for Dan and what he has achieved with Ovis education and awareness. “I feel he’s handing over the torch. He’s done the hard yards to get it to where it is now and I’m feeling privileged to have this role, as it means so much to him.”

Initially, she says her focus will be to carry on where he leaves off. “I do intend to make the role my own, but respectfully. I won’t be moving too quickly, but to see where I can contribute, over time.”

Why should farmers care?

Export markets: “New Zealand farmers are extremely proud of the product they produce. Dare I say it, the strength of our marketing is on our clean, green image. Exporting meat with little pusy cysts is not seen as a desirable outcome.”

Financial impact: “Farmers who get hit with an Ovis storm can get lambs condemned. A few years ago I had a single farm with lost earnings of $30,000 from animals being condemned. Each year a small number of farms suffer substantial financial loss, and these are good farms, but something went wrong.”

WHAT CAUSES OVIS?

Sheep measles is caused by the Taenia tapeworm, which can be carried by dogs. The tapeworm produces eggs, which are transferred to pasture in dogs’ faeces and then ingested by sheep. The eggs can survive for many months and be spread over large areas (up to 10km, covering 30,000 hectares) by wind and flies. After ingestion, the eggs penetrate the sheep’s intestinal tract, are moved around in the blood and form cysts in muscle tissues.

Dogs that eat raw or untreated meat or offal containing live ovis cysts develop intestinal tapeworms, which develop to maturity in about 35 days. Some dogs carry three to four worms and each worm will produce up to 250,000 eggs a day. These are then deposited in pastures and the cycle continues.

HOW CAN FARMERS MINIMISE OVIS RISK?

- Make sure your dogs are in a regular monthly dosing programme. That means all dogs on the farm, including pets and pig dogs. The highest risk dogs on the farm are usually the pet jack russell, foxy or lab.

- Get your partner involved. “That tends to be more effective, I don’t know why. If your partner is on board, it makes a difference.”

- Restrict external dogs coming on the farm. “Often I hear of the shearers turning up with a dog, and that dog may not have been dosed.”