Andrew Swallow

Keep paddocks growing something between harvest of one main crop and sowing of the next to reap many benefits, growers gathered for FAR’s main summer field day, Arable Research In Action (ARIA) heard.

Often referred to as cover crops, such interim sowings may also be dubbed catch crops, service crops, or green manures, FAR’s Alister Holmes explained.

However, it doesn’t really matter what you call them: the common theme is they all provide one or more benefits. For example, capturing nutrients which would otherwise be leached, enhancing soil structure, suppressing weeds, reducing reliance on pesticides especially herbicides, or, as in the case of legumes, fixing nitrogen which a following crop might use.

“You’ll hear a whole heap of terms for them… and I’m not sure there’s a very clear difference between them, or that it really matters,” Holmes commented at Aria. “Any cover crop grown will provide multiple services.”

While much has been written and published on the capture of nutrients by cover crops, notably as part of the Dairy NZ-led Forages for Reduced Nitrate Leaching programme, the focus of the ARIA presentation was on weed suppression and reduced reliance on herbicides.

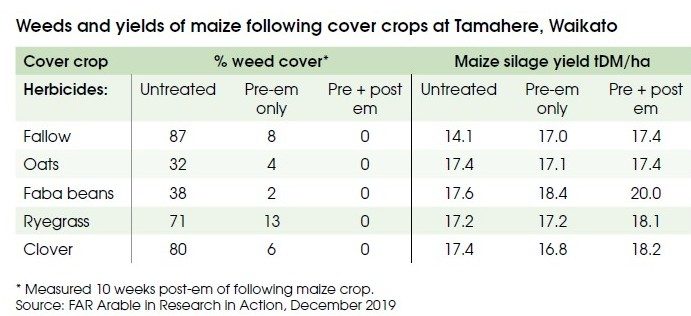

FAR’s trials at Tamahere, Waikato, with oats, faba beans, annual ryegrass, or clover compared to fallow after maize maincrops are now in their fourth season. Holmes presented results from 2018 when oats and faba beans provided significantly higher weed suppression (see table), and all covers enhanced yield of the following maize compared to fallow where no herbicide was applied. Holmes also noted yields of maize untreated by herbicide following the cover crop were on par with herbicide treated.

“We’re finding we can get away with just a pre-emergence or one post-emergence.”

AgResearch’s Trevor James, a co-presenter at ARIA, noted reduced weed competition gave growers more flexibility in when and which herbicides they used, and meant there was less pressure to apply a herbicide in less than ideal conditions, such as when it’s windy or too dry, which in turn reduced the risk of weed escapes and herbicide resistance build up.

As for which is the best cover crop, Holmes said there’s no simple answer as it all depends on what you are trying to achieve and timing of sowing and destruction, however some general principles apply: cereals establish quickly and are good at mopping up residual nitrogen; legumes are best for fixing nitrogen for release to following crops; deep tap-root plants help improve soil structure.

“It’s not simply a matter of saying this is the best cover crop for this region.”

James noted different covers may be needed one year to the next, despite being in the same rotational position, due to differences in soil moisture and timing. He encouraged growers to do their own trials, ideally with half paddock comparisons. “There’s nothing like every grower doing a bit themselves to help develop the science faster….

“Cover crops are difficult to use, there are a lot of challenges, but there are also a lot of rewards,” he added.

While FAR’s research to date has focused on single species cover crops, Holmes noted the potential for mixed species covers to work too, with each species providing different, complementary benefits and improving the crop’s ability to succeed in a range of seasons and situations.

DON’T GET GREEDY

Holmes cautioned against building the drymatter a cover crop could provide into feed or financial budgets. Once in those budgets, typically it would be harvested, either by machine or grazing, even if conditions weren’t favourable, damaging soil structure and compromising the following main crop.