BVD can be managed in herds

A level of complacency sees a serious cattle disease continue to cause problems for cattle, writes vet Andrew Cochrane.

A level of complacency sees a serious cattle disease continue to cause problems for cattle, writes vet Andrew Cochrane.

As rural vets we are constantly involved in BVD breakdowns and the ensuing damage this causes to beef productivity and profitability.

Every year at our practice in Northern Southland, we find ourselves having the discussion with farmers following a poor scanning or routine blood testing and the past season has been no exception.

It’s not through lack of education, BVD (bovine viral diarrhoea) has been a relatively constant topic for the last decade, whether through the rural press, veterinary newsletters or farmer seminars/field days. But unfortunately there still seems to be a complacency among farmers and livestock agents, that sees this easy-to-manage disease continue to cause problems.

As part of the mycoplasma bovis eradication effort we have blood tested a lot of beef cattle recently and this has been a great opportunity to screen for BVD at a heavily discounted rate. Many of our farmers took us up on this offer and it has been a useful way of identifying herds with underlying BVD issues. Any beef farmers reading this that haven’t yet taken this opportunity, I highly recommend talking to your local vet clinic about getting your herd tested under this offer.

Of the herds tested we found 21% with active BVD infections, lower than the national average of 45-55%, but significant nonetheless. Some of the worst-affected had been impacted by poor scanning results with one farm only scanning 50% in-calf.

The best thing about BVD is that once you commit to eradicating it, this can be achieved relatively quickly through a test and cull policy. Good biosecurity measures can then be enough to keep BVD out for good and when this isn’t possible an effective vaccine is available to protect your herd.

There will most likely be a national eradication scheme in New Zealand within the next decade, but why wait when you could easily eradicate BVD from your property now? Need more convincing on the merits of eradicating BVD? Let’s look at what happens when it all goes wrong…

One of the affected farms we dealt with last year is an example of the impact it had and some of the tough decisions that had to be made during the outbreak.

We were first alerted to this farm in March following a disappointing pregnancy scanning. Initial blood work showed high exposure to BVD (S/P ratio of 1.63). Follow-up testing found 30 of 663 animals were positive for BVD and likely to be persistently infected (PIs). These PI animals were culled and by calving time the cattle on the farm were BVD-free. However, we knew there remained a risk of BVD infection in the calves yet to be born.

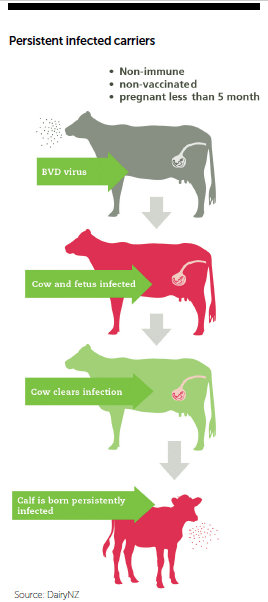

This is the ‘Trojan cow’ scenario, where a pregnant cow that has tested negative to BVD gives birth to a positive persistently infected calf. If these calves are left in the herd during the subsequent mating there is a real risk of further BVD infection and productivity losses.

Testing calves at foot can be a logistical nightmare, especially in this case where a late calving spread meant cows were still calving late into spring. In the end, 456 calves were tested in mid-December and 95 (21%) came back positive!

This was a shock for all involved and it took several conversations and emails to plan the next step. With the start of mating already delayed and Christmas fast approaching some tough decisions had to be made quickly. Fortunately, we had already decided to vaccinate the herd prior to mating which would help provide some protection to the cows. Regardless, experience with past outbreaks told us that some bold actions were still required and we had four basic options:

- Cut our losses and cull all the positive calves, continue with mating as planned

- Draft out the positive calves, match them to their mothers and mate this group separately

- Early weaning – wean the positive calves, hope for the best and mate the cows as planned

- Do nothing, rely on the vaccine to provide protection.

Option 1 was the tidiest option but not a pleasant one. This would also see many transiently infected calves being culled unnecessarily.

Option 2 was the preferred option but we had tried this approach before (albeit on a much smaller scale) and had issues with bull fertility. The result was an 80% empty rate due to the high transmission of virus overcoming the vaccine and rendering the bull infertile.

Option 3 wasn’t really suitable as some of the calves were only a few weeks old.

Option 4 was still risky, especially given the high amount of BVD virus circulating.

In the end the farmer chose a mixture of the options. Some calves were weaned very early and as expected many of these subsequently deteriorated, requiring euthanasia as a result of stress and progression of the disease.

A group of the remaining 65 positive calves and their mothers were kept in a separate mob and left unmated initially. This group of calves was retested a month later, the calves confirmed as PIs were then weaned (at a much better age) and the bull was joined with the cows and negative calves.

In total 30 calves tested negative on their second test and were therefore found to have been transiently infected. These were able to continue in the herd with no long-term ill effects and while mating had been delayed five weeks for 65 cows, this was deemed better than risking a 80% dry rate.

A decision about what to do with the weaned, positive calves remains. These calves are a high risk to the herd and keeping them on the farm is not generally advisable. On top of this, many of them never make it to an age or condition where they can be finished.

One option considered was to send them to slaughter at weaning, where they are killed as a ‘cull cow’ and can still fetch up to $400. However, in this instance a decision was made to send the calves to a separate block with no breeding cattle. What happens to them from here is still up for debate but one possibility is that another farmer takes them on and attempts to finish them, fully aware of the risks. This farmer doesn’t have any breeding cattle and the arrangement is such that he wouldn’t pay for cattle that don’t make it to finishing.

While some of the solutions to this outbreak were unusual, the outbreak itself is similar to many that happen around the country every year.

The outcomes often have a significant financial and emotional impact, leaving the farmer with lost production and replacement animals to source. Fortunately, the full force of these impacts can be avoided with a robust BVD management plan. Talk to your local vet about how you can control the threat of BVD in your herd.

- Andrew Cochrane is a vet with Northern Southland Vets.

Four options for a farmer

- Cut the losses and cull all the positive calves, continue with mating as planned

- Draft out the positive calves, match them to their mothers and mate this group separately

- Early weaning – wean the positive calves, hope for the best and mate the cows as planned

- Do nothing, rely on the vaccine to provide protection.