Farmers would be better off if they pick an He Waka Eke Noa emissions pricing option according to Beef + Lamb NZ chief executive Sam McIvor.

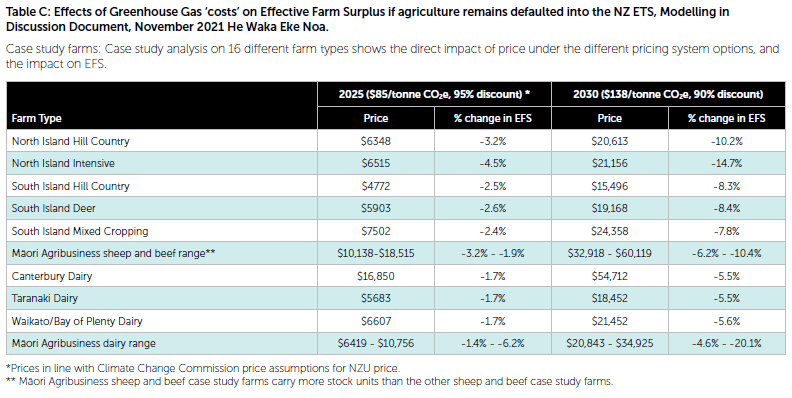

Case study analysis of 16 different farm types was done in November by He Waka showing expected changes in effective farm surplus (EFS) with an emission ‘tax’ in place via the NZ ETS.

The conclusion was, at this price and proportion, the bottom-line effect is such that it would “impact the viability of some red meat farming systems”. North Island intensive EFS was modelled to drop the most by 2030 (by 14%) while North Island Hill was down 10%. South Island Hill EFS looked to be impacted by 8% while South Island deer EFS was down 8.4%. Annually this was about $20,000. Dairy farm surplus was projected to be down 5%.

But despite the cost, the change in actual greenhouse gas emissions from agriculture is expected to be down less than one percent than 2017 levels. This point needs to be front and centre.

In the ETS farmers would not have a way to be rewarded for change, or for most farm vegetation offsets but would get stung at a projected 33c/kg sheep meat, 20c/kg beef and 43c/kg venison by 2030. Fertiliser ‘tax’ is expected to be 7c/kg N at this point in time and increasing each year. Carbon price is expected to be about $138/tonne in 2030 but, most importantly, only 10% of the true cost would be allocated on to farmers (90% subsidy rate). This subsidy drops one percent each year. If the full market carbon equivalent costs were charged, most farms would be out of business – no question.

He Waka have come up with bespoke pricing schemes that are both carrot and stick. They have rewards for farmers for reducing greenhouse gases and importantly, a price cap to keep them cheaper than the ETS about 4-5% reduction by 2030. Under the ETS option, agriculture is unlikely to see reductions of one percent. This is the point of the whole exercise.

McIvor predicted the cost to farmers is hard to pin down although they are working on it. Modelling the farm surplus under the alternative options (farm-levy or processor) is a hugely complex task.

He said the cost to a farm depends on many unknowns such as market price, adoption rate of methane reduction tools by farmers and sequestration rates.

“Models are a useful guide but we have to be careful relying on them to drive decision making.

“It’s an ongoing process as we lead up to the consultation phase.”

Both the farm and processor options look to have a levy rate for methane and nitrous oxide broadly aligned to NZ ETS carbon price. As to the actual price of the levy, He Waka states “Ministers responsible for setting the levy seek and consider the advice of an external advisory group”. Looking more closely under the bonnet and giving each scheme a test drive is the only way that the true cost and mechanisms will be revealed.

McIvor said sheep and beef farms are less efficient at converting feed to product than dairy. This means they are more vulnerable than dairy if the chosen scheme counts costs on a per kilo basis.

“Our industries are so integrated however, that dairy and sheep and beef have agreed to partner together to find a pricing system that works for all.”

The farm levy option is the fairest for recognising and rewarding what is happening on the farm.

As technology for reducing methane from stock is in its infancy, starting with the processor levy and moving to farmer levy may be simpler for administration. This also gives time for vegetation mapping tools to become easier and cheaper to use.

The Processor-Levy may favour breeders over finishers (the levy would be taken off meat income). Finishers will factor this in margins paid to breeders however. The stock agent spiel will now include reference to emissions tax. A Farm Level Levy may result in an overall cheaper farm emissions bill than the Processor Level Levy.

McIvor said the industry should find a balanced scheme – one that brings in revenue to match the level of rewards going out.

“It needs revenue to invest in future technologies to reduce emissions and to reward sequestration.”

Transition option might be best

Sam McIvor wants to hear what farmers think of the He Waka Eke Noa agricultural greenhouse gas pricing options. He says the organisation doesn’t have a firm position at the moment whether processor or farm level is best.

But changes to the options put forward by He Waka Eke Noa in January 2022 have seen a new option come forward – a transition option to go from a Processor-Level Levy to a Farm-Level levy over time.

“We consulted with target farmer groups and this came up as an option.”

McIvor sees the advantages.

“It gives time for farm mapping tools to improve, to make the administration cheaper and gives time for methane reduction technology to roll out.”

Farmers can voluntarily enter contracts to record either their emission reduction work onfarm, and/or their sequestration.

“The latest suggestion is to split them out as it adds flexibility for farmers who may not want to do both.”

The biodiversity study by Beef + Lamb NZ showed that, since 2008, farms have added to areas eligible for sequestration. The average area per farm is unknown, he says.

“But this is a real benefit to New Zealand and should be recognised.”

McIvor has a high degree of confidence that agriculture can reduce greenhouse gas emissions, although the organisation does not agree with the current government reduction targets.

“That is another issue and is being tackled by advocating to the Climate Change Commission.”

“We need a cost-effective and practical method to support these reductions and a workable scheme is what we need to be focused on developing.”