A stitch in time saves nine, goes the saying, meaning make repairs as soon as, or even before you see a problem to avoid much more work later. It’s a fitting adage for managing agrichemical resistance in the weeds, pests and diseases of our crops and forages, as Andrew Swallow reports.

After decades of agrichemical advances enhancing crop and forage yields, globally the trend is slowing, even turning, as regulatory reviews pull products from stores and resistant strains of weeds, pests and diseases evolve.

New Zealand lags Europe in these trends and has an opportunity to learn from northern hemisphere experience, Professor Fiona Burnett, chair of the United Kingdom’s Fungicide Resistance Action Group (FRAG) and Professor of Crop Protection at the Scottish Rural University College (SRUC), told delegates at the Foundation for Arable Research’s winter conference.

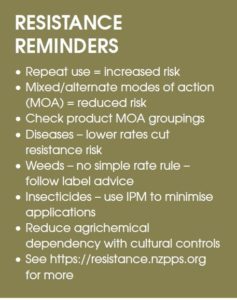

While her focus was on crop disease and fungicides, Country-Wide’s inquiries with local weed and pest experts since confirm her sentiments are echoed across the board: we have to get smarter in the way we use agrichemicals, not just on cropping farms, but on livestock properties too.

While her focus was on crop disease and fungicides, Country-Wide’s inquiries with local weed and pest experts since confirm her sentiments are echoed across the board: we have to get smarter in the way we use agrichemicals, not just on cropping farms, but on livestock properties too.

“Hopefully northern hemisphere experience can inform what you do down here,” Burnett told FAR delegates.

Fungicide resistance in crop diseases has been a problem ever since the first systemic products became available and as new products were launched sooner or later diseases evolved to overcome them. Development of resistance in UK crop diseases had been accelerated by tight rotations – two cereals followed by a one-year break crop being typical – and a combination of inadequate communication of and adherence to anti-resistance strategies.

In wheat, UK growers had routinely grown high-yielding but disease-susceptible – mainly septoria –varieties, relying on repeat fungicide applications to achieve crop potential, Burnett noted. The result was selection of septoria strains resistant to nearly every mode of action.

“We’ve broken the strobs, seen a massive reduction in azole efficacy, and there are emerging issues with the SDHIs.”

Meanwhile in barley, ramularia had become the dominant disease (Country-Wide, September 2017) with a similar history of fungicide resistance developing. Ramularia had “broken every form of available chemistry” and the UK industry’s management of it was a “how not to” example in terms of resistance, she said.

“We’re now totally reliant on the multi-site active chlorthalonil and we know we are going to lose that [due to regulatory withdrawal] in May next year. We will just have to take the hit. We are breeding new, more-resistant varieties but that takes a lot longer.”

Ramularia’s resistance to fungicides had developed despite FRAG flagging the disease as highly likely to develop resistance almost as soon as it was first diagnosed in UK barleys in the late 1990s, she added. Given most fungal pathogens’ ability to spread on the wind, collective responsible use of fungicides was essential.

“Don’t do what we did and play fast and loose with new [fungicide] tools when you get them. Everybody wants to use their clever little twists but it puts the whole industry at risk.”

Burnett later told Country-Wide she believed a cultural shift was needed so breaking stewardship guidelines became socially unacceptable, and growers and agronomists didn’t boast about doing so.

Burnett later told Country-Wide she believed a cultural shift was needed so breaking stewardship guidelines became socially unacceptable, and growers and agronomists didn’t boast about doing so.

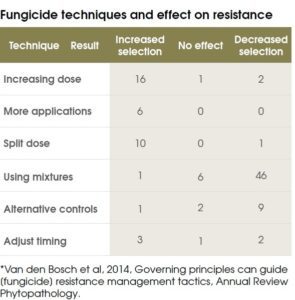

While there were nuances to resistance strategies and risks depending crop, chemical and disease, some general rules for fungicides could now be applied with confidence, following scientific review* of over 60 trials (see table).

Avoiding repeat use of a chemical, or chemicals with the same mode of action, on a crop was “really crucial” and adding mixing partners with an alternative mode of action “massively helpful,” she said.

The review paper also showed fungicides with multi-site activity were at less risk of being overcome, and laid to rest the long-standing debate about dose rate.

“With fungicides, the more chemical you’re using, the bigger the selection pressure, the bigger the threat of resistance developing.”

The reason for the latter is that any disease that escapes a high rate application through being a resistant strain “has the whole playground to itself” afterwards, resulting in an entirely resistant population, she explained.

Resistant weeds in your control

Herbicide-resistant weed problems are on the rise across New Zealand and all farmers – cropping and livestock – should heed warnings, AgResearch’s Trevor James says.

He’s one of the world’s leading academics on the topic and while problems are not yet as widespread in NZ as in some countries, they are on the increase.

“Resistance can prevent you growing the crop you want to grow,” he warns.

Equally in pasture situations, including hill country, evolution of a resistant weed population can cut production and increase costs, for example nodding and plumeless thistles in Waikato and Hawke’s Bay resistant to phenoxy herbicides, or Chilean Needle Grass in Hawke’s Bay resistant to dalapon.

As with fungicides, knowing a product’s mode of action group and avoiding repeat use from the same group year after year, or especially within a season, is a key measure to reduce risk of resistance developing.

“Make sure you know what is happening on your farm. Are any weeds becoming dominant and are you or your contractors failing to get control?”

Whether a herbicide is really necessary in the first place should be considered, and alternative controls used to reduce reliance on them, such as rotating crops and/or paddocks used for crops.

“If you do have to grow in the same place every year then make sure you’re using different activity groups or herbicides with more than one component.”

Assessing efficacy of, and developing alternative, non-herbicidal controls is a major focus for a five-year MBIE-funded programme on managing herbicide resistance which started last year, he points out.

Besides such preventative measures, the $10m project is also looking at: how to manage herbicide resistant weeds once they’ve developed; produce better ways to test populations for resistance; mine global data on weed-herbicide combinations to determine high resistance risk situations in NZ; understand why best practice advice hasn’t been heeded in the past and how to change behaviours now.

Unlike with fungicides, where a growing body of research shows reduced rate equals reduced resistance risk (see p82), there’s no such simple rule with regards herbicide rates. For some weed and herbicide combinations that is true, but with others robust rates are better. The best thing growers can do is heed label rate advice as that will be based on what is known about particular weed and product combinations with regards efficacy and resistance risk, he says.

Good biosecurity to prevent import of weeds, most likely as seeds or perhaps rhizomes or stolons, in feed, bedding, soil or on livestock, is also prudent.

“To a large extent herbicide resistance status of weeds on a particular farm is within the farmer’s control.”

Herbicide resistance reminders

- Resistance cases in NZ rising.

- Maximise use of cultural weed controls.

- Avoid repeat use of any one chemical mode of action.

- Monitor weed populations and responses.