After drought, the deluges

Between droughts and floods, a mix of work and play remains a priority for a young family on Banks Peninsula. By Annabelle Latz.

Between droughts and floods, a mix of work and play remains a priority for a young family on Banks Peninsula. By Annabelle Latz.

Mother Nature has her quirks. Emma and George Masefield on Canterbury’s Banks Peninsula know all about it.

The drought of 2020/21 is thankfully now a memory, but last summer was more of a contrast than they would have hoped for.

Last December 400mm of rain fell in 20 hours on their 430ha sheep and beef farm at Goughs Bay. They lost their road, the main bridge, power, water and phone for about 10 days.

For 17 weeks they used the neighbours’ farm and a 15 minute drive across the paddocks. This enabled them to transport about 60 bales of summer ewe and lambs wool out, to allow room for the winter shear.

George and Emma managed to drive a farm vehicle across sodden paddocks to their neighbours’ house. For a number of months they would motorbike there to collect the awaiting vehicle for running errands and checking their other blocks. Farm and food supplies were once helicoptered in.

Goughs Bay Road had a major overhaul in the mid-year, with new culverts, widened corners and a much-improved surface with little corrugation.

Just when things were getting back to normal, in mid-July, a hefty 570mm of rain fell in three weeks, damaging farm bridges, flood gates and fences.

“At least we’re getting good at fixing things,” George said.

They did save money by not fertilising, because it was too wet.

Their whole flat crop growing area was covered in silt after the December event, With a digger and a tractor they shifted 5500 tonnes which is now stockpiled and worthless.

The Masefield family have farmed at Goughs Bay since the first four ships sailed in to Lyttelton.

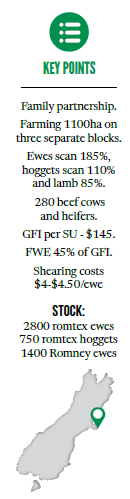

George (31) and his wife Emma (28) have shifted the farming focus from a store to a finishing operation. They have been in a business partnership with George’s parents John and Carol since 2016, operating under Goughs Bay Farms. They have two children; Jack, 5 and Matilda, 3.

George says it is all about having options.

“We are fortunate we are in partnership, it means we can put our mark on the place.”

The Masefields run 4200 Texel and Romney ewes on three separate blocks on the peninsula, each finishing its own lambs.

The original 430ha home block at Goughs Bay is the breeding unit, the ‘bread and butter’ for the farm, where consistency is key and breeding quality stock means they always have a market.

The Texel/Romney ewes go to a maternal Texel/Romney ram. They run 40 rams, bought from Sam Holland in Culverden, North Canterbury. Born on hard country, George said they do well and have a good wool yield.

“We do select our rams to have a good fleece, because if we’re paying to get it shorn off we might as well get a decent one.”

Their 400ha block at Pipers Valley in nearby Duvauchelle is the terminal block, a ‘motley crew’ of Romney/Texel ewes which go to a Texel ram.

The third block is a 330ha lease block at nearby Chorlton, running all Romney ewes and putting a Texel ram over them. They pre-sell about 400 ewe lambs to a local farmer, and finish the rest.

Having three different blocks is a strength of the farm, George said, meaning there is normally somewhere that has feed if they need to shuffle stock.

George and his father are full time, and one farm worker who doubles as a mechanic, on deck two days a week most of the year, and full time from October to February.

Collectively, they put 750 hoggets to the ram, which scan between 100-110%. If they miss the first time, they get a second chance.

The ewes scan at 185%, and lambs at 144%.

George says they are getting too many triplets, so put in more Romney to close the gap between scanning and lambing.

‘If we’ve done 160% for the triplets we’ve done bloody well.”

All the ewes are shorn every six months. Replacement ewe lambs are shorn in December, and fattening lambs mid-January.

This year they killed 6500 lambs which averaged 18kg carcaseweight (CW). They sold 1100 stores averaging $130, well up from the average $90 the previous year. They also bought some lambs from Taupo because there was the feed, killing them at roughly 38-40kg liveweight (LW) and making a $47 margin.

They run 40 rams, which go out with the ewes from mid-March until the start of April, lambing from mid-August until the beginning of September. The hogget programme runs six weeks later. They’ll slaughter about 700 lambs straight off the ewe, as long as they sit at 40kg LW to meet Alliance’s yield contracts.

“Our goal is to get that number up a bit higher in the near future.”

Condition scoring isn’t something they do routinely, only when they’re in challenging times. As a rule they weigh fattening stock to give true indications, and at least every week they kill lambs.

Everything receives a five-in-one at tailing time, and a drench pre-weaning.

“Drench, dag and weighing is pretty much the summer plus a few faecal egg counts.”

They try to keep things as simple as possible.

“If you chop and change all the time, you’ll get yourself into a hole at some stage.”

Cropping ups the pace

Selling on schedule to Alliance is how the Masefields have operated for 35 years, although until five years ago nothing was fattened beyond store.

There has been a change in pace since the family partnership began in 2016, including investing in development of land by cropping, upgrading water schemes and fencing.

Cropping is a fairly new part of farm life at Goughs Bay. With a tractor, a spray unit, a drill, cultivation gear, and a spreader, they can do every aspect of this work, as there are no contractors nearby.

“We buy decent if not new gear, because no one likes breakdowns, and things always break down when you don’t want them to.”

They crop 130ha in brassica and red clover on the flats, and break in a bit of hill country every year too, as environmental conditions allow.

The crop cycle is fairly simple, the calendar year starting with brassica, then brassica and grass for winter, back into brassica for spring, then clover and grass for summer. George admitted he does get ‘hare brained’ ideas if he spends too long driving in circles on the tractor.

“He can change his mind five times in a day,” Emma said.

The goal is to get five years out of the clover, which is achieved by fertilising mainly with heavy sulphur, spraying thistles, and spraying the grass every winter.

“It’s too much of a valuable asset to try and skimp the costs, because the more you put in the more you get out,” George said.

With farm regulations on the increase, all crops need to be in pre-Christmas to mitigate the sediment run-off in autumn.

They aim to fertilise half the farm each year, which is the recommendation from Ballance, and soil-test native country. The crops get DAP at sowing or drilling, as and when needed. Due to the drought in 2020/21, only the hill country received nitrogen and DAP.

“At least with our system we always have the option of selling stores. Having the Texels through them means they’re more appealing if you get a pinch, they’re easier to sell compared to traditional maternal breeds.”

The Olsen pH sits fairly high on Banks Peninsula, so they don’t try to adjust it.

“We work with Mother Nature, if she allows us to grow a wee bit more grass, we do,” George said.

There was no fertilising this year, due to the two significant rain events.

Despite the upheavals from a wet year, farm life continued.

The average rainfall is 1000mm/year, but they can get a feed pinch pre-lambing. That’s when the winter crop programme kicks in. The ewes can be shifted on to the brassicas and grass so the paddocks can get a rest before lambing starts. They also buy in balage if it’s needed.

They put the ewes and 10-day old lambs on to red clover.

“With a change of breed and extra work we are now able to finish everything.”

Emma runs the business side of the farm, and has found the Rural Women’s Trust courses invaluable. Coming from a vet nursing background in North Canterbury, she had a lot to learn when she joined George on the farm, and wanted to be fully involved.

“I now understand the farming business better. Bank managers want you budgeting, they want you to be in control of everything.”

Emma works two days a week as a vet nurse in nearby Little River so between that, farm life and having a young family, life is busier than ever.

Cross gives options

They run 280 Angus/Hereford cross cows and heifers, which are put to an Angus bull. George likes the cross, as they used to be straight Hereford, but they are beginning to lean towards predominantly Angus.

“It just gives more options.”

They buy Angus bulls from Jono Reed at The Grampians in Culverden. Their eight bulls onfarm were bought as two-year-olds, which is the first year they are used for mating.

“We have faith in Sam with the rams and Jono with the bulls that they’re doing the best job they can, and we can reap the rewards.”

Heifers will calve mid-August, the cows a couple of weeks later.

Each year they sell 70 steer calves to a regular customer, the rest are sold as 18-month-olds as stores. Their store steers sit between 480-500kg LW, the prime steers 540-600kg LW. Most heifers are killed as 18-month or two-year-olds when they’re more than 430kg LW, they also keep about 50 replacement heifers each year.

“The cattle programme has stayed the same over the years, it works and it gives us options to hold or sell.”

Like everyone, their inputs are higher, but the payouts are higher too.

George says they are paid more for their lambs on a scheduled price so are making the same margin as before.

“The bank hasn’t come knocking yet, so we must be doing something right.”

They’ve been thankful for their conservative approach with their sale prices, and they overestimate expenditure. It’s the same with the scanning percentage.

Emma said having a great relationship with the bank manager is essential, as they can bring up anything and not feel intimidated.

“We never feel like we’re asking silly questions.”

Signs that they’re performing well aren’t just in the balance books. It is pride in what goes on the stock truck, as well as being able to live comfortably even with the hefty mortgage.

George says upholding sound relationships with their bank manager and their stock agent is important.

“If everyone is happy to help us, we must be doing the right thing.”

Lifestyle is important

Emma says life at Goughs Bay is about having a good network of people, together taking on the challenges and continual lessons.

“It’s a great life for teaching the kids about responsibilities, the environment, and life and death.”

She says Jack is up every day at 6am ready to go. At the age of five he can shift breaks and weigh lambs by himself.

“Life is non-stop and it can be all hours of the day, but I think we reap the benefits.”

Time away from farming is important too. It may be a family hunt, riding the horses and ponies on the farm or Emma competing in show jumping. Or George taking some of his sheep dogs to local dog trials or the kids for a swim in Christchurch.

“If you get tied up in the dollars and cents you might lose sight of what you’re here for,” he says.