BY: ROBERT PATTISON

Consumers around the world don’t buy wool; they buy woollen textile products of which wool is one component. And while coarse wool prices are at an all-time low, woollen product prices are increasing.

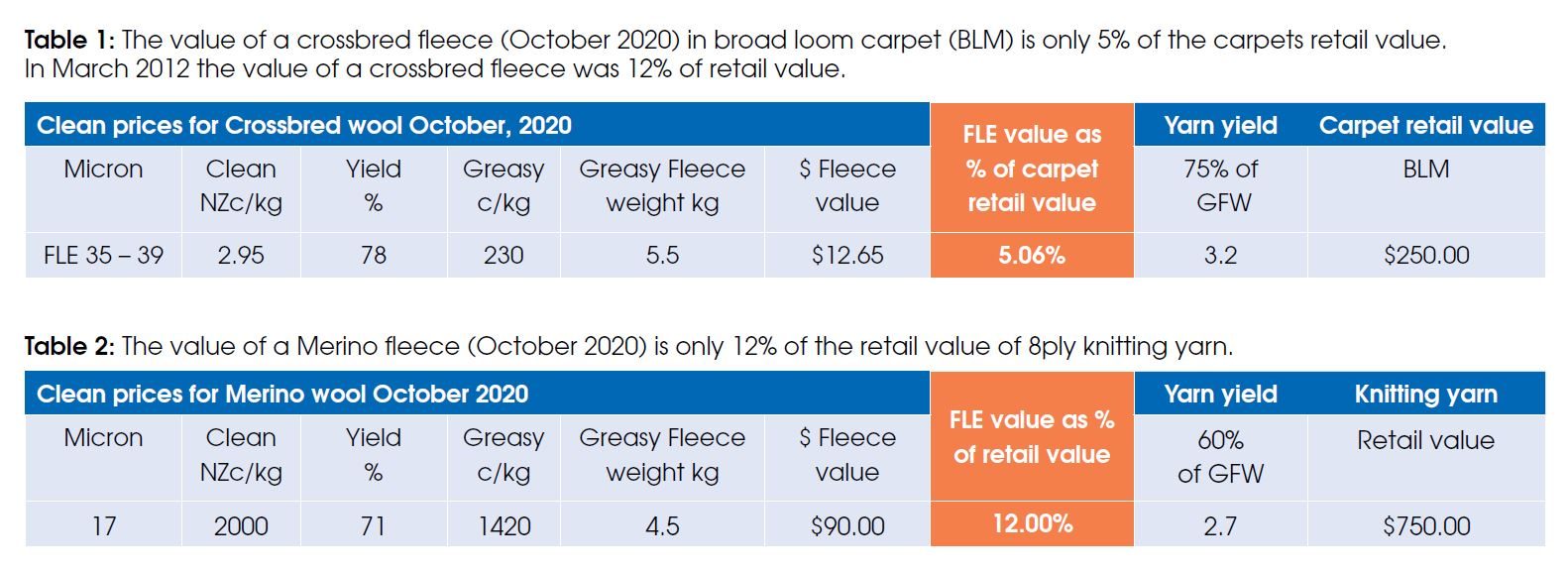

Table 1 shows that the value of coarse wool (35-39 micron) is only 5% of the retail value of a metre of woollen broadloom carpet. The margins to be made from wool are small compared with the retail value of woollen products.

Table 2 shows the same with woollen apparel products. Merino wool prices have been at record levels, but the value of a 17 micron fleece is still only 12% of the retail value of knitting yarn.

Despite greasy coarse wool prices dropping below $2/kg, the international retail value of products made from NZ wool is worth more than NZ$5 billion; that’s 10 times the FOB export value of NZ’s wool clip.

NZ coarse wool is converted into a huge range of products – knitting and carpet yarns, carpets and rugs, upholstery, furnishings, bedding, clothing and novel end uses such as tennis balls, insulation, industrial products, felted materials and, more recently, shoes and surf boards. Then there are health and medical applications.

But very few farmers invest in adding value to their wool beyond the farm gate.

At present, sheep are shorn in their age groups – ewes, rams, hoggets, lambs – and the wool sorted into various lines for quality (style), colour, staple length, fineness and acquired faults. The wool is then pressed into bales with line descriptions recorded and sold to wool merchants, wool brokers (contracts, on-line by description, or at auction) as is where is.

Sheep farmers take no further responsibility other than accepting what they consider is the best price available at time of sale.

The buyers are wool exporter companies who interface with manufacturers. Each farmer and company in the pipeline operates independently and seeks to make a profit from each transaction. These greasy wool traders are all price takers.

They provide a service to farmers and the international textile industry.

Developing equity partnerships with manufacturers to capture a share of the product value may be one way that coarse wool sheep farmers don’t have to rely solely on the price of greasy wool inside their farm gate.

Historically, NZ wool promotion has targeted the biological, environmental and sustainability properties of wool. In fact, billions of dollars (NZ$4.1 billion from 1945 to 2009) was spent on research, product development and promoting the attributes of wool to consumers. But history has shown farmer-funded market support schemes and branding programmes for greasy wool have been unsustainable.

With the average coarse wool price now under $2.00/kg greasy, there has clearly been market failure and the majority of coarse wool sheep farmers haven’t supported their unique fibre since they stopped paying wool levies in 2009.

Since then there has not been a formal collective wool industry research fund or a cohesive market or industry funding strategy.

The exception has been farmers who invested in companies such as Wools of NZ, Primary Wool Co-Operative and Carrfields Primary Wool (CP Wool Partners), and a number of independent farmers and businesses that have privately funded and ventured into manufacturing and adding value to wool.

There are also many wool trading businesses working independently investing their own capital in their product and market development programmes.

Along with the NZ Wool Exporter companies, they all operate independently and compete in the international market for NZ wool. Each business seeks to make a profit and pay shareholder dividends. They also endeavour to pay their farmer supplier/shareholders premiums (either at auction or private contracts) for specific types of greasy wool.

Each company has to compete on price/kg to attract farmer suppliers and at the same time compete on price/kg to their clients along the supply pipeline. This means the businesses operating in the greasy/scoured wool market are margin traders.

History clearly shows that if coarse wool sheep farmers continue to rely on fibre branding and marketing strategies to increase greasy wool prices they will be disappointed.

Past expenditure of hundreds of millions of wool grower levies on generic promotion for NZ strong wool, and for branded interior textiles such as carpets, rugs, bedding and upholstery, has been successful at increasing consumer awareness and product demand but hasn’t halted the long-term decline in wool prices at the farm gate. There haven’t been any joint venture initiatives developed for a share of the added value to be passed back to wool growers.

International woollen processors and manufacturers have a significant investment and commitment to wool, but they are also able and willing to use alternative fibres when NZ coarse wool is deemed to be too expensive. In order to avoid substitution, coarse wool prices have to retain their long-term price relativity to synthetics and cotton in the international textile fibre markets.

Rather than focusing on initiatives to increase the price per kilogram for coarse wool, developing equity partnerships with manufacturers in NZ, North America and Europe may be what is required for sheep farmers to capture a larger share of the product value.

In the past 20 years specialist wool organisations such as the NZ Wool Board, Australian Wool Corporation, International Wool Secretariat, and South African Wool Board have all been disestablished. In the mid-90s they collectively had more than $1 billion in reserves. But the reserves were spent trying to artificially support and increase the price/kg of wool.

There have since been many farmer-funded companies that have attempted to fill the void, but they have also been unsuccessful at being able to sustain or increase wool prices and the companies have failed despite the appointments of many farmer and professional directors.

With a multitude of company failures, and all the reserves gone, the international market for NZ wool has been left to operate internationally in a free market without an industry body.

There is plenty of evidence that many NZ and international companies have launched successful marketing campaigns for their products using images of NZ scenery to support their environmental and sustainability stories. We also know that marketing stories with a green perception help sell a product.

Equally important is that the chemicals used for early stage processing, such as scouring agents, fibre treatments, lubricants and dyestuffs, are all independently assessed as being environmentally friendly.

To capture a greater share of the global $5 billion woollen product value at consumer level, sheepfarmers and government agencies should be partnering with businesses that have the expertise and technology required to convert coarse wool into high quality woollen products.

NZ has factories with modern machinery and people with the entrepreneurial skills to take coarse wool products to international markets.

The immediate problem for sheepfarmers is that there is no collective capital fund left to finance any new business proposals or ventures.

Fortunately, the Strong Wool Action Group has secured $400,000 (half from four meat companies and half from the Ministry for Primary Industries). This has allowed it to appoint an executive officer. The challenge for him will be to convince coarse wool farmers and government agencies to invest in the coarse wool industry outside the farm gate as well as implement an industry-wide strategy to halt the long-term decline in wool revenue inside the farm gate.

- Robert Pattison is a wool consultant based in Canterbury.