Wool on the floor

The returns, or lack thereof, for coarse wool have been a thorn in the lamb producer’s side for years now, but Nicola Dennis says there are some good options for wool growers.

The returns, or lack thereof, for coarse wool have been a thorn in the lamb producer’s side for years now, but Nicola Dennis says there are some good options for wool growers.

Fingers are crossed that new technologies, or better marketing of woollen carpets and drapes, will put the ‘strong’ back in strong wool. But, for now, it remains the much poorer cousin to the snugglier fine wool that’s working its way into a growing number of fashion items.

If you find yourself looking at negative wool returns then you have two options. First, keep on keeping on. Maybe you feel that the strong wool sunrise is just around the corner and you are happy to write off the shearing costs in the meantime. You might not even be that happy about it, but sometimes it is nice to have something innocuous to channel your rage towards. You’ll get no judgement from me, I happen to think that low-key outrage is one of the screws holding society together.

The second option would be to transition away from strong-wool breeds. You could introduce some fine wool genetics into your flock to target the higher value wool markets, or you could do away with the wool clip altogether by transitioning to a shedding breed.

Massey University has been crunching some serious numbers to model what production, profit and cashflow could look like for a Romney flock breeding up to a fine-wool composite (3/4 Merino, 1/4 Romney) or to a fully shedding Wiltshire-Romney crossbred. The Massey experts found that both of these strategies are financially favourable in the long term. The transition was estimated to be worth an extra $100–124/ha in operating profit for the Merino route, and $25–55/ha for the Wiltshire route once complete. There are some pinch points in the middle of the Merino route when the rise in wool returns lags behind the drop in lamb production, but if producing a tidy wool clip is your strong suit, then it’s worth taking a temporary hit for a long-term gain.

If lambs are a higher priority, then follow me. We are going to take a closer look at Massey’s Romney to Wiltshire research. Don’t worry about the wool folks, the editor can find someone much more skilled in wool classifications to talk to them. My paddocks are stacked with wild, woolless Wiltshires, I barely even know what wool looks like.

Let’s see what Massey has to say about transitioning you away from shearing.

Computer sheep and assumptions

This study was done in a computer model, which is great because it means we don’t have to wait around for scientists to document the 13–16 year transition period on real farms. It also means that the people writing the model had to make choices about the type of scenario they were modelling.

Picture yourself on a 530ha East Coast North Island hill country sheep and beef farm. This farm maintains a 2066 Romney ewe flock which consumes 60% of the total farm feed. Those are very specific numbers, so I expect we are also imagining a farm manager who is very good at keeping tally. The mature sheep yield, on average, 5.2kg of greasy wool each with an average fibre diameter of 36 micrometres. For the base scenario the farmgate wool price is $2.15/kg greasy, or roughly $2.95/kg clean. This paper was written in the deep, dark days of 2020 when wool was a very hard sell. But even now, a very nice crossbred fleece might achieve $3/kg clean these days. “Might” being the operative word.

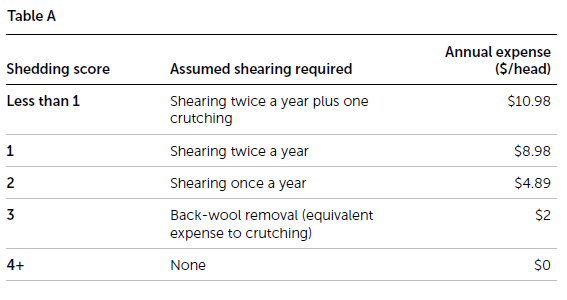

In computer land, the ewes had their first lambing at two years old and were culled for age after they had completed rearing their fifth crop of lambs at six years old. There was a death rate of 5.2% across the ages and a 25% replacement rate, and replacements were sourced from within the flock. The Romneys are booked in for twice-yearly shearing, plus a crutching at an annual cost of $10.98/head.

When modelling the Wiltshire transition, two endpoints were considered: either transitioning up to a Wiltshire (which is three generations of crossbreds) or going an extra generation to make a straight-bred Wiltshire. Both endpoints were assumed to deliver a full-shedding flock, but the offspring from the 7/8 flock might have a small proportion of partial shedders popping up in the mix. A 50% selection intensity was applied, meaning that the cross-bred ewe lambs were only retained as replacement if they had above average shedding scores in January (when they were about five months old). This is referring to a 0 to 5 shedding score where 0 is no shedding and 5 is completely shed. Of course the modellers had to decide on what the shedding score meant for shearing costs in Table A.

There is always a wide variation of shedding in crossbreds. Some will inherit almost no shedding and some will be hard to distinguish from purebreds. The computer is assuming that the top 50% of first cross (1/2 Wiltshire, 1/2 Romney) will have an average shedding score of 3 which means that there is some wool on the back of the sheep that would need to be removed, but the legs, belly and bum are clean.

It was assumed that there was no difference in lamb production or health expenses between the breeds. That computer lambs grew at 100g/day post weaning and 55% were killed out at 18kg carcase weight. The rest were sold as store lambs. There was no money spent on the shearing of the Wiltshire-cross lambs as they were all expected to be tidy enough for sale (saving an estimated $3.71/head). I can attest that my processor has never baulked at the occasional woolly backed lambs I have sent in, even if they do look like turtles.

The grading up process

The simulated grading-up process was what you would expect. Wiltshire rams were put over the computer Romney ewes and the best half-n-half lambs were used as replacements. Because this farm isn’t mating hoggets, the following year will still only yield the first generation half-n-halfs.

In the third year, the first crop of half-n-halfs would give a pool of 3/4 Wiltshire replacements (topped up with the best of the half-n-halfs). Once the 3/4 Wiltshires started producing as two year olds you would have some 7/8ths to choose the replacements from. This might be where you stop worrying about grading up, if you aren’t fussed on having a definitively naked lamb crop. Otherwise it would be a couple more years before the 7/8ths started producing full-blooded Wiltshires. During the grading-up process, the lesser-Wiltshire-cross animals were culled a year earlier as five-year-olds, to make way for the higher-Wiltshire crosses coming through. Once the desired Wiltshire content was reached, the culling age reverted to six years.

I might be exposing myself to ridicule, but I have never culled for age alone. I have some 10-year-old Wiltshire ewes that first lambed as one-year-olds out in my lambing paddock. If they still have teeth, feet and udders then I don’t see the point in swapping them for a hogget that might not be able to count! But, we can’t expect the computer to base its culling decisions on the fondling non-existent sheep, so off with their six-year-old heads.

The results

Enough with the assumptions: let’s look at the results. First let’s look at how long the transition is expected to take. In the model, it took 13 years to get to an entirely 7/8th Wiltshire flock and it took 16 years to transition the flock to full Wiltshire, although there was no shearing after the seventh year of transition. If that all sounds too long, then remember that the hoggets weren’t being bred and there were some reasonably tight selection criteria on the replacements. So, there is room to speed things up if getting to the finish line is the main priority.

During the transition, ewe numbers were elevated as the farm cycled through the new-breed mixes to get to the final goal.

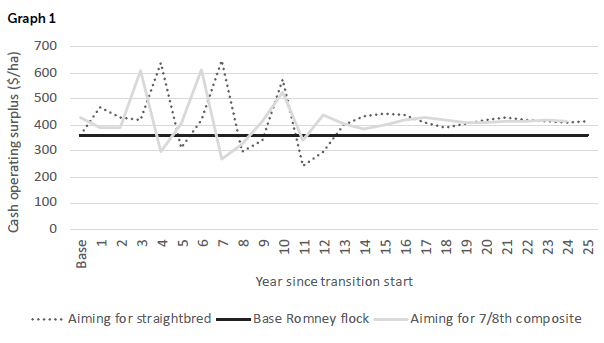

At times, there were an extra 500 ewes on the farm. This means the number of lambs and the cull ewes (and therefore income) are all higher during the transition period. Meanwhile, the wool revenue takes a dive and is completely eliminated after eight years. Occasionally during the transition, the operating profit drops slightly below the base (Romney) scenario. See Graph 1 that I adapted from the study results.

As you can see in the graph, there isn’t a whole lot of financial difference between transitioning to a straightbred flock or aiming for the 7/8th composite. In reality, the purebreds might have cost savings that aren’t accounted for in the model, such as being able to forgo tailing or fly treatments, or the surplus ewe lambs might command a premium as breeding replacements for other farms, rather than being sold on the store or slaughter market. But then again, a bit of hybrid vigour in the composite could mean that they perform better on lamb production.

Massey also looked at the “break even” wool price, or how low the farmgate wool price needs to be for the Wiltshire strategy to be worth it. The break-even wool price was estimated at $4.15/kg greasy or $5.70/kg clean. The authors point out that these kinds of prices haven’t been available for strong wool since 1989. Ouch. Double ouch when you realise that $5.70 of 1989 money is actually worth $12 after accounting for 33 years of inflation. I wonder, if there were enough farmers transitioning to Wiltshires, could a shortage of strong wool have the remaining Romney farmers partying like it’s 1989? Or perhaps shearers would exit the industry and drive the cost of shearing through the roof? And, surely woolshed maintenance, which was not accounted for in the model, is not cheap?

Anyway, the authors point out that the Romney farmers don’t have to shear twice a year and that $4.09/ewe could be saved by switching to once-a-year shearing. Although having woolly ewes during spring lambing might decrease ewe survival and lamb growth if ewes are more prone to becoming cast.

That’s one thing you can confidently say about Wiltshires, their sleek and athletic composition means they are very unlikely to get cast. But then again I’ve never seen a Romney try to stag leap out of a set of cattle yards. So it’s horses for courses.

Ultimately, it seems that transitioning to Wiltshire or to a fine wool composite is worth the effort, if you have the inclination and patience to do so. But, when it comes to breed selection, you must follow what’s in your heart. You spend a lot of time looking at your stock and you have to like what you see. Although, your accountant is going to say the same thing about your books…

Real life transitions

With the modelling complete, Massey is now undertaking a real-life Wiltshire-transition trial on its Riverside Wairarapa farm.

This will provide more data to ensure the academics’ assumptions in computer land were appropriate and applicable to gumboot land. That is the great thing about modelling – it allows you to piece together what information is out there, but it also highlights gaps in the scientific knowledge that are waiting to be filled. I, for one, am waiting with baited breath to see if there are noticeable changes in temperament and ewe-health costs during the transition.

- The full, 24 pages of modelling results are available here: https://bit.ly/wiltrom Farrell LJ, Morris ST, Kenyon PR, Tozer PR. Modelling a Transition from Purebred Romney to Fully Shedding Wiltshire-Romney Crossbred. Animals. 2020 Nov 7;10(11):2066.