What’s your approach to culling ewes?

Massey University Professor Anne Ridler and Otago-based Farm Consultant Peter Young urge farmers to take the time to make more considered decisions when culling ewes as it could pay dividends. Words Sandra Taylor.

Studies have shown that on average, 29% of breeding ewes are leaving their flocks every year through culling and deaths – and this can be expensive.

Anne Ridler, Associate Professor of Sheep and Beef Cattle Health and Production at Massey University, says it means that farmers are having to put enough ewes to the maternal sire to breed sufficient replacements, limiting the number of ewes that could be used to breed higher-value terminal lambs.

“On average farmers are culling between 20–25% of their ewes every year and it can be expensive to replace a lot of ewes.”

In 2021, Anne and her team looked at the culling policies on 36 farms evenly split across the North and South Islands. She says they wanted to know what factors farmers were culling on and why. They also visited the farms when they were checking ewes for culling and found 9% of ewes were culled on age, 5% on teeth defects and 2.5% on udders.

“Be really clear about what criteria you’re culling on and why you are doing it, not just, for example, because they are ugly sheep.” – Anne Ridler, Associate Professor of Sheep and

Beef Cattle Health and Production, Massey University

Anne points out that culling is usually done at a busy time of the year, when there are a lot of other operations happening at the same time, but it can mean productive ewes are being culled for no sound reason.

She says farmers are making an instant prediction on what’s going to be a productive ewe the following season and she is encouraging farmers to be clear about what and why they are culling ewes.

“Just be really clear about what criteria you’re culling on and why you are doing it, not just, for example, because they are ugly sheep.”

Where there are lots of staff, Ridler suggests ensuring all staff involved in the culling process are clear about the reasons for culling, and cross-checking is done to ensure consistency.

Udder defects are often a reason a ewe is culled and ideally udders should be checked for defects four to six weeks after weaning. She says udders need to be felt, but too often they are just getting a cursory glance, rather than being properly examined and this can result in defects being missed.

Production-based culling

Otago-based Farm Consultant Peter Young believes there are opportunities for farmers to include more production-based culling in their flocks to support more efficient and profitable performance.

“Any culling that improves the average reproductive performance of a flock also enables more ewes to be mated to terminal rams. This benefits the meat production efficiency of the whole flock through the increased use of terminal rams and the added benefits of hybrid vigour in those terminal lambs.”

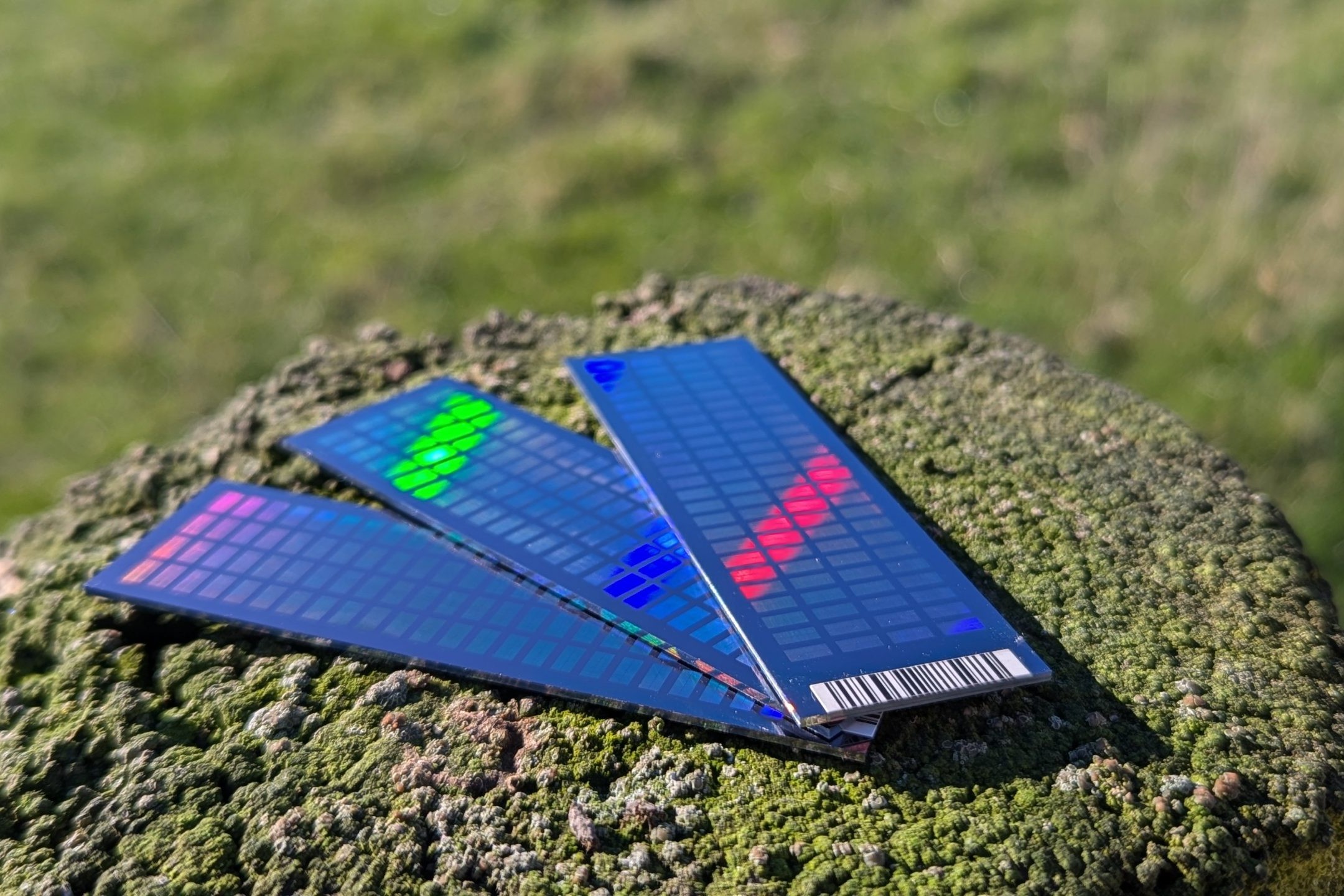

Peter says EID tags are a valuable tool to allow farmers to make more informed culling decisions, as they give farmers the ability to track year-on-year performance of individual ewes.

This means ewes that are repeatedly conceiving singles, have low body condition scores, and are wet/dry can be culled. But this does require monitoring and the appropriate use of information.

Peter says the age at which ewes should be culled from a flock varies between properties and should be driven by the percentage of deaths that occur in the oldest age group compared to the average death rate of the ewe’s flock.

He says there will continue to be debate over faster genetic turnover versus longevity, but in harsher environments, proven performance of older ewes is a valuable asset if they have remained in the flock with robust performance-based culling policies in place.