Unlocking beef returns from the top down

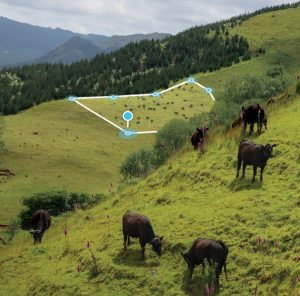

Virtual fencing technology is showing the returns of daily rotational grazing on steep, hill country beef farms.

Words by Sarah Perriam-Lampp Photos by Michael Lahood.

The curiosity of the virtual fence

The curiosity of the virtual fence

The sound of moving cows on James Parsons’ hard North Island hill country has rapidly evolved from the deep bellow of a huntaway piercing the early morning air, to the quiet beep of Halter’s virtual fence system.

As a hill country farmer, he had been watching the virtual fencing space on dairy farms for a while with his interest in pasture utilisation being the key metric to improve farm margins.

“Halter is a technology that can make best practice possible and bring hill country farming into a new era.”

His impatience led him to talk to the Halter team at the March 2023 Northland Agricultural Field Days to discover they were working on a specialist beef product called Halter Base which launched in December 2023. “We have always known that there’s a lot of value we can add to a beef operation and that many farmers were watching and waiting,” explains Founder and Chief Executive of Halter, Craig Piggott. “Hill country farmers can literally see the value as they can see the feed going uneaten on the tops of the hills that the cows aren’t grazing. This means they can run more cattle per hectare.”

By November 2023, Matauri Angus in the Tangowahine Valley, north of Dargaville had wearable devices on their cows and James had many theories and calculations to make him confident; but was still left with many questions.

- Are we pushing the boundaries with collars on hill country with beef cows?

- Will the cows freak out because the uncollared calves have access to wander around a 20 ha paddock, but the cows are contained to 1 ha of that paddock?

- When we try to shift the cows, how will the cows manage their movements around a bluff?

- How will the team of staff handle the new technology?

- How big an issue will our current water infrastructure be?

But as he had seen the benefit of subdivision, particularly in bull cell systems like techno beef, the main question was always ‘could extensively grazed low performing farms be turned into high producing ones through a similar farm system using virtual fencing?’

James, former Beef + Lamb NZ Chairman and current AgFirst Northland Director and Consultant, had run the many spreadsheets and scenarios from Farmax on what he could only work out to be a compelling return on investment for hill country beef farms.

“The system is a game changer. There are three levers to pull to improve sustainable and profitable production; more pasture grown, pasture eaten and better pasture quality. Halter is a technology that can make best practice possible and bring hill country farming into a new era,” says James.

Return on Investment

The ability to unlock vast areas of poorly utilised pasture on hill country and leverage that land could help counter industry headwinds, says Craig.

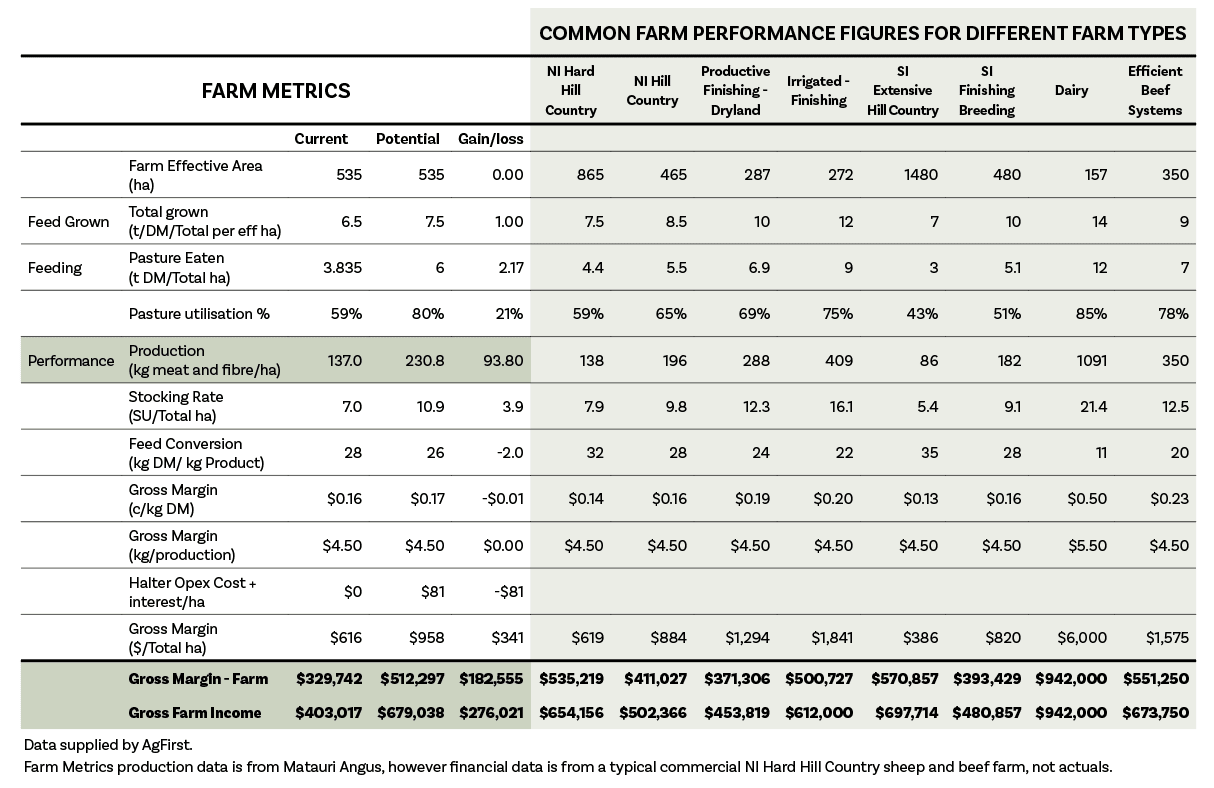

Pasture utilisation on beef farms ranges from 40-70%, compared to 80-90% in dairy systems. James believes if we could achieve 80%, that’s an additional 1-2 tonnes of drymatter eaten. Not to mention improved grass growth, feed quality and environmental benefits.

Sheep and beef farmers aren’t as attuned to pasture utilisation as a metric and James had to lean into research on hill country utilisation by Lincoln University to validate his baseline pasture utilisation of 59% prior to Halter. He calculated this from pasture grown on farm and compared that with feed eaten (measured in Farmax).

“Rotational grazing is proven to be better for grass regrowth and quality, with daily allocations and back-fencing preventing overgrazing and undergrazing and optimising feed intake,” explains Craig. “It’s the rotational grazing of daily shifts that can significantly improve productivity per hectare, and Halter also has no extra fencing or labour.”

James believes the productivity gains don’t stop there as pasture utilisation is just one of three levers. With better grazing management will come extra grass growth, the second lever. Rank undergrazed areas of the paddock don’t grow to their potential and neither do overgrazed areas of the paddock. He believes there could be an extra tonne of drymatter production on offer with better grazing management. That will result in more leafy quality feed which animals digest faster, the third lever of production. This leads to better animal growth rates measured through a more efficient feed conversion efficiency.

“Each of the levers has a flow on effect to improve gross margin per hectare. If you grow more feed it’s only as good as how you utilise it. If you don’t overgraze, ‘grass grows grass’, and ultimately feed quality improves which is of higher energy and equals more kilos of beef per tonne of grass,” summarises James.

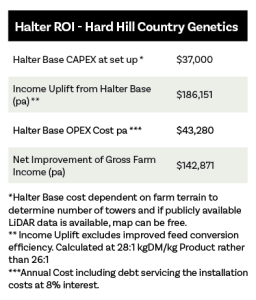

Of the 535ha effective, James was able to establish that if prior to Halter they produce 137kg meat and fibre per hectare (7su/ha rate) that came from eating 3.8t DM/ha with a 59% pasture utilisation, he has a feed conversion figure of 28kg DM / kg product (see table overleaf).

In trying to calculate the opportunity before committing to Halter, James assessed utilisation could move from 59% to 80%, which he has seen achieved on bull techno systems. Dairy farmers frequently achieving utilisation of better than 80% was another reference point. The key is small paddocks and ideally daily shifts; something that, until now, has been highly impractical for hill country. By contrast, currently at Matauri Angus many of the paddocks sit at around 15-20ha. So prior to Halter, cattle were shifted weekly to every two weeks, depending on mob and paddock size.

“As farmers we are constantly chasing improved utilisation, but balancing that with feeding the animal well,” says James. “On our farm we believe, with daily shifts through Halter and improved water infrastructure to enable that, we can move from 3.8t drymatter eaten/ha to 5.2t. That utilisation lever alone, after the cost of Halter, will deliver an extra $74k gross margin or $138/ha.”

Overall, James has identified a potential return on investment for using Halter is $182,555 of gross margin for the farm’s operation after the cost of Halter and debt servicing extra livestock to eat the additional feed.

The second lever increased pasture production, combined with improved feed conversion efficiency (third lever) and an 80% utilisation, shows the potential on offer is an extra 94kg in meat production per hectare equating to a $341/per hectare/gross margin increase.

Overall, James has identified a potential return on investment for using Halter is $182,555 of gross margin for the farm’s operation after the cost of Halter and debt servicing extra livestock to eat the additional feed.

“We won’t achieve this straight away, it will be highly dependent on our skill as managers,” said James. “But even if we get half of that, it is a compelling proposition. As the industry embraces virtual fencing technology I am confident that this potential is achievable. But it will take some significant system changes to unlock it.”

The discovery of creep grazing

The discovery of creep grazing

Craig says that if you are using 20% more of your pasture then you are increasing your farm’s productive area and therefore stocking rate by 20%, before you factor in the financial benefits of weaning weights.

One of James’ initial questions as he set out on his investment into virtual fencing was ‘will the cows freak out because their uncollared calves will wander around a 20ha paddock, but the cows are contained to 1 ha of that paddock?’

He discovered the calves happily leaving their mother’s side to graze afar without distressed cows. There was also an increase in weaning weights. Despite a dry summer and autumn, Matauri Angus first calving heifers calves were 12kg ahead of last year’s calves. The theory is that calves being able to ‘creep graze’ ahead of their mothers on the fresh grass, with no competition for the higher energy feed with the older animals, impacts these results.

“The benefit of having the optimum cattle-to-sheep ratio in our large hill blocks means that the sheep benefit from the cows eating previously unutilised feed,” shares James.

He estimates that within a paddock the late summer cover along the ridges and steeper faces are around 3.5t DM/ha whereas the bottom of the valleys is more like 1.2t DM/ha.

James, alongside his business partner and farm manager Travis Pymm, were some of Halter’s first partner farmers when the agritech company expanded into the beef market in December 2023. Halter were hands-on in the initial training of cattle, and after months of further trials, beef cattle are now typically trained to shift daily in under a week. There are some differences between Halter’s dairy system and Halter Base for beef in how the vibration or beep on the solar-powered smart cow collars works.

“The beeps are used to guide animals back into a break if they cross a virtual fence, the vibration is used to indicate to the animal where to go for the next break. There’s no rush, in summer it can take 4-5 hours for them all to move to the next break whereas in spring it’s 20 minutes,” says James.

He says it’s usually the farmer who’s harder to train than the cows, to use and trust the system. Their biggest challenge is water infrastructure. A trough at the bottom of a 20ha paddock is a constraint when it comes to holding a mob in 1ha at the top of the hill. To achieve the gains, James says they need to invest in water. But he believes the return on investment from that new water infrastructure with Halter far exceeds water investment without Halter. James says improving the water infrastructure would be a benefit to the farm regardless.

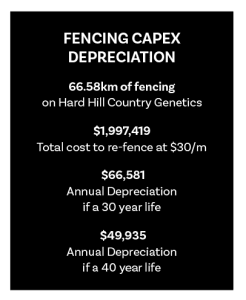

The other big infrastructure cost on any farm is fences. Matauri Angus has 66.6km of largely post and batten fences. Hill country fencing is incredibly expensive at $30-$40 per metre. The cost to replace all the Matauri Angus fences is over $2 million. With a 40 year life that’s $50k pa required to maintain that infrastructure.

“We have been putting in more fences over the last eight years, primarily to improve our pasture utilisation. Now we are considering pulling out some end of life fences rather than replacing them,” says James.

Cost of virtual fencing vs beef returns

The ultimate buck stops with the bank manager looking at the return on investment (ROI) of the capital expenditure (CAPEX) of Halter Base virtual fencing system and the associated running costs.

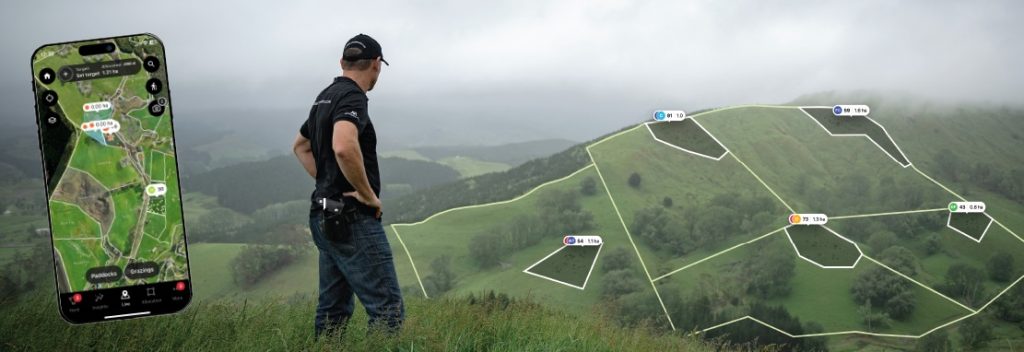

The setup uses solar powered towers that connect to one another automatically and connect to the internet via 4G as long as there is coverage somewhere onfarm. If 4G is unavailable, Starlink can be used with mains power anywhere onfarm.

The number of towers required depends on the terrain of each farm; each tower can reach collars via a more than 3km range, if towers have line of sight to collars. Farmers can use existing lidar maps that contain their geographical info if they have them or can opt to pay for a detailed base map to set up their farm. “The beef system costs half of our full dairy package because it’s simpler than dairy without the animal health monitoring like heat detection. And we have just reduced our dairy virtual fencing entry package by 37% in April too,’ shares Craig.

The Halter Base system costs $96/collar/year on a subscription model, plus the cost of internet.

The Game Changer

A key driver of profit for NZ’s pasture based systems is how much feed we grow and how efficiently we turn that feed into a saleable product. Beef + Lamb New Zealand’s Farming Excellence General Manager Dan Brier, says by using virtual fencing, we will hopefully be able to create better quality feed and more of it.

“I am really excited about the possibilities virtual fencing gives to sheep and beef farmers which should translate to farmers’ bottom lines. Virtual fencing has been on the cards for beef farmers for a number of years now, but to see it in action at James’ property was very impressive,” says Dan.

Dan saw at the recent Beef + Lamb NZ field day how Matauri Farm Manager Travis Pymm is seeing good results and Stock Manager Dan Keay seems to enjoy using Halter in a way that works in harmony with stockmanship and the use of their dogs.

Virtual fencing will also help to better protect soils on North Island hill country prone to erosion. Areas can be excluded from cattle grazing whilst still allowing sheep to graze. The improved productivity per ha also provides the opportunity to retire some less productive or erosion prone areas into trees without reducing the farm’s stocking rate. Options exist around protecting waterways and native biodiversity at a time when new stock exclusion regulations may come

into effect.