The Day of reckoning

No one can deny the numbers of a declining national lamb crop with the over-capacity of processing plants set to collide as the day of reckoning looms closer for New Zealand’s red meat sector. Words Tony Leggett.

The optimists are quick to point to a ‘slowing’ of the sharply declining trend in ewe numbers over successive years and an increase in hogget numbers as a signal that farmer confidence is returning to lamb production.

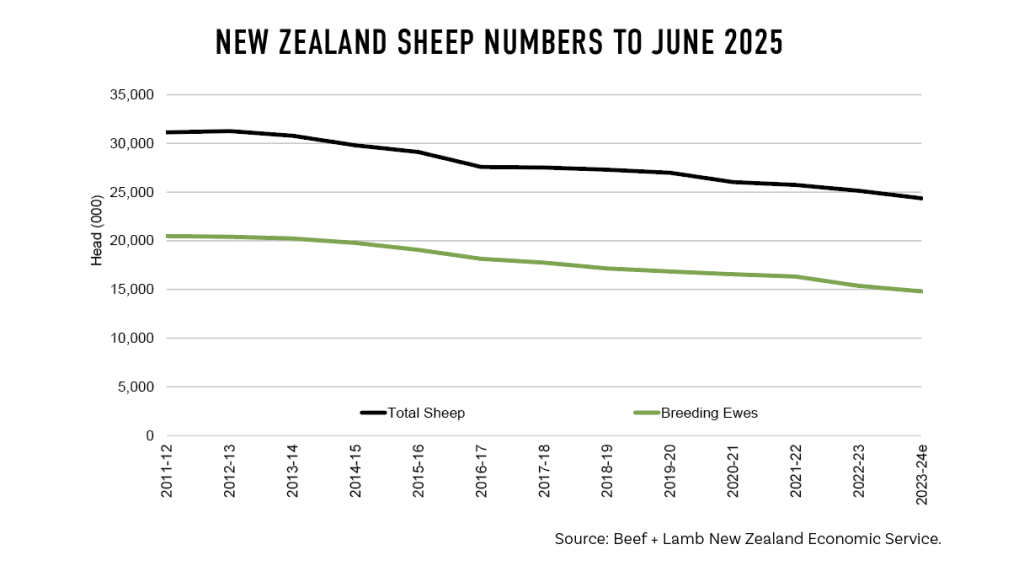

Beef + Lamb New Zealand’s (B+LNZ) Stock Number Survey to 30 June 2025, released in August, confirmed another 1.9% drop in breeding ewe numbers to 14.28 million head (see Figure 1).

But the reality is the 1.7% increase in hogget numbers is driven by trading stock, not ewe hoggets destined to be retained as replacements. The number of hoggets on hand at 30 June was lower in all regions except for the East Coast and Marlborough-Canterbury.

More troubling is B+LNZ’s forecast for the 2025 spring lamb crop.

Although the tally will likely be boosted by more lambs from ewe hoggets and a small increase in the average ewe lambing percentage, it is forecast to reach only 19.29 million head, down nearly 120,000 head on top of a 1.2 million reduction in lambs the previous year.

B+LNZ Chair Kate Acland said farmers had added more beef cattle at the expense of ewes, but the loss of hill-country farms to forestry is creating ongoing concerns for the sector’s long-term viability.

Kate also said the continuing decline in ewes and lamb crop is already having major consequences.

“This (ewe number and lamb crop decline) will only exacerbate already tight supply.”

She has repeatedly called on the government to do more to restrict whole-farm sales for entry into the Emissions Trading Scheme (ETS).

“Our conservative estimate is that 2.6 million stock units have been lost to afforestation since 2017, and afforestation is responsible for 78% of the total reduction in sheep and beef stock numbers since 2017.

In spite of gathering widespread farmer support for an Alliance-Silver Fern Farms merger at the time, it withered from a combination of apathy and lack of support from government.

The government has set a goal of doubling exports by 2034, and sheep and beef farmers will be essential to achieving this goal. Nearly 20% of New Zealand’s export earnings – $10.4 billion in 2024 – come from the red meat sector.

“We can’t double exports if we’ve planted our best farmland in pine trees. We’re calling on the government to do more to restrict whole-farm sales for entry into the ETS.”

Kate’s organisation’s views are echoed by Federated Farmers which says the government’s proposed rules to limit whole-farm conversions to carbon forestry are far too weak to stop the damage being done to rural New Zealand.

“The draft rules have completely missed the mark,” says Marlborough farmer and Federated Farmers forestry spokesperson Richard Dawkins.

“As they’re currently drafted, the proposed regulations will barely make a dent in the number of whole-farm conversions to carbon forestry.”

He says the system allows big urban emitters to buy their way out of reducing emissions while rural communities shoulder the long-term costs and consequences.

“Once you lose a productive sheep and beef farm to carbon forestry, it’s gone for good. Red meat is a cornerstone of our export economy. With strong prices and advances in genetics, pasture management and technology, we should be focused on improving productivity and lifting output – not losing ground.”

So, on one hand, the number of lambs born has already substantially declined, and maybe there are signs of the capital stock ewe flock starting to stabilise. Surely, the substantial improvement in

farm gate returns for sheepmeat this season and steadily increasing crossbred wool prices must help to halt the declining trend in the nation’s capital stock ewe flock.

On the other hand, meat companies face a bigger battle than ever to secure sufficient lambs for processing and exporting to their customers.

While many farmers will relish the thought of meat companies scrapping for their share of a smaller number of lambs, the lower volume of lambs available for slaughter and a flattening of the peak in traditional supply patterns are already significant management headaches for the country’s meat company executives, particularly those with multi-chain sites.

“Consolidation is constantly talked about because there is too much processing capacity in New Zealand, but Alliance Group has taken its fair share.” – Willie Wiese, CEO, Alliance Group

One industry insider said the days of needing multi-chain plants that could be geared up to process the massive summer peak in lamb slaughter are well over. Now, it’s more about agility, supply agreements, and a plant capacity mix dominated by smaller, highly efficient plants with substantially lower overhead costs, that can operate close to 52 weeks a year.

The Meat Industry Excellence (MIE) Group proposed a national moratorium on new plant builds in its plan to merge the two (then) co-operatives Silver Fern Farms and Alliance Group, in 2015.

In spite of gathering widespread farmer support at the time, it withered from a combination of apathy and lack of support from government and the meat processing companies to wrestle with the processing capacity hurdle.

Over-capacity not a shared industry challenge

The challenge of ‘right-sizing’ processing capacity and supply hit home massively for the country’s only farmer co-operative Alliance Group which closed its Smithfield processing site at a cost of almost $50 million in 2024.

Alliance Group Chief Executive Willie Wiese told farmers in August that Irish meat company Dawn Meats had offered to buy 65% of the co-operative for $250 million. Willie explained the need for substantial investment of fresh capital was in spite of a massive restructure of its entire business since he took over, and the company was still too indebted to be able to comfortably trade out of its current position.

When Willie and Board Chair Mark Wynne were questioned about the need for further rationalisation of processing capacity, they were adamant the co-operative had already done its share of plant closures.

Willie says with Smithfield’s closure complete, Alliance Group has a “really well-balanced network” of plants across New Zealand.

“Consolidation is constantly talked about because there is too much processing capacity in New Zealand, but Alliance Group has taken its fair share. We took a hit on your (shareholders’) behalf at Smithfield, at a cost of $48 million, when we had no money. It would not have happened without the support of the company’s bankers who could see the value it offered Alliance Group to do it.

“So, we now have a very good balance between where our processing capacity is located and the stock supply in those regions. Industry consolidation on an industry basis will cost a fortune but it has to be done on terms that create shareholder value,” Willie says.

“I personally don’t like it when people say Alliance Group must consolidate for the good of the industry. My reply is always why should Alliance Group take 100% of the hit? It doesn’t make sense.”

“I personally don’t like it when people say Alliance Group must consolidate for the good of the industry. My reply is always why should Alliance Group take 100% of the hit? It doesn’t make sense.”

However, Mark and Willie both say there are sensible collaborations that could be pursued using models like The Lamb Company which markets lamb into the United States and Canada. Alliance Group has a 43% shareholding along with New Zealand companies ANZCO and Silver Fern Farms, and Australian company WAMCO.

“Are there more opportunities for collaboration? Yes. But as for Alliance Group taking a haircut to consolidate the industry and take out excess capacity, it has to be done on terms that benefit shareholders,” Willie says.

It’s no secret the meat industry is a bloody brutal business. It is dogged by variability in profits which make investing in any innovation difficult and it is heavy in overheads and compliance costs.

Efficiency is everything and that means having a reliable workforce and steady throughput of stock for processing is more challenging than ever. Adding value at scale is risky, because of the massive investment required to grow a new product line from raw material to retail.

Clear vision for a future meat sector

Meat product innovator Daniel Carson has a clear vision of the future for New Zealand’s meat industry. He worked for two years for one of the country’s largest companies before successfully launching his Mīti bars made from young lean beef sourced from the dairy sector.

He says meat companies are too resistant to change and that means they are slower to pick up on opportunities. He fears there are also some questionable operating practices that still exist, even though these are denied by senior management and board members.

“Use of third-party suppliers is a good example of gaps in transparency within some meat companies,” Daniel explains, and says some companies appear blind to the trends in supply and demand.

“For instance, there was just a lot of hope that the decline in ovine (lambs and mutton) especially was not a permanent movement. In some cases, there was so much opportunity to pivot more into beef and invest in new technology in plants when they were profitable just a few years ago.”

He acknowledges the pressure, particularly on both Silver Fern Farms and Alliance Group with farmer shareholders, for companies to have capacity available when droughts force changes in supply patterns.

“I get they are farmer co-ops and it’s a different model of ownership. But other businesses can’t operate like that.

“If you look at the privately-owned companies like ANZCO or Greenlea for example, I guarantee you they wouldn’t have many suppliers in the bottom 50% of farmers.That’s because they attract the better farmers because there’s a lot of contracts, there’s a lot of performance specification required, and there’s a lot of planning in their supply.

“That is why you don’t see those private companies chasing, chasing, chasing, because they contract most of their supply so it is reasonably predictable and people get rewarded for that.”

Daniel says the farmers supplying those contracts know they cannot renege on their commitment, even if there is a drought, and they will prioritise the feeding of those animals so they supply on the dates required to get the premiums.

“Whereas the co-ops don’t create the same farmer behaviour that will improve the whole industry. So, if farmers have more feed available, they put more weight on animals. That is fine, but that screws it for everybody else and screws it for the meat company.”

In spite of his plan to scale up his Mīti business to fill a massive global demand for nutrient-dense, low carbon footprint foods, he’s hamstrung by a lack of toll processing and packing availability.

Daniel’s vision is for a future meat industry where the production system itself is the brand – emphasising pasture-raised, low carbon, farmer-centric and science-backed principles, with carbon and nutrition as new key metrics.

Creating red meat innovation spaces in New Zealand would also be helpful for start-ups like Mīti.

His company has invested $500,000 on science to develop its Mīti product, and proved the entire system has the lowest carbon footprint of any beef product analysed.

“We’re obviously leaning into red meat as functional nutrition, combining it with other unique New Zealand ingredients, playing into this natural image we have globally.

“The co-ops don’t create the same farmer behaviour (as privately owned processors) that will improve the whole industry.” – Daniel Carson, Founder, Mīti

“If you think of all these different fruits, kiwifruit powder, cherry powders, or muscle extract, you can combine all these things together to get very specific outcomes for nutrition in elderly populations, youth nutrition, whatever.

“Meat’s not playing into that. We still think in terms of a patty!”

Daniel believes the meat industry’s resistance to innovation stems from a desire by senior executives to control the entire process and a belief they know best, so innovative ideas from external parties are blocked.

“New Zealand Inc actually has something unique here that we could build a brand around. Essentially it just requires thinking the same as our forefathers did with lamb. You know, until there was refrigerated shipping, lamb wasn’t a thing.”

Building his own fully vertically integrated processing and packing plant is the only option to scale up and tap into the export market.