Succession: Time for action

There is no off-the-shelf succession plan. Every business and every family is different, Peter Flannery writes.

There is no off-the-shelf succession plan. Every business and every family is different, Peter Flannery writes.

Previously I raised the question of how to transfer ownership of the family farm to the next generation. I discussed the actual transfer of land is not the difficult part. It is making the transfer of ownership work, with regards to ensuring financial sustainability while treating all family members fairly.

To that end I made the point that it is what happens before and after the transfer of ownership that will determine the success or otherwise of a succession plan.

Before any transfer of ownership can occur, you first need to build a strong business to help provide you with options, followed by having some potentially courageous conversations with the family to help define what is fair for your family’s situation.

Every business is different, and every family is different. So there is no “off the shelf” succession plan. Your plan needs to be tailor-made for your particular family, and this cannot occur without family wide consultation.

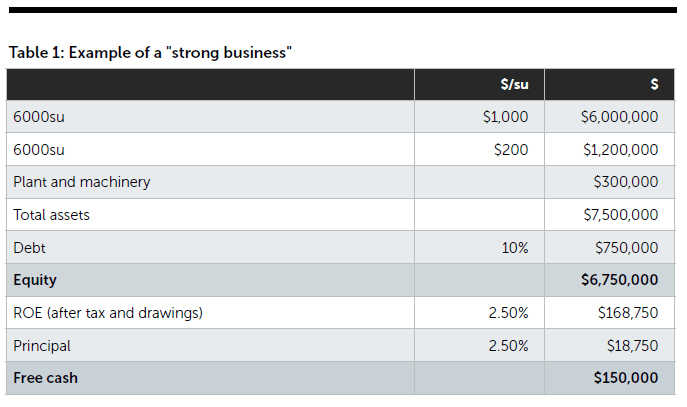

In my previous column I gave the example of a family business of 6000 stock units as follows:

Total assets of $7.5million with debt at 10% of assets giving equity of $6.5m dropping out $150,000 of free cash after wages of management (drawings), tax and principal. In the example, as well as the parents, there were four children. So let’s give them some names. First, Fred who has been home on the farm for five years. Florence, a nurse, married to a successful surgeon. Sam has strong farming aspirations of her own. Finally Bob who is enjoying an extended OE with no real plans while he tries to “find himself”.

Meanwhile, mum and dad want to retire to their yet-to-be-bought dream home overlooking the beach or lake within the next five years.

Putting the plan into action

How can a successful succession plan be put into action? While the business in its current state is strong, there will be financial constraints.

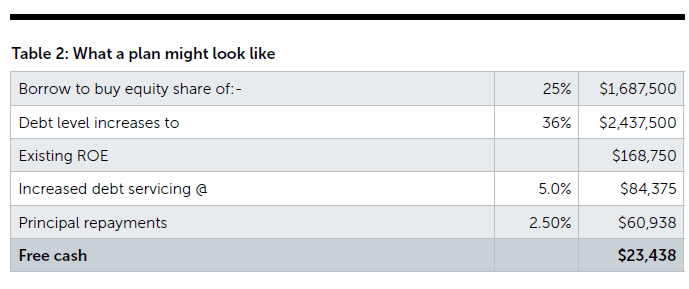

If mum and dad were to sell 25% of the business to Fred, this would provide the parents with capital of $1.7m, which they would remove from the business to buy their dream home with maybe a minimal amount of cash left over. Where does Fred get his $1.7m from? Chances are that if he has been living and working on the farm for the past five years, he is not going to have a lot of capital of his own. So he will have to borrow most of the capital from a bank, which will only be lent against the assets and cashflow of the farm.

Borrowing another $1.7m of capital is going to use up most of the “borrowing capability” and free cash of the business. Table 2 shows in this example, free cash reduces to $23,000 after repaying principal.

It works on paper, in that it gets Fred in the door to ownership, and it helps partly settle mum and dad into retirement. However, it doesn’t address the parent’s access to retirement income and future lump sum capital requirements. Nor does it help Sam with her farming aspirations or provide anything for Florence and Bob. So it is a plan that is unlikely to work.

Need for courageous discussion

So if that option is not going to work, what is the alternative? First, this demonstrates the need to have those potentially courageous conversations. The success or otherwise is going to depend on the family’s attitude.

How do mum and dad view their capital? Do they have the view that it is theirs, and must be protected at all costs, and keep it close to their chests, or do they hold the view that the capital is there to be used to benefit everyone? What are the siblings’ attitudes? Where do they sit on the continuum of self before others or others before self?

How important is it to the family that the farm stays within the family?

If it is a non-negotiable, then the successor and in this example potentially two successors, need to be treated preferentially. How fair is that? Again, that is for the family to decide.

If Florence and Bob both have very mature attitudes and would rather see the farm stay in the family, and give both Fred and Sam their farming opportunities, then there is every chance the farm can be retained within the family, which we have established is a non-negotiable. However, if Florence and Bob both expect a significant capital payout, then the ability to keep the farm within the family starts to become less certain and is therefore no longer non-negotiable.

What this example shows is that a seemingly strong business is going to have some severe financial constraints when it comes to succession planning. It is a strong enough business to support mum and dad’s needs by providing good levels of free cash. However, once the needs of the next generation are taken into account, suddenly the business is not strong enough.

If no one is interested in the farm, the solution is simple. Mum and dad sell up when they are good and ready, distribute a bit of capital now, if they wish, and settle into a well-funded and financially secure retirement. However, that is not the case in this example, with potentially two successors and two others in very different financial situations.

We are assuming of course that Florence and Bob need to be bought out of the business. That seems to be the most common path. That is, one or maybe two end up with the farm while the remaining siblings get a cash payout at some time in the future.

However, it doesn’t have to be this way. Again, if everyone has a mature attitude and an “abundant mentality” there are other options. An abundant mentality means “there is plenty in this business for everyone, and if we work together we can all achieve more than just doing our own thing”.

This is called being interdependent. Let’s work together so we can all benefit. Its great in theory, and there are wonderful examples of it succeeding. But humans being humans, it is not easy to achieve.

- Peter Flannery is an Invercargill-based Agri Business Consultant, peter@farm-plan.co.nz