Succession is a marathon, not a sprint

By Kate Taylor

There is no one-size-fits-all solution for farm succession but it’s important to ask the right questions at the start of the process, farm business consultant Mandi McLeod says.

There is no one-size-fits-all solution for farm succession but it’s important to ask the right questions at the start of the process, farm business consultant Mandi McLeod says.

Many people start succession planning with someone with the hard skills of accounting or law, but they’re talking about structure, and not genuinely figuring out what the family wants, she says.

“People shouldn’t underestimate the emotional journey they will go on, but at the same time, they shouldn’t be afraid of it.

“The worst thing we can have is people going in with the best of intentions and failing because they don’t have the soft skills to deal with the social issues. None of it works unless you understand the family dynamics before even looking at solutions. If you haven’t dealt with individual family communication, it doesn’t matter how good the accounting or legal solutions are; they won’t keep your family intact.”

McLeod set up her own consultancy, Systems Insight Ltd, in 2002, which included work on farm/family business strategy, inter-generational transfer and governance coaching. Her 2009 Nuffield scholarship also concentrated on those issues.

“I’d realised two things: one was that succession was focused on asset transfer, pretty much at time of death, and there wasn’t a focus on transitioning management skills with succession. All the research was non-agricultural, non-rural; farm businesses had quite different needs that didn’t fit the box. When you’re on a farm, you don’t get to drive home after work. If you’re in another business and you employ family, they’re generally not living on the work site. You’re not looking into each other’s lives.”

She says there can be pressure on people who aren’t ready to abdicate power or control, and nothing will work until that happens.

“People who start successful family businesses are entrepreneurs and they get there because of power and control, so there’s a sense of loss of identity in giving that up. Then we have a generation of people who haven’t learnt patience. They want it now. But it takes time to work out what all family members want, and need, and expect from the family business.”

Both generations must be ready for the change.

“Mums and dads shouldn’t have to compromise their lifestyle for the second generation coming in, just to give them an opportunity. They have to be ready for a partner in the business and the successor has to have the necessary management skills or willingness to learn.”

McLeod bought into her parents’ 300-cow dairy farm in Waikato, but it was sold six years ago when she realised she couldn’t afford to expand or buy out her four siblings.

“I wanted my parents to have the life they earned, and it also gave them the opportunity to help other family members. We kept a third of the land, where they still live.”

Before that, McLeod says she had the triple whammy of living and breathing her own succession journey, researching with international colleagues to translate non-farming succession stories into farming, while also working directly with farm businesses.

“It made me a bit unique, because my international colleagues were either running workshops or working in the academic field, they weren’t actually at the coalface of sitting with families and sometimes working through generations of trauma.”

Emphasis on the word, trauma.

“There are a number of family businesses where someone got the farm from gender or birthright. There were families where previous generations had not dealt well with succession so they had generations of family members not speaking to each other. I have knowledge of successors who had suicided or had breakdowns because they were put in positions of responsibility they were not equipped to deal with.”

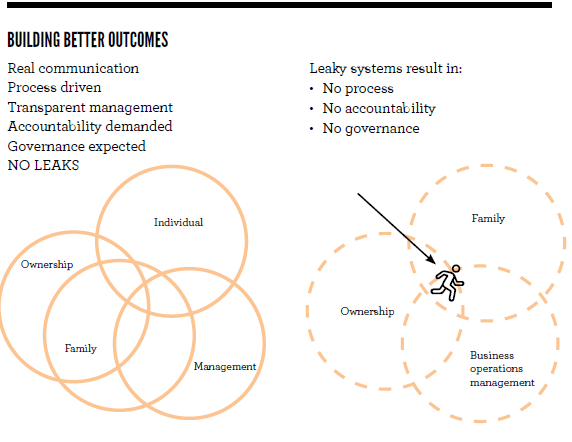

She uses a diagram with interlocking circles – family, management and ownership – to show the complexity of a family farming business. Traditionally they were viewed as discreet silos, but the greatest challenge lies when the three circles intercept, i.e. family members involved in management and ownership.

“Asking who needs to be where and what needs to be done to shift people through the different circles, while also acknowledging the emotional content. In a successful business, the lines on those circles are thick, but in a leaky circle, there’s no governance, no accountability.

“People need to ask, ‘Is that someone I would employ if they weren’t my son or daughter?’ or for the younger generations, ‘Would I work for them if they weren’t my parents?’ In farming, families go into business together simply because they share DNA.”

People need process and a clear structure for introducing family members to a farming business, but she says many still want the end result without doing the work in the middle of the circles, which is communication.

“Genuinely understanding what family members want from the process; those expectations, more often than not, will derail the process if they haven’t been met, managed or mitigated. The equation should be for fair, rather than equal, and everyone being on the same page. Fair is sometimes equal but equal is very seldom fair.”