Sheep not guilty over N leaching

Trials at Massey University have proven sheep to be low-leaching in nitrates, Joanna Grigg reports.

Trials at Massey University have proven sheep to be low-leaching in nitrates, Joanna Grigg reports.

Back in 2019, Essential Freshwater legislation was looking to grandparent sheep and beef farm nitrate levels. This would have locked farms into existing stocking rates and environmental discharges.

Beef + Lamb NZ chairman Andrew Morrison said at the time that New Zealand sheep and beef farming systems had low nitrogen leaching rates. There was plenty of room to increase allowances.

“Catchments where sheep and beef farms are the predominant farming system, nitrogen levels are not an issue.”

He was right, Massey University School of Agriculture and Environment senior lecturer James Milner says, but back in 2019, there was a gap in the research as to proven levels of nitrate leaching under intensive sheep farming. This was especially on different forages and we needed research to prove it.

“There was some evidence to support sheep being low leaching, but it wasn’t conclusive evidence.”

This was set against a backdrop of legislation changes. Councils like Environment Canterbury started rolling out rules around nitrate leaching, self-described as “some of the strictest farming rules in the country”.

More data was needed to prove sheep sustainability and inform policy. Millner says the only sheep system leachate data on hand were measurements done 20 years ago, using lysimeters, which have limitations.

Dairy was well ahead. Massey had been testing dairy system leachate for several years at their Number Four farm. Over the road from Number Four, were drainage plots on the university’s Keeble’s farm. These plots are high-tech and expensive hydrologically isolated mole and pipe drainage systems, Milner says. These 40×20 metre plots capture all drainage.

“They give really good data.”

Through funding from the L.A. Alexander Trust, the C. Alma Baker Trust and Massey University, sheep were run across these plots, over a three-year trial. PhD student Sarmini Maheswaran, from Sri Lanka, collected and analysed the leachate data. The results were published in May.

The trial was set-up to get insight into the effects of different plant types sheep eat. The four grazing treatments were perennial ryegrass/white clover, plantain/white clover, Italian ryegrass/white clover with brassica, and a crop system; Turnips year one, swedes year two and kale year three. The plots were replicated.

The reasons behind the selection were to test whether plantain could reduce urine nitrogen (N) concentration in sheep – something it’s known to do in cattle. Italian ryegrass was included as its winter activity means it can suck up soil N when leaching risk is high. The brassica crop treatment was included because it is an important supplementary feed in sheep systems.

“It is often harder to get funding for sheep research, than dairy, as there is less political or environmental pressure,” Millner says.

“But it is important to know the influence forage may have on leaching in sheep systems, to inform farmer decision making.”

The next leachate trial at Massey is comparing mixed sheep and cattle systems, on a range of forages. Yearling cattle will run alongside sheep at 14 stock units/hectare.

Sheep give nitrate advantage

Intensive sheep at the same stocking rate equivalent to cattle, means more bladders per hectare. But these bladders are smaller. This means urine is spread more evenly across a block, resulting in less nitrate leaching potential.

While this makes logical sense, the finer points of sheep grazing and forage types, on leachate levels, are less understood.

Results from a three-year Massey University trial on nitrate leaching under sheep, have revealed that forage type does affect leaching rates. While the nitrate leached annually under each forage was generally low, it did range.

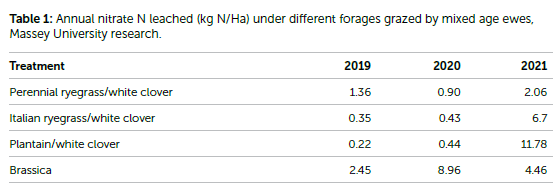

The annual pattern for the three permanent forages was similar, with the highest N losses occurring in 2021 for all forages apart from brassica. For the first two years of the study the brassica crop produced the highest leached N totals.

The brassica plots were intensively grazed during winter, followed by a period where the soil was left bare until soil conditions allowed replanting. This was typically spring. This demonstrates the potential for higher losses of nitrate, resulting from urine patches in the absence of vegetation and plant uptake. Recent research has shown N leaching losses from forage crops grazed by dairy cows during winter could be more than twice those under grazed pasture.

The drainage plots were grazed based on cumulation of forage. Ewes were transitioned from ryegrass/white clover prior to being grazed on the drainage plots.

In 2021, kale was used as the brassica crop and the plots grazed between June and July. Nitrate leaching under kale was low compared to that observed under swedes in 2020 (8.96kg N/ha). This is probably due to available soil N being low, as the kale crop was the third successive crop in this treatment. To back up this conclusion, the leaf N content of the kale was about half that of the previously grazed turnips and swedes.

The stage and age of the forage/pastures also affected leaching rates.

For example, when plantain was thick in the sward at the start of the trial in 2019, leachate was only 0.22kg/ha. By the end of the trial, weeds had invaded and plantain content lowered, so the block was sprayed and drilled. At this point the plantain/white clover plot in 2021 produced leachate of 11.78kg/ha. Killing off the vegetation and resowing on these plots produced a spike in leached nitrate but really was an aberration.

Milner describes the peak rate (see Table 1) as not high, especially compared to the dairy system rate of 30-40kg/ha.

“It’s not even close.”

The first two years of the study indicate that swards with plantain are effective at reducing N leaching, under sheep grazing. The benefits of plantain are well described. Sheep produce more urine when grazing plantain but the concentration of urea in the urine is less, so it is more likely that the sward will be able to utilise it all, Milner says.

Urine collected from the ewes in this study, revealed that urea concentration from ewes grazing the plantain sward was significantly lower than the other treatments.

The performance of the sheep used in the study was monitored (liveweight, lambing percent and lamb weight), as well as seasonal urine urea content.

Results help guide farmers

Knowing intensive sheep systems leach only about one-quarter of nitrates of intensive dairy systems, and that sheep have reduced leaching on plantain, are helpful messages for farmers.

“These sorts of findings can inform farmer decision making,” Milner says.

“It should also inform policy makers as clearly there is an argument for sheep to remain in sensitive catchments, because of the reduced leaching losses.”

The results also suggest opportunities to partly or fully replace cattle systems with intensive sheep, to help meet regulated annual limits on leaching per hectare. While Milner doesn’t think it’s feasible for dairy farmers to get into lamb finishing on any scale, a small number do integrate in sheep, especially on steeper areas.

Milner says tweaking sheep/cattle ratios, as well as changing grazing forage types and rotation lengths, are other possibilities. This study suggests that, in sensitive catchments, the use of forage crops (such as swedes and kale) to feed sheep rather than cattle over the winter period may be a useful strategy to reduce N losses through leaching. There is good evidence that plantain can be used to reduce N leaching under sheep grazing. Italian ryegrass may also be useful to soak up nitrate, a function of its winter activity.

The research has also thrown up the question as to whether sheep have genetic differences in their ability to metabolise nitrogen. The urea content in sheep urine was measured, as part of the trial.

“They probably do, but it’s speculative at this stage and a long way from being verified.”

He says more research is also needed measuring leaching given variations in rainfall and temperatures.

Why is nitrate an issue?

Nitrogen cycling in grazing systems is influenced by diet and the partitioning of ingested N in grazing animals. Between 75-95% of N ingested is excreted, with about 70% of that being urea (urine).

Nitrate (NO3-) is the most common form of N leaching in drainage water. This is largely due to its negative charge, which means it is repelled by cation exchange sites in the soil, rather than being sorbed (taken up, held). When water percolates through soil after rain or irrigation, it carries nitrate with it.

In contrast, the other important source of N in soil, ammonium (NH4+), does not generally move much through the soil. This is because it is sorbed at cation exchange sites.