Shed or Shear?

Kate Kellick’s Kellogg report calls for a shift towards shedding sheep as a solution to the pressing issues facing New Zealand’s sheep farming industry. Words Sarah Perriam-Lampp.

The Kellick family have farmed at Mangamahu near Whanganui for over 150 years. One of the biggest drivers for the Kellicks to take the first steps in shedding sheep was a father adamant to find sheep farming for the next generation. Fifteen years on, Kate Kellick has been instrumental in moving the Tokorangi Farm’s entire flock to shedding sheep.

The debate over shedding versus woolly sheep has become increasingly prominent, as farmers confront a complex blend of generational farming practices and a rapidly changing global economic environment. Yet, this crisis has forced farmers to innovate and diversify, including the Kellick family when Kate’s father passed away.

“Dad was a shearer and had a bad back, and along with the wool prices being crap he started to dabble trying a few different breeds and he bought a couple of shedding sheep,” shares Kate. “After Dad died I came back to the farm with my first baby, and was like, Jeepers, how am I actually going to do this?”

Her family’s transition from woolly sheep to shedding sheep took about five to six years and they have now not shorn for seven years. She explains her children have never experienced shearing – a farming activity that was naturally part of Kate’s upbringing.

The Kellicks now sell 40–50 rams per year at their esheep stud with their 2024 top ram fetching $8,000, with the average price settling at $3,500. “That’s apparently topped the average ram price in New Zealand,” says Kate.

“I’ve actually recently just employed a stock manager full-time, because the stud went from no workload to being quite a massive workload, so we’ve had to employ someone to help with all of that side of things.”

Kate undertook a 2024 Kellogg report, Shed or Shear? Changing the path of New Zealand sheep farming, which provides a comprehensive look at the economic and environmental benefits of transitioning to shedding sheep, positioning them as a practical solution to many of the industry’s current challenges.

She touches on the history that sheep originally domesticated from the wild Mouflon did not naturally grow wool. The domestication process, which began over 12,000 years ago in the Middle East, was driven by selective breeding sheep that naturally produced more fleece. Wool then went on to replace leather as the primary material for clothing, driven largely by its superior insulating properties. Over centuries, this selective breeding led to the development of sheep breeds with increasingly dense and soft wool, which would become the backbone of the wool industry.

Cost analysis

Cost analysis

One of the major findings is the clear financial and environmental advantage of transitioning to shedding sheep.

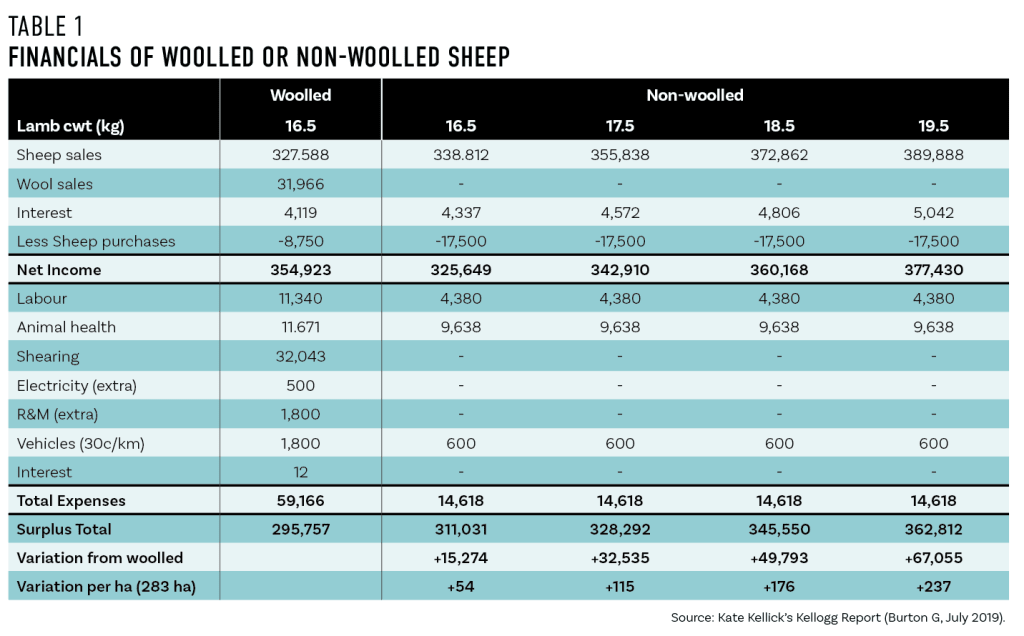

In Kate’s report she provides a financial comparison of non-woolled with woolled sheep farming profit and loss completed by Grant and Sandra McMillan on their shedding sheep property ‘Ongarue’.

The comparison concludes a $15,000 increase in farming surplus where non-woolled and woolled lambs are the same weight at slaughter. This surplus increases substantially up to $67,000 where the shedding lambs are achieving 1.5–2kg heavier carcase weights.

These breeds offer lower labour costs, improved animal health and welfare, and enhanced productivity. The shift also leads to reduced health and safety risks for farmers, as well as less environmental impact due to the elimination of wool-related activities like shearing, crutching, and dipping.

“Regionally and even for remote properties, the cost of transport and shearing gangs travelling, not staying on farm any more – it all adds up.”

Kate explains that shedding sheep are less prone to issues like flystrike and have better parasite resistance, reducing the cost and labour of animal health treatments.

Yet despite these benefits, Kate’s report highlights that a resistance to change remains one of the largest barriers to widespread adoption of shedding breeds. Many farmers are hesitant to abandon wool production due to traditional mindsets and the hope that wool prices will rebound.

Kate does say there are challenges that farmers must consider when transitioning to shedding breeds such as a high initial investment, and the concern about losing genetic progress in their existing flocks. She recommends building stronger networks within the shedding sheep community, investing in genetic research, and setting clear genetic goals for your flock.

“I started doing a shedding sheep discussion group with Trevor Cook up in the King Country as there seems to be quite a lot of contamination in their wool – its regional pockets due to climate and drench resistance that shedding sheep is taking off.”

The transition from wool to shedding breeds typically takes between 3–5 years with full shedding achieved in 12–15 years when grading up from existing wool breeds.

However, Kate stresses that for shedding sheep to succeed, a complete shift in the industry’s mindset is necessary – starting with reducing supply chain costs.

“There is always a place for niche wool markets, where scarcity could drive up value.”

Kate estimates following her research that standard strong wool would need to be at $10–$11/kg to remain viable. She sees a tipping point on the horizon, as more farmers make the switch and wool infrastructure faces decline.

“I think the shedding sheep is probably going to be the thing that just pushes that last domino with no return over – the mass exodus from wool sheep.”

Kate’s top benefits of shedding sheep

- Reduced shearing, crutching, and dipping costs.

- Reduced feed costs – shedding sheep uses less energy for wool production, leading to lower feed requirements and the ability to raise stock numbers.

- Reduced labour – the report found that farmers managing shedding sheep spent 61% fewer hours on sheep handling, compared to wool breeds.

- Reduced stress on sheep, particularly in hot or unsettled weather.

- Reduced risk of flystrike.

- Enhanced farmer wellbeing. One farmer shared, “Never been so happy with sheep … Wiltshires do not require countless hours of unrewarded time.”

- Reduced use of chemicals, animal health products.